April 2012

Monthly Archive

Fri 6 Apr 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

When stuck for something to write about, browse the Web. I did that recently and discovered on the Bernard Herrmann Society website an excellent item to kick off this column with, an interview with composer Fred Steiner (1923-2011), whose main claim to fame for mystery lovers is that he wrote the theme for the Perry Mason TV series, which you may listen to here.

Here, laboriously transcribed by my own fingers, is what he had to say on that subject in the 2003 interview:

“A lot of people have asked me about it. ‘How did you come up with that theme?’ I really don’t know. I found some old sketches for the Perry Mason theme, some old pencil sketches, and they have no resemblance to what I finally came up with. So it’s a complete mystery to me.

“I think the first time we recorded it, of all things, was in Mexico City, because of union complications. The original title was ‘Park Avenue Beat.’ And the reason for that was, I conceived of Perry Mason as this very sophisticated lawyer, eats at the best restaurants, tailor-made suits and so on, and at the same time he’s mixed in with these underworld bad guys, murder and crime.

“The underlying beat is R&B, rhythm and blues, and for the crazy reason that in those days, and even to this day, jazz or R&B is always associated with crime. You look at those old film noir pictures, they’ve always got jazz going for some reason or other. It’s like every time you see a Nazi they play Wagner.

“[The theme is] a piece of symphonic R&B. That’s why it’s called ‘Park Avenue Beat,’ but since then it’s been known as the Perry Mason theme… It’s always been used. It’s gone through several changes depending on the timing, because they would change the main titles year in and year out.â€

During the late Fifties and early Sixties when Perry Mason was in prime time, the head of the CBS west coast music department was Lud Gluskin (1898-1989) and the best-known composer working for him of course was Herrmann (1911-1975), whose ominous music was heard frequently in the episodes from the first two years of the series.

Steiner went on to tell of another Herrmann-Mason connection:

“I heard a story from Bernard Herrmann that at one point somebody said that they were tired of the theme and could we get something else. So Lud Gluskin got Benny to write the theme, but then the story is that Benny Herrmann said ‘What do you want me to write a theme for? Steiner’s is perfectly good.’ So they relented, went back to my theme. They never changed it.â€

Listening to Steiner’s words as Perry Mason would listen to the testimony of a witness against his client, do you detect the ambiguity I do? If Steiner were on the stand and you were cross-examining him, wouldn’t you ask the same question I would?

“Mr. Steiner, do you know whether Herrmann actually wrote a new theme for the series before he persuaded his bosses that they didn’t need one?â€

Steiner died last June so the answer may never be known. But if he had replied that Herrmann did indeed write such a theme, wouldn’t you love to knew where it is? Or better still, to hear it?

At least we can see Steiner and hear the interview on YouTube.

From the Fifties let’s retreat to 1928, the year Fred Dannay and his cousin Manny Lee were writing The Roman Hat Mystery and creating Ellery Queen. How did they come up with the name?

It’s been known for decades that Ellery was the name of Fred’s closest friend when he was growing up in Elmira, New York. How they settled on Queen was explained in an audio recording played at the Columbia University’s Queen centennial conference in 2005.

The speaker is Patricia Lee Caldwell (1928- ), Manny’s oldest daughter, who had the story from her mother, Manny’s first wife, Betty Miller (1909-1974). Manny had married her in 1927 when she was 18 years old and he was 22. They were living in an apartment on Ocean Avenue in Brooklyn when their daughter was born.

“My mother told me that the families used to get together a lot over the weekends… She said that one weekend cousin Fred and Manny were playing cards… I think she said it was bridge… This was … around the time when they were writing

The Roman Hat Mystery, and they were trying to think of a name for their character and for their pseudonym.

“They had already decided on Ellery … but they hadn’t decided on a last name. Well, they were playing cards, and my mother said that they suddenly looked at the picture cards and they said: ‘Yeah, wait, the picture cards. Maybe this will give us something.’

“And they suddenly decided it would be Ellery King … but it didn’t seem quite right, and so they diddled around with it a little and they said: ‘No, Queen. Queen!’ The letter Q is extremely unusual in the English alphabet, and it would be much more memorable.â€

And which of us shall say that it wasn’t?

Now let’s jump forward to a time when Ellery Queen was a household word, specifically to the fall of 1946 when the first volume of The Queen’s Awards brought together the prizewinners in the first annual story contest that Fred Dannay conducted for Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine.

Among the winners of the six second prizes — $250 apiece, which was a nice chunk of money in those days — was William Faulkner for “An Error in Chemistry†(EQMM, June 1946), the future Nobel laureate’s only original contribution to the magazine. (The two other Faulkner stories Fred bought were reprints.)

From various Faulkner biographies we learn that he lost no time deriding both the magazine and the prize. “What a commentary,†he wrote his agent. “In France I am the father of a literary movement. In Europe I am considered the best modern American and among the first of all writers. In America I eke out a hack’s motion picture wages by winning second prize in a manufactured mystery story contest.â€

A true Southern gentleman, yes?

Fri 6 Apr 2012

IT’S ABOUT CRIME, by Marvin Lachman

FREDRICK D. HUEBNER – Judgment by Fire. Fawcett Gold Medal, paperback original, 1988.

I was not surprised after reading Fredrick D. Huebner’s Judgment by Fire, a paperback original from Gold Medal, to learn that the author is an attorney.

Even if my son weren’t a lawyer, I would disagree with the character in Shakespeare who said, “First, kill all the lawyers.” Writers in that profession, e.g., Huebner, Healey, Nevins, and Hensley are too good at integrating the law into their mystery plots.

At times, Huebner’s well-described courtroom scenes (even the motions made are suspenseful) threaten to overwhelm his rather meager plot. The book reaches its peak midway with a murder-arson trial and then is anticlimactic.

Still, on balance, this is a worthwhile mystery with a good description of the Seattle area, especially its perennial rain.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 11, No. 1, Winter 1989.

The Matt Riordan mystery series —

1. The Joshua Sequence (1986)

2. The Black Rose (1987)

3. Judgement By Fire (1988)

4. Picture Postcard (1990)

5. Methods of Execution (1994)

Fri 6 Apr 2012

Posted by Steve under

Authors ,

Reviews1 Comment

THE ARMCHAIR REVIEWER

Allen J. Hubin

JOHN M. FORD – The Scholars of Night. Tor, hardcover, 1988; paperback, 1989.

John M. Ford, author of an award-winning fantasy novel, enters the espionage lists with The Scholars of Night. Nicholas Hansard is hardly anything like a spy. He’s an academic, a historian, a man of no violent urges and no particular physical prowess.

He’s also a member of Raphael’s Washington think tank, and his best friend is Allan Berenson, master of board games of politics and war. And dead. And, apparently, a traitor.

A recently uncovered four-hundred-year-old play, possibly by Christopher Marlowe, has something to do with all this. Hansard, in sorrow and rage, resigns from the tank. But Raphael asks him first to go to England, have a look at the play, give his opinion on historicity.

He agrees. So easy to get lured into the world of death and double-dealing. Quite an artistic job we have here by Ford, crafty and complex … and perhaps a bit too fuzzy around the edges.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 11, No. 1, Winter 1989.

Bio-Bibliographic Notes: This is the only work of crime or espionage fiction by the witty and multi-talented John M. Ford included in Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, but he had a long list of science fiction and fantasy novels to his credit when he died in 2006. He left us far too early; he was only 49 at the time of his passing. For more information, check out his Wikipedia page here.

Fri 6 Apr 2012

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

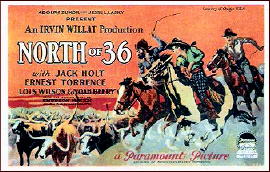

NORTH OF 36. Paramount Pictures, 1924. Jack Holt, Ernest Torrance, Lois Wilson, Noah Beery, David Dunbar, Stephen Carr. Based on the novel by Emerson Hough. Director: Irvin Willat. Shown at Cinevent 35, Columbus OH, May 2003.

Lois Wilson plays Taisie Lockheart, a Texas rancher who needs to get her herd of cattle to Abilene and across “a thousand miles of Indian territory.” Noah Berry, the villainous Texas State Treasurer (some things never change, I guess) Sim Rudabaugh, scheming to take control of her land by any means necessary, tracks the cattle drive with a crew of ruffians among whom is good guy Jack Holt aiming to thwart Rudabaugh’s plan.

This was conceived as a sequel to The Covered Wagon and was to be directed by James Cruze, but a cut in the budget lost the company the director and its grandiose plans for another epic of the West.

However, they were able to engage the last remaining herd of longhorn cattle for the drive and the excitement of the drive and the work of an excellent cast more than makes up for any budget deficiencies.

The punishment meted out to Rudabaugh by the Indians he’s wronged is a truly horrific moment in film vengeance, and the audience responded with cheers and applause. They don’t make ’em like this anymore. And they should.

Thu 5 Apr 2012

A TV Series Review by Michael Shonk

HONG KONG. ABC / 20th Century Fox. 1960-61, 26 episodes at 60 minutes each. Cast: Rod Taylor as Glenn Evans, Lloyd Bochner as Chief Inspector Neil Campbell, Gerald Jann as Ling. Created by Robert Buckner. Executive Producer: William Self.

The series currently is not available on DVD. I have viewed six episodes of the series. More are available in the collector-to-collector market.

Hong Kong is another unjustly forgotten treasure from television’s past. The series, with its black and white film and quality talent behind the camera, created an atmosphere reminiscent of film noir.

Among the writers were Jonathan Latimer (novel: Headed for a Hearse; film: The Glass Key, 1942; TV’s Perry Mason) and Sam Ross (Naked City). Herbert Hirschman (Perry Mason) produced many of the episodes.

But it is the list of directors that is truly impressive, Walter Doniger (Bat Masterson), Paul Henreid (Alfred Hitchcock Presents), Ida Lupino (Have Gun Will Travel; The Hitch-Hiker, 1953), Fletcher Markle (Jigsaw, 1949), and Stuart Rosenberg (Cool Hand Luke, 1967).

The cast performed well, with Rod Taylor (Time Machine, 1960) starring in his first TV series as Glenn Davis, hardboiled reporter and ladies man. Lloyd Bochner (Twilight Zone) was perfect in his breakout role as the very British Neil Campbell.

A hidden treasure, all by itself, was the movie quality soundtrack done by future Oscar winner Lionel Newman. Take a listen.

Sadly, ABC was determined to waste the quality series on a suicide mission against NBC’s ratings hit Wagon Train. The Indians had a better chance. However, ABC, 20th Century Fox and powerful sponsor Kaiser Industries (who also sponsored Maverick) strongly supported this series.

In Broadcasting (4/11/60) ABC President Treyz claimed Hong Kong was the “most expensive weekly one-hour series in the history of ABC, and I believe, in the history of the television medium.â€

Hong Kong was about the adventures of World Wide News’ foreign correspondent, Glenn Davis. Glenn drove a great car, a white convertible. He was a close friend of British Chief Inspector Neil Campbell. In early episodes Glenn hung out at Tully’s, a restaurant run by Tully, a shady character with helpful contacts (Jack Kruschen).

The ratings for the series were disappointing from the very beginning. Hong Kong‘s premiere episode (9/28/60) finished third in its time slot to NBC’S Wagon Train and CBS’ second place Aquanauts (later called Malibu Run). (Broadcasting, 10/3/60)

Despite rumors Hong Kong was to be cancelled at mid-season, sponsor Kaiser Industries continued to support the series after some changes were made by the 20th Century Fox’s new Vice President in charge of TV Production, Roy Huggins (Maverick). (Broadcasting, 12/12/60)

Glenn found a new place to hangout. Tully’s was replaced by the Golden Dagger, a supper club run by Ching Mei (Mai Tai Sing). The Golden Dagger featured popular singers (including Julie London, Anne Francis) for the occasional love interest of the week and added more music to the series.

What didn’t change were the fistfights, mysteries, and romance to appeal to all types of viewers, but who continued to watch Wagon Train.

ABC tried Hong Kong at 10pm (preempting Naked City) on January 25, 1961. The ratings were a success with a 42.1 share but lower than Naked City‘s usual 43 share. And the episodes at 7:30pm continued to fail in the ratings against the competition. (Broadcasting 1/30/61)

Thousands protested when the series was cancelled. Hong Kong was a success in syndication. There is a fan site for Rod Taylor that has some more about the series and its cancellation.

For those not wanting to bother with the link, the website’s highlight is a copy of a January 1962 gossipy styled article from newspaper syndicate NEA. It claimed the studio cancelled the series when “a big talent agency†that had brought the series to Fox raised their fees beyond what Fox was willing to pay. The “sponsor†was upset so Fox offered Rod Taylor a role in Follow the Sun. Taylor by then was in Italy shooting a movie for MGM.

The article also mentions the plans for a sequel called Dateline: San Francisco. In the pilot, Glenn Davis relocates from Hong Kong to San Francisco. To get Rod Taylor to agree to star, the NEA article claimed, 20th Century Fox gave Taylor a contract for three theatrical films.

The website also states that the archives of the University of Iowa Libraries has a copy “of the story for the pilot,†entitled “The Castle†that was written by Robert Blees and Dorothy Robinson (Hong Kong episode “With Deadly Sorrowâ€).

In Broadcasting (2/19/62), Dateline: San Francisco was listed as a pilot for 20th Century Fox to be produced by Jules Bricken (Riverboat) and written by Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts (Mannix). Filming began February 12, 1962.

Wed 4 Apr 2012

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini

SIMON TROY – Waiting for Oliver. Macmillan, US, hardcover, 1963. Originally published in the UK by Gollancz, hardcover, 1962.

The work of Simon Troy (a pseudonym of Thurman Warriner) is distinguished for the eccentricity of its plotting, characters, and construction. Most people in a Troy novel aren’t “normal”; they are obsessed, perverse, secretive, profoundly different.

So, too, the situations in which they find themselves. This is true whether Troy is writing tales of psychological suspense and horror, like Waiting for Oliver, or what might be termed “psychological procedurals” featuring his sensitive Cornish policeman, Inspector Smith. All of Troy’s novels — even the few that don’t quite work — are quietly disquieting and absorbing from start to finish.

Waiting for Oliver is probably his oddest book. It is the story of a frightening, almost symbiotic relationship between two men who have known each other since boyhood: Oliver Townside and the narrator, Alex Monro.

Oliver is the dominant personality, a personification of evil, a kind of modern vampire who, spongelike, absorbs the personas of those around him, corrupting or destroying them. Alex has always been terrified of Oliver, has always hated and pitied him, and yet has always responded to Oliver’s hypnotic power and done his bidding. When they were children, he could not bring himself to expose his friend/enemy as the perpetrator of unspeakable acts of violence.

Nor could he bring himself to seek personal vengeance as an adult, when Oliver maliciously seduced Alex’s sweetheart, Margery, married her, and later cold-bloodedly murdered her.

When the book opens, two years have passed since Margery’s “accidental” fall from a cliff near Petit Sant, Oliver’s home in the Channel Islands. Alex, a teacher in a small secondary school in England, has had no contact with Oliver since then and prefers to keep it that way. But when he receives a telegram announcing Oliver’s intention to take a second wife — Frances, another woman Alex knows — he is drawn back to the islands.

It is then, while once more waiting for Oliver, that he realizes he cannot let the man marry Frances, for surely he will murder her too. He sets out to do what the local police have not been able to do — prove that Oliver killed Margery — and also to free himself from Oliver’s thrall, if necessary to destroy the evil before it destroys him.

The suspense here builds slowly, inexorably, to a terrifying climax on one of the smaller islands. And as a bonus, Troy portrays the Channel Islands (as he does all his settings) with a sharp eye for detail.

The novel does have its flaws: its eccentric construction makes things seem confusing at times, especially in the early pages; Troy withholds vital information about Oliver’s and Alex’s boyhood until much too late in the book; and there are minor points that seem a bit too quirky, that don’t quite ring true. Still, this is a powerful and unsettling work.

Also well-worth investigating is Troy’s only other nonseries psychological suspense novel, Drunkard’s Walk (1961), and his ten mysteries featuring Inspector Smith. Among the best of the Smith novels are Second Cousin Removed (1961), Don’t Play with the Rough Boys (1963), and Cease Upon the Midnight (1964). The last-named title also has a Channel Islands setting.

Under his own name, Troy/Warriner also published a series of novels featuring an outspoken private detective named Mr. Scotter, none of which has been published in this country.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Previously on this blog:

THURMAN WARRINER: Method in His Murder, reviewed by Bill Deeck.

Wed 4 Apr 2012

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Crider

DAN J. MARLOWE – The Name of the Game Is Death. Gold Medal s1184, paperback original, January 1962. Fawcett Gold Medal T2663, paperback, revised edition, January 1973.

The Name of the Game Is Death is Dan J. Marlowe’s best book, which means that it’s just about as good as original paperback writing can get. It’s hard, fast, tough, and terse, with an opening scene so strong that you’ll wonder if Marlowe can possibly come up with an ending to top it. But he does, and it’s good enough to jolt you out of your chair.

Marlowe’s narrator, Earl Drake, is a bank robber and a cold-blooded killer — they don’t come any colder — who works part-time as a tree surgeon. He hates most people and loves animals.

When he’s wounded in a robbery in Phoenix, he sends his partner on ahead with the money and instructions to mail some of it to him each week. At first the money arrives on schedule; then it doesn’t. Recovered, Drake starts for Florida to find out why. Not everyone between Arizona and Florida lives until Drake finishes his trip.

In Florida, Drake gets work as a tree surgeon, makes friends with several of the locals, and even appears to be falling in love. But always in the back of his mind is his desire to find his money and his partner. He does, shortly before the (literally) explosive climax.

Drake’s story is strong stuff, and it moves with the speed of a bullet from his Colt Woodsman. Take a deep breath when you plunge into the story; you might not have time for another before it’s finished.

Warning: Earl Drake was eventually turned into a series character, a sort of secret agent. As a result, in 1972 Fawcett issued a revised edition of The Name of the Game Is Death in which Drake was made a bit more socially acceptable. Find and read the original if possible.

Equally exciting books by Marlowe are The Vengeance Man (1966) and Four for the Money (1966).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Earlier on this blog:

The Vengeance Man, reviewed by Noel Nickol.

And a long look at the differences between the two editions of The Name of the Game Is Death can be found here.

Tue 3 Apr 2012

Posted by Steve under

General[27] Comments

WHAT IS A CRIME CLASSIC?

by Josef Hoffmann

If we were to believe the language of publishers, booksellers and collectors, there is a multitude of so-called “crime classics.†And yet not every crime novel that has exercised a certain appeal on a particular number of readers, even decades after its publication, deserves the attribute “crime classic.â€

At a time of “retromania†(Simon Reynolds), at a time in which computers, the internet and e-books can and perhaps will tend to compile, store and make accessible all texts, longevity in itself is not sufficient as a criterion.

The term “crime classic†denotes a distinction, a seal of quality, which raises the novel concerned above the average, especially when books are produced and distributed more or less industrially in masses. So which crime novels have the prerogative to maintain a presence and to claim the attention of generations of readers?

If we try to determine the particular characteristics of a crime classic, we might concentrate on the intrinsic qualities of the narrative text, such as an ingenious plot and lustrous prose, or on extrinsic features such as its continuous presence in the book market over decades and special regard among literary critics.

At any rate, “classic†in the sense of a crime novel does not mean that it corresponds to the literary-aesthetic ideals of a so-called classic era, that it distinguishes itself from romantic or realistic or other epochal styles, or that it demonstrates a particularly exquisite language.

Classic is also not identical to nostalgic. That said, any nostalgic reading need, satisfied by a certain crime novel that revives good old or bad old times, does not necessarily mean that the novel is not a crime classic.

It seems obvious to assume a complex interplay of the intrinsic and extrinsic qualities of a crime novel, which ultimately lead a particular crime novel to stand the test of time, to still appear “fresh†even after decades have passed, and to enrich its reader.

I now intend to examine more closely how such interplay works, creating tradition and literary history.

While Edmund Wilson’s infamous polemic “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?†might be arrogant, it does provide an opportunity to undertake certain differentiations. A distinction must first be made between “crime classics†and the classics of world literature.

“Crime classics†are not classics that also happen to be crime novels. “Crime classics†require other criteria of attribution. If we were to apply Wilson’s standards of modern classic literature (James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Thomas Mann), there would be at most a dozen crime novels that would meet these standards and deserve the title of “classic.â€

Using Gertrude Stein’s criteria for “masterpieces†would produce even fewer. In her view, masterpieces do not describe the things of reality, recognised by the reader to his enjoyment; rather, they create and embody a being in themselves, something fundamentally new. This is the case in very few crime novels, if at all in any.

Furthermore it should be noted that a “crime classic†is not automatically every work by any crime author who has also written, among other things, a few “crime classics.†If, for example, we consider the best, most successful crime novels by Agatha Christie to be “crime classicsâ€, this does not mean that her weaker publications should also achieve this status.

Crime authors are rarely so perfect, from a literary point of view, to suggest that those who have written a number of “crime classics†will never dip below this level, and always write masterfully. Such an assumption is disproved by many weak crime novels by good authors.

Ultimately, the criteria for all subgenres of crime novels are not the same. Different standards apply to the traditional whodunit, which make the novel a “crime classic,†than to a gangster story or a psycho thriller.

In a whodunit much more emphasis is placed on a perfectly structured, thoroughly logical and at the same time original plot, on the clever distribution of “clues†throughout the text and a surprising and plausible solution to the riddle than is the case in a gangster story.

What is required of all “crime classics,†however, is that they demonstrate a certain superior level of prose, and that their specific dramatic suspense works.

One criterion that is insufficient to qualify a novel as a “crime classic†is some random innovation; e.g., a particular method of murder or a criminal deduction technique, which is presented in a novel for the very first time. In spite of the innovative element a crime novel might still be written using lousy language and a sloppy plot, so that the predicate “crime classic†is not appropriate.

Equally insufficient is the fact that a crime writer (or his works) was read widely at the time and showered with praise by critics. I question, therefore, whether even a single work by Edgar Wallace deserves to be considered a “crime classic†although he was appreciated by highly competent authors such as Gertrude Stein, Dashiell Hammett and H. R. F. Keating.

Positive acknowledgement by literary critics is an extrinsic feature. A prerequisite here is continuity over a long period of time, which does not mean that all criticism highlights the same aspects of a crime classic and appraises them positively. Perspective and standards can shift, particularly over the course of decades.

Not every critic must provide identical reasons for his praise. A further extrinsic characteristic of a crime classic is that it is generally read more than once. Especially in the case of the traditional whodunit a large time span is often left between readings, so that the forgetful reader can try to solve the mystery anew.

But we should remember Chandler’s criterion that a really good crime novel must also provide reading pleasure even if the last chapter is missing (and even if the experienced reader figures out the end of the story).

In other words, every crime classic must possess literary qualities and may not profit merely from the uncertainty as to how the story ends. It must touch the reader, so that scenes, lines of dialogue, comparisons or other elements of the novel become indelible in his memory. It may not leave one cold, but instead must challenge the reader to adopt a position for or against the crime novel or some of the statements contained therein.

More specifically, a crime classic must distinguish itself by means of such a complex power of literary qualities that a single reading, or a reading in a particular historical period, does not exhaust these literary riches, but rather the work provides new aspects for later readings or subsequent generations of readers.

Upon first perusal in youth, the aspects that play a role and are assessed positively will be different to those in more mature years, or in later life. The manner in which this is caused by a crime novel might well remain a mystery to most readers, upon which critics and literary scholars can continue to work. I only wish to warn against awarding the distinction of crime classic prematurely to all old crime novels that appear, in some way, to be worth reading.

To conclude, here are some suggestions related to the discussion: Are the following crime novels crime classics or simply cult novels for those in the know?

Dan J. Marlowe: The Name of the Game Is Death (1962), praised by Ed Gorman, Stephen King.

Ted Lewis: Jack’s Return Home (1970), praised by Paul Duncan, Max Décharné.

Simon Troy: Waiting for Oliver (1963), praised by Mary Ann Grochowski, Bill Pronzini.

Richard Hallas: You Play the Black and the Red Comes Up (1938), praised by David Feinberg, E. R. Hagemann.

Vin Packer: Whisper His Sin (1954), praised by Anthony Boucher, Jon L. Breen.

Mildred Davis: The Room Upstairs (1948), praised by Marvin Lachman, Jean-Patrick Manchette.

Norbert Davis: The Mouse in the Mountain (1943), praised by Bill Pronzini, Ludwig Wittgenstein.

James Reasoner: Texas Wind (1980), praised by Ed Gorman, Bill Pronzini.

Sources:

Italo Calvino: Warum Klassiker lesen?, Munich/Vienna 2003 (English edition: Why Read the Classics, in: The Uses of Literature, 1986)

Raymond Chandler: Raymond Chandler Speaking, edited by Dorothy Gardiner & Kathrine Sorley Walker, London 1962

J. M. Coetzee: Was ist ein Klassiker?, Frankfurt am Main 2006 (English edition: What Is a Classic?: A Lecture, in: Stranger Shores. Literary Essays 1986-1999, New York 2001)

T. S. Eliot: Was ist ein Klassiker?, in: Ausgewählte Essays, Berlin/Frankfurt am Main 1950, 469-511 (English edition: What Is a Classic?, London 1945)

H. R. F. Keating: Crime and Mystery: the 100 Best Books, London 1987

Ezra Pound: ABC des Lesens, Frankfurt am Main 1967 (English edition: ABC of Reading, New York 1934)

Gertrude Stein: Was sind Meisterwerke. Essay, Zürich 1985 (English edition: What Are Masterpieces and Why Are There So Few of Them?, 1940)

Edmund Wilson: Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?, in: Howard Haycraft (ed.): The Art of the Mystery Story, New York 1992, 390-397

Translated by Carolyn Kelly.

Sun 1 Apr 2012

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

REVIEWED BY GEOFF BRADLEY:

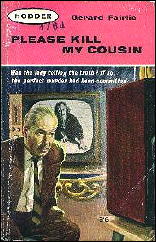

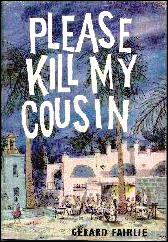

GERARD FAIRLIE – Please Kill My Cousin. Hodder, UK, paperback, 1963. Original edition: Hodder & Stoughton, hardcover, 1961. No US edition.

I’m a sucker for a gimmick. I was browsing a rack of cheap paperbacks outside a secondhand bookshop and saw this. I had read several of Fairlie’s Bulldog Drummond books when I was a boy, following on from Sapper (H. C. McNeile)’s series, and at least one I think of his other books. (Indeed, I have read that McNeile actually based his character on Fairlie.)

This is the sixth and final book in his series about private detective Johnny Macall, and I suspect it was one of the earlier ones in this series that I read. (I can’t remember anything about it of course, but these days it’s hard to remember what I read last week.)

The gimmick is obvious on the contents page which I turned to after I had idly picked the book up. The first part (some 146 pages), Macall narrates as he is hired by a lady to find her long-time friend who has disappeared. He finds that after receiving a large inheritance from her aunt she had set up home with a housekeeper, butler and a chef and maid but that all four have disappeared at the same time that she has travelled to Las Palmas.

Macall interviews a disgruntled cousin, who didn’t inherit, and travels, with his wife Moira, to the Canaries but is unable to find sufficient evidence to prove what has happened.

Now we come to the second part, four pages of correspondence between Macall and his friend Gerard Fairlie (!) in which Macall sends his report (i.e., the first part of the book) to “Gerry” and asks him to use his imagination and come up with a fictional account of what might have happened.

The third part, some 60 pages, is a television script written in response by “Gerard Fairlie” in which he outlines a possible scenario as a television script. The script ends with an announcer asking the audience if this is a “Perfect Murder” and inviting them to send in their solutions as to how the crime could be uncovered.

There will be another programme in a month’s time and a reward of £1000 (quite a sum) will be awarded to the best entry.

In a two page letter to Macall, that makes up the fourth part of the book, “Fairlie” says that Macall’s story has given him an idea for a series on “perfect murders” and that the competition may produce some good ideas and the prize money may even tempt one of the conspirators to enter.

In the fifth and final section, some 36 pages, Macall hatches a plan with his Scotland Yard buddy, Detective Superintendent Francis, that uncovers the crime and brings the criminals to justice.

I wouldn’t recommend this as an outstanding book but I have to say I did quite enjoy it and the gimmick was enjoyably, if a little implausibly, done. There must be other instances of an author inserting himself into a story (other than the Kinky Friedman kind of thing) but inserting himself as a writer helping out his own character is a little unusual.

Editorial Comment: This was the final book in Gerard Fairlie’s mystery-writing career, which began in 1927. If the gimmick in this book sounds as interesting to you as it does to me, let me warn you that right now only a small handful of copies are being offered for sale on the Internet, and most of them are located in New Zealand or Australia. The good news is that one of them, a hardcover edition, will set you back only something like $20, including postage, unless I decide to go for it first.

« Previous Page