September 2012

Monthly Archive

Fri 7 Sep 2012

NORMAN A. FOX – Long Lightning. Dodd Mead, hardcover, 1953. Dell 783, paperback, 1954; several later printings. First published as the short novel “Wire to Warlock,” Zane Grey’s Western Magazine, December 1952.

For those of you always on the lookout for hard-boiled fiction to read, and you have no a priori objections to reading a western, here’s one you might want to hunt down. There are some solid “tough guy” aspects to this 50-year-old novel that may be worth your attention, largely due to the highly individualistic nature of its main protagonist, Holt Brandon, construction chief for the Mountain Telegraph Company. In this book, not only must he get the job done on time, but he has to fight for his life all the while he’s doing so.

There are two obstacles, the first being Mountain’s main competitor, Consolidated, and they do not hesitate in hiring local gunmen to make sure Holt’s crew do not make their deadline. Second, and not insignificantly, is Colonel Templeton, the owner of the Montana land they must cross, an elderly gentleman from the South who imagines that the War Between the States is still going on, and still fighting imaginary battles in his mind.

Holt Brandon plays his cards strictly by the book, and his loyalty to his boss, Sam Whitcomb is never in question. The world of financial matters is beyond him, but what he’s fully aware of is this: If they do not get the wires strung to Warlock from Salish on time, all is lost for Mountain Telegraph.

Here’s a quote that demonstrates that Fox knew exactly what he was writing about, from page 113:

String wire, and you lose yourself in the endless race, not knowing one day from another but realizing that each day is a leaf fallen from the calendar, each days brings the deadline nearer; and always the poles set between the suns seem not enough. The ground is stubborn and repels the pick and the shovel, a batch of insulators proves inferior and has to be returned to Salish, and three of your crew slip away to see the lights of town and buck the tiger and fill a painted woman’s shoe with silver.

Poles are late in arriving, and the crew sent to fetch them reports a brush with hidden marksmen who keep them busy with guns when they should have been using axes. The wire stringers stand idle that day. The long lightning is flung from camp to town, shouting always for more supplies, more men, and you hammer the key constantly and wish that Sam Whitcomb were up and about and doing the job at the other end.

To add some variety to the plot, Holt is not shy around women, but he is caught by surprise when he finds himself the focus of attention of two of them: Gail, the daughter of his boss, and Ellen Templeton, the colonel’s daughter. It is clear which of them he will end up with, if either is to be the case, but that he will lose both of them is a definite possibility, and what Fox does is make sure the reader does not lose sight of that.

So — here’s a western that’s a trifle clumsy when it comes to affairs of the heart, perhaps, but not– ever — when it comes to matters of loyalty and pride, and other qualities that men have, or they’re supposed to.

— Reprinted from Durn Tootin’ #5,

July 2004 (slightly revised).

[UPDATE] 09-07-12. I’ve made no attempt to obtain an exact count of the western novels written by Norman Fox (1910-1960), but if he’d been able to live longer, I’m sure he’d have written a lot more than the roughly 30 or so I’ve quickly come up with.

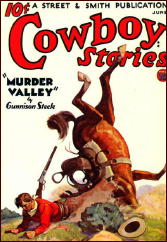

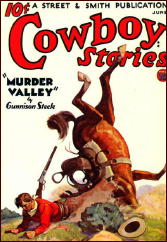

He was a pulpster as well, with nearly a full page of entries already listed for him in the online FictionMags index, a list still under construction. The first of these, by the way, is “The Strange Quest” (Cowboy Stories, June 1934).

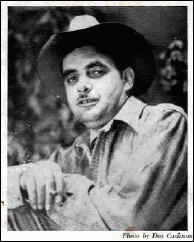

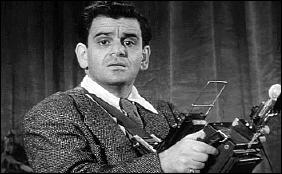

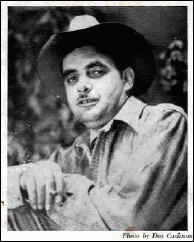

The photo of him comes from the back cover of one the hardcovers I own by him. What’s unusual about it is that it was taken by fellow western and adventure writer, Dan Cushman. I’d love to know more about when, where and why.

Wed 5 Sep 2012

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

FINGERPRINTS DON’T LIE. Spartan Productions / Lippert Pictures, 1951. Richard Travis, Sheila Ryan, Sid Melton, Tom Neal, Margia Dean, Lyle Talbot, Michael Whalen, Karl Davis. Director: Sam Newfield.

Early this year an old childhood buddy of mine gifted me with a box of perfectly-chosen DVDs: no classics, just a lot of stuff I kinda wanted to see but didn’t want to spend much money on. So far, the gem of the set has been Fingerprints Don’t Lie (Spartan Productions, 1951) an enjoyably bad film that passes too quickly for its deficiencies to grow irksome.

Yeah, this is listed as “A Spartan Production,” and Spartan it is, but “Cheapo” might have caught the spirit better, as it was produced by Sigmund Neufeld and directed by Sam Newfield, the driving talents (for want of a better word) behind PRC, which has been widely celebrated as the most penurious studio in Hollywood. Fingerprints carries nobly on in the PRC tradition, with tacky sets, perfunctory acting, and a screenplay that seems more interested in killing time than actually getting anyplace.

What makes it fun to watch, though (for me anyway) is the amusingly slip-shod nature of the thing. Instead of background music we get an organ soloist, just like in the old-time soaps, bridging scenes and setting moods with a turgid melancholia that broke me up every time.

Then, late in the film, we get one of those cinematic conventions that normally go unnoticed: two characters talk about checking out a suspect’s apartment on the sixth floor of the Metropolitan Hotel, and we cut to an exterior shot of the Metropolitan, the camera sweeps up to the sixth floor, and we cut to the two characters walking into the apartment.

It’s the kind of movie-shorthand you’ve probably seen dozens of times and never noticed. Only in this case they couldn’t afford to send a cameraman out for an exterior shot, so they simply panned up a photograph of the hotel —- which might have worked except that no one noticed the photo was printed backwards and we see the words LETOH NATILOPORTEM in mirror-image!

Still later, the gaffes come fast and funny as the Police close in on the Crime Boss and his Moll in a rather economical–looking suite. When they tell the baddie he’s going Downtown, the obliging Moll opens her purse, ostensibly for lipstick, but holds it up what seems like an eternity as he sees the gun inside and they exchange significant glances. At some length.

Much later (it seems) he reaches inside the purse and fumbles around for several seconds before finally pulling the gun out — upside down! Whereupon he spends several more seconds getting it pointed at the cops, who promptly register surprise. Now that’s acting!

Following a bit of stand-off, the Crime Boss eventually shoots a cop, who bends sharply forward, as if hit in the stomach, then apparently remembers some long-ago instruction from the director, straightens up and grabs his supposedly-wounded shoulder. Bullets fly (or rather, bullet-type noises fill the soundtrack) till our bad guy (WARNING!) “falls” out a window.

Actually, we see him slide out the window-set, lie down on a not-quite-hidden platform and roll out of view. Which at least gets him mercifully out of this turkey.

I should perhaps add that the unfortunate actors in this thing at least carry on manfully, ignoring the paucity of their surroundings and the deficiencies in the script. In one scene, the prosecutor is played by Tom Neal, who would soon be facing a prosecutor himself. An actor named Sid Melton gamely struggles to apply comic relief as a newspaper photographer who can’t work a camera, and Karl “Killer” Davis makes a rather effective Hood. Altogether a game bunch, and it’s just a pity they had so little to work with.

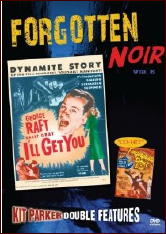

Editorial Comments: This film, if you would like to obtain a copy, is easily available on DVD, as part of a two-for-one “Forgotten Noir” pair of offerings. See the image above. I’ll Get You, with George Raft and Sally Gray, is the main feature, with Fingerprints getting only second billing (in very small print).

Also worth noting, as Dan has already pointed out in a comment following Michael Shonk’s recent review of Philo Vance, Detective, this is one of the movies that was re-titled (as Fingerprints) and edited down to less than thirty minutes in a syndicated package of films sold to TV stations in the early 1950s.

Wed 5 Sep 2012

ANN CLEEVES – Sea Fever. Fawcett Gold Medal, paperback original, 1st printing, October 1991. Macmillan, UK, hardcover, 1993.

This is the fifth mystery novel in which inveterate birdwatcher George Palmer-Jones has become involved with a case of murder. It shouldn’t be too surprising: even though he’s now actually a retired civil servant, he and his wife Molly have become partners in an “enquiry agency” as a means to keeping themselves busy in their declining years.

George hates the term “private detective,” but there is no escaping it: whether “enquiry agent” or PI, that’s the kind of work they do. (*) George has birds on his mind most of the time, though, and if it weren’t for Molly to push him, I think his investigative business would be nothing at all, in no time flat.

In Sea Fever they’re hired to trace a wayward son who refuses to come home, or to acknowledge the existence of his worried parents in any way. That he’s also an ardent birdwatcher makes the Palmer-Joneses the ideal couple to track him down. They catch up to him momentarily on a sea cruise/birdwatching expedition, but they lose him again almost as quickly at the hands of a killer.

Murder at sea means a limited number of suspects, and this is classical detection at very nearly its highest level and its most overwrought, boosted by little annoying hints of what is yet to come and a (female) police inspector who finds her own life close to exploding out of control.

Don’t get me wrong, though. While this may not be the equivalent of John Dickson Carr in plot complexity, it is a pleasant voyage through waters charted several times or more. Every time I take the trip, I enjoy it just about as much as the time before, and that’s the kind of book this is.

(*) I’ve just checked John Conquest’s Trouble Is Their Business (Garland, 1990), a superb compendium of just about every other fictional PI you could name, and as it happens, he misses these two. They’re borderline, I’d say, but by Conquest’s own definition, they’re PI’s, and they should be in there.

— Reprinted from Mystery*File 36,

(slightly revised).

[UPDATE]. 09-05-12. And for what it’s worth, the Palmer-Joneses are not included on Kevin Burton Smith’s Thrilling Detective website either. Kevin doesn’t miss many, but this is one pair of PI’s I think he he has. A lengthy profile of the author by Martin Edwards can be found here, along with a long list of all her mysteries. (She’s done more than just this one series.)

The George & Molly Palmer-Jones series —

A Bird in the Hand. 1986.

Come Death and High Water. 1987.

Murder in Paradise. 1988.

A Prey to Murder. 1989.

Sea Fever. 1991.

Another Man’s Poison, 1992.

The Mill on the Shore. 1994.

High Island Blues. 1996.

Tue 4 Sep 2012

REVIEWED BY MICHAEL SHONK

PHILO VANCE, DETECTIVE. Official Films, 18 minutes. (Originally Philo Vance’s Secret Mission, PRC, 1947; 58 minutes). Cast: Alan Curtis, Sheila Ryan, Tala Birell, Frank Jenkins, James Bell, and Frank Fenton.

Philo Vance, Detective did not include any onscreen credits except for the actors listed above. (The actor listed as Frank Jenks in all the databases is credited on screen as Frank Jenkins.) According to the TCM (Turner Classic Movies) database and imdb.com, the original film was written by Lawrence Edmund Taylor and directed by Reginald LeBorg. S. S. Van Dine received no screen credit.

In 1947 PRC (Producers Releasing Corporation) made three Philo Vance theatrical films: Philo Vance’s Secret Mission, Philo Vance’s Gamble, and Philo Vance Returns. Both Secret Mission and Gamble featured Alan Curtis as Philo with his assistant Ernie Clark played by Frank Jenkins. In Returns Philo was played by William Wright (without Jenkins).

The PRC version of Philo Vance resembled the generic detective hero of the average 1940s Poverty Row studio film series more than S. S. Van Dine’s creation.

By the 1950s television had become the gluttonous beast with an insatiable appetite for content that it remains today. When the networks were unable to fill the needs of the TV stations, the stations turned to syndicated producers such as Ziv, CBS TV-Films and Official Films. Distributors such as MPTV (Motion Pictured for Television) acquired the rights to B-movies, cartoons and short films such as Philo Vance’s Secret Mission and sold them to the hungry hungry hippos aka the local TV stations.

One of the major problems facing MPTV and others was local stations taking a dull ax and editing programs to suit the local station needs. This could be the cause for a 58-minute theatrical film to exist in a renamed TV version suitable for a half hour time slot. More likely, Official Films, one of the top syndication companies at the time, did the editing and sold it in a package of half-hour mysteries.

Fortunately, the TCM database has a complete synopsis full of spoilers and credits for the 58-minute film short.

Jamison (Paul Maxey), co-publisher of pulp magazines, has invited writer Philo Vance to his office to discuss the possibility of Vance writing a mystery based on Jamison’s former partner’s murder seven years ago. With his assistant Ernie Clark and a woman who is not introduced, says nothing and no one says anything to her during the long scene (she is Vance’s secretary Mona), Vance meets the suspects.

Mona (Sheila Ryan) will be in nearly every scene of Philo Vance, Detective, while most of the rest in this scene will end up victims of the missing forty minutes and not be seen again.

Jamison’s other partner is upset over the idea of leaving pulps to publish “books.†The company’s two main writers also hate the idea of mystery books (there are too many of them now). When Jamison announces he had solved the murder of the dead partner, office secretary and victim’s wife (Tala Birell) faints. Jamison invites Vance to his house that night to discuss the case.

Vance and Mona arrive to meet Jamison. They hear gunshots and a cry for help. The two break into Jamison’s home to find blood on the floor but no body (just like the earlier murder). They call and wait for the sheriff.

“I think I am going to faint,†says Mona, half seriously.

“Why don’t you wait until the police come and I’ll catch you in my arms,†suggests Philo, who is busy on the phone.

Vance and Mona leave but a motorcycle cop chases them down. The murdered man’s body is in Vance’s car trunk. Next we see a cop using the police radio informing all police cars to look out for an armed and dangerous killer, and the cop is nice enough to add Philo “and girl companion†have been released.

Now the editing becomes noticeable. We miss all the scenes with the suspects, clues to motive, where the murder weapon came from, and information about the first murder. One entire character, Joe the cover photographer, ends up on the editing floor.

Instead we jump to Vance and Mona driving to the first victim widow’s home. They are followed and shot at. Vance fights with the bad guy who runs away unseen in the dark. Vance rushes to the widow afraid she would be next. Instead he finds her packing for a cruise where she plans to marry her finance.

More scenes vanish including (according to the TCM synopsis) the denouncement scene where Vance names his girl friend Mona as the killer (that I would need to see to believe).

But it was all a ruse to trap the killer. At the cruise ship the killer is revealed, Vance suggests he and Mona take a cruise together, but then he heads for the exit when she suggests they get married at sea. She stops him with a long kiss.

It would be unfair to judge the cast and production with forty minutes missing from the 58-minute film, but the story holds up considering. There are times the viewer is confused by what is going on such as why does Vance think the widow is in danger. But while the editor of this television version has removed the mystery, the story barely survives to find a home in the crime genre with the relationship between Vance and girl friend Mona providing most of the entertainment.

Sources: TCM.com database, IMDb.com, Billboard. If you wish to avoid spoilers you can read Steve’s review of the original film here. I need to find a copy of the original, if only to see Sheila Ryan posing for a pulp cover.

Mon 3 Sep 2012

I’m doing much better. I was hoping to get something posted this evening, but after spending some time trying to catch up with emails and not quite succeeding, I decided to play it cautious and not push myself when I shouldn’t. Look for something new tomorrow, though, or if not, Wednesday for sure.

Coming soon are a review by Michael Shonk of an unusual Philo Vance appearance on TV, a long installment of Mike Nevin’s usual monthly column, Dan Stumpf’s opinion of a movie you probably never heard of, Fingerprints Don’t Lie (1951), and as I’m often fond of saying, much more.

« Previous Page