October 2013

Monthly Archive

Mon 21 Oct 2013

MYSTERY WOMAN. Made for TV: The Hallmark Channel. First telecast: 31 August 2003. Kellie Martin, Robert Wagner, J. E. Freeman, William R. Moses, Constance Zimmer. Written by Michael Sloan. Director: Walter Klenhard.

I missed this when it was first shown, and since I try to keep an eye out for good, solid detective movies, even though I’m not always able to watch them at the time, I’m not sure how that might have happened. After all, if the basic premise is someone inheriting a musty old mystery bookstore and using that as a basis to solving murders, how could I resist?

That someone is Samantha Kinsey (Kellie Miller), and Jack Stelling (Robert Wagner) is the true-crime writer whose death by hanging in a locked room is the suicide that Samantha does not think is, um, a suicide.

Assisting her are a grizzled old geezer named Ian Philby (J. E. Freeman) who is a carryover employee of Samantha’s uncle in the bookshop, and Cassie Tilman (Constance Zimmer), who as an Assistant DA is good at assisting (and seems to have no other regular working hours, other than being on hand when Samantha is out searching for clues).

Convinced that the death is indeed a suicide is police lieutenant Robert Hawk (William Moses), conveniently ignoring all of growing evidence otherwise, but on the other hand, it is equally hard to ignore the door that is solidly bolted on the inside.

There are a lot of the other vintage bits and pieces of the vintage detective story, a la MURDER, SHE WROTE, combined with the Carolyn Hart stories in which Annie Darling runs a mystery bookstore as well as solves mysteries in the “Death on Demand†series. There is also a bit of what – I hate to use the term – is called “woo woo†when psychic impressions of a murder committed 10 or 15 years earlier are needed to understand why an author of true crime books might need to be silenced today.

As a mystery buff, Samantha also has the skills needed to pick locks when the time is needed. This almost goes without saying. I thought Kellie Martin was too young for the part – she looks and acts in this movie as though she were 18 – but I am afraid that it is I who am (is?) getting old. She is 29 and has been in a host of various other TV series and dramas that I have never seen, including being nominated for an Emmy for her role as Becca Thatcher in LIFE GOES ON, ABC, 1989-1993.

The character I enjoyed the most was the relatively aged Philby, a man of the gutter who continued to surprise Samantha with his knowledge and abilities – definitely a man of some mystery beneath that weather-beaten and faded facade. (I don’t suppose I identified with him, or anything.)

No mystery film with references to Ed McBain, Anthony Boucher and John Dickson Carr can be all bad, but neither does it rise to more than knee-high to any of them. Extremely derivative in nature, in other words, but other than the “woo woo,†is a well-natured, pleasant to the palate sort of way. Sloan, the screenwriter, started his career with McCLOUD (1970) and HARRY O (1974), so it isn’t as though he’s never been around the block before.

And, I have discovered – since it was so obviously left open that way – that if not a weekly series, there is another Hallmark movie with (many of) the same characters coming, starting in production as of Fall 2004. Robert Wagner won’t be in it, for example, but other than that, and reading through the lines of what I said and what I didn’t say, I’d say that you should be on the lookout for it.

— September 2004

[UPDATE] 10-21-13. Advice, that for better or worse, I did not take myself. I may have purchased some of the later MYSTERY WOMAN movies when they came out on DVD (it did indeed become a series), but I never watched them. I believe the reason to be this. When I learned that J. E. Freeman was replaced by Clarence Williams III in the ten later episodes, I discovered that I wasn’t interested any more, or certainly at least not as much.

Sun 20 Oct 2013

VOICE WITHOUT A FACE:

Finding a Face for Philip Marlowe

by David Vineyard

Raymond Chandler seldom painted word portraits of his heroes, perhaps because of the falter in his first story, “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot,” when he gave his protagonist Mallory a “diffident” touch of gray in his hair. We know what the Chandler hero looks like; tall, dark, masculine, attractive to all society types, but if you read closely you will notice that complete as he is, Philip Marlowe has no face. That wasn’t a problem for Chandler, but it would become one in other media.

That became Hollywood’s quest when they took notice of Chandler’s work: What did Philip Marlowe look like? Even Chandler struggled with that, veering from Cary Grant to Dick Powell, from Fred MacMurray to Humphrey Bogart — Chandler’s favorite, but not how he describes Marlowe in a letter that sounds suspiciously like MacMurray and Powell, and a young bartender he met in Hollywood, Robert Mitchum.

The first screen Marlowe’s weren’t Marlowe at all. George Sanders’ Falcon took on Farewell My Lovely as The Falcon Takes Over, and Lloyd Nolan’s Michael Shayne took on The High Window as Time to Kill, and while both were faithful adaptations of the books, they weren’t Philip Marlowe. Marlowe was still faceless. All that changed in 1946.

Well, actually it changed in 1945, but it was 1946 before anyone knew, and by then Marlowe already had one face, ex-crooner and male ingénue Dick Powell in the career changing Murder My Sweet, based on Farewell My Lovely, the Edward Dymytrick film that gave that became mid-wife to the film noir genre that had been in labor since German expressionist cinema in the teens.

Powell is much as we imagine Marlowe, a bright attractive, but not devastatingly handsome, man, a bit shop worn, a bit defensive, and too human for his own good. To that Powell brings a post-war cynicism common to many ex-G.I.s, an ironic voice tinged by sarcasm, and a leery eye toward the idea he is so devastating that women like Claire Trevor will just throw themselves at him, at least without a distinct curve on the act. Bluff, brash, rude, and surprisingly gentle, Powell seemed to find every niche of Marlowe’s character, and would even play Marlowe again of television in an adaptation of The Long Goodbye.

Howard Hawks and screenwriters Leigh Brackett, Jules Furthman, and William Faulkner had attempted Marlowe earlier in 1945, but a year too early for the slow to change moguls, who held the film back until Dymytrick’s film hit the boxoffice. The money showed them the light and The Big Sleep was rushed into release along with the second iconic face of Philip Marlowe, Humphrey Bogart.

Physically Bogart was no more Marlowe than he was Sam Spade, but he brought to the character and screen a world weary romanticism and guarded heart only hinted at in the Powell Marlowe. Teamed with real-life wife Lauren Bacall, Bogie’s Marlowe has a subdued eroticism running beneath the tough façade. Add to that a very real tendency to defend the helpless and tilt at windmills, and Bogart may come closest to the fully developed Marlowe we see in Chandler’s masterpiece, The Long Goodbye.

Sadly the film is deeply flawed by the ending imposed by the censors, one so absurd it comes close to ruining a masterpiece. Even seeing it the first time in my teens I can recall thinking John Ridgey’s (Eddie Mars) fall guy was covering up for someone, Carmen Sternwood, who conveniently drops out of the film midway through the proceedings before Marlowe can throw that famous old maid hissy fit and throw her out of his apartment and bed.

Still, even Chandler was impressed by what Bogart brought to the role. Powell’s Marlowe is still half a genial boy turned rude. Bogie’s Marlowe is a man.

That said, I agree with noir critic Eddie Mueller, The Big Sleep is as much a screwball comedy as it is film noir.

George Montgomery is the next Marlowe, and not bad in John Bahm’s The Brasher Doubloon. based on The High Window. Replete with a silly mustasche, Montgomery is Marlowe lite.

Still he fares better than the next Marlowe, who for the most part is a voice without a face, Robert Montgomery in his own film of Lady in the Lake. Using an experimental subjective camera technique the film falters, despite good work from its star/director and a fine cast including Audrey Totter, Lloyd Nolan (outstanding), and Tom Tully. The problem is it doesn’t look like a movie half so much as a live television broadcast.

Save for Phil Carey’s slick Marlowe on a brief lived television series and Powell’s second outing, we don’t get another Marlow until James Garner in the sixties take Marlowe, based faithfully on The Little Sister.

Garner’s Marlowe has generated a lot of criticism, but in many ways he is the epitomy of the Marlowe in that book, and the wary humor and slow exasperation that would make him a star is ideal for the character. He sparks in the scenes with cop Carroll O’Connor, Rita Moreno’s stripper, and Gayle Hunnicutt’s film star, and Bruce Lee has two of the best scenes of his career in a small role.

That said, the critics and many fans savaged the film and Garner. Maybe if he had tried a fedora and trenchcoat …

Elliot Gould is a terrific Marlowe — in audio books — on screen he’s not so good, though not even Bogart could have played the role to anyone’s satisfaction in Robert Altman’s petty tantrum of a film because of Chandler’s homophobia, The Long Goodbye. The movie is badly acted, hard to follow, and completely foreign to the character. Altman so disliked Chandler and Marlowe he undercut his own film, and even a Leigh Brackett script can’t save it.

On my own personal list of the worst films ever made this ranks high. I have no problem with Altman disliking Chandler, or even wanting to savage the mythos, but not in a bitchy and at times campy film that plays like something made by the Hasty Pudding Club, arch, snide, and boring.

By the way, if I wasn’t clear, I don’t like it.

Too old, too fat, too weary, we finally get Robert Mitchum’s Marlowe in Farewell My Lovely, and it is a lovely one. Dick Richards’ moody recreation of noir and Mitchum’s well earned cynicism make this film work, and he’s ably abetted by another noir veteran John Ireland as Nulty, the cop.

Alas, almost no one else in the film is up to them, and Richard Kiel’s Moose Malloy will make you yearn for Mike Mazurki and Ward Bond, who played the role in earlier films. It’s a singularly bad performance in a role vital to the film. Like me, you may well wonder why Marlowe didn’t just shoot the hulking jerk in self-defense.

But even with that, Mitchum manages to give us close to the perfect Marlowe, if only it had come even ten years earlier.

And even he can’t save The Big Sleep, which moves Marlowe to contemporary London, and falters badly despite the presence of James Stewart, Oliver Reed, and Richard Boone as the sadistic killer Canino. When Colin Blakely dies in the Elisha Cook Jr. role, you almost envy him being out of this. Still that scene and a few others work, and you can see where it might of been.

Powers Boothe gets the part for the HBO series Philip Marlowe, and he’s great in well done adaptations of the short stories, but Danny Glover as a black Marlowe in the Fallen Angels adaptation of “Red Wind” doesn’t do half so well, largely because they add nothing to the story of the role even though Glover is a black Marlowe in the forties. It’s as if the story is set in a parallel universe where prejudice never happened, he’s no Denzel Washington and Easy Rawlins ,just a private detective who happens to be black.

To date, James Caan is the last Marlowe in a made for television film of The Poodle Springs Murders, based on Chandler’s unpublished last novel completed and published by Spenser’s Robert B. Parker. Caan’s older Marlowe, confronting love, marriage, and wealth is a new dimension, but when things get rough he’s every bit Marlowe. It’s an exceptionally well done film, and it captures the unease of Marlowe in the new world of the late fifties and early sixties.

Marlowe is also available on radio and audio books. Van Heflin and Gerald Mohr essayed the role on the classic radio production from the forties while Elliot Gould and Daniel Massey (Raymond’s son) are the audio book voices, and both very good, while more recently Ed Bishop (UFO) has been Marlowe’s voice on BBC 4 in several readings and dramatizations.

Still Marlowe remains an elusive voice. You’d know him if you saw him or heard him speak, but you never really have so you remain wary. Some of that is Chandler’s intent, since Marlowe is everyman as the hero, that famous man “good enough for any world” from the essay “The Simple Art of Murder.”

Philip Marlowe is a living breathing flawed human being; he’s a hero because he doesn’t let that stop him. He’s a man because he questions the motive and necessity of those heroics. He’s Philip Marlowe because he does those things in an iconic literary voice that has so come to dominate literature even today’s literary icons use it. (Michael Chabon for one.)

The fact is he doesn’t have a face — or need one. He has a voice, and no actor, good or bad, can ever take that away from him, or us, and I don’t think there is a reader who ever read a page of Raymond Chandler who wouldn’t know him anywhere.

Sun 20 Oct 2013

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

THE PEARL OF DEATH. Universal, 1944. Basil Rathbone (Sherlock Holmes), Nigel Bruce (Doctor Watson), Dennis Hoey (Inspector Lestrade), Evelyn Ankers, Rondo Hatton. Based on the characters created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Director: Roy William Neill.

One indisputable “B” Classic is The Pearl of Death, seventh in Universal’s Sherlock Holmes series with Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce, and my favorite of the set.

Holmes purists object to the modernizing of the series, and to the portrayal of Watson as a buffoon, but I find the atmosphere of these things charmingly old-fashioned — no car-chases or shoot-outs, and very sparing use of phones and electric lights — and I appreciate Nigel Bruce’s shtick for its own sake; every “B” series had to have Comic Relief and his was rather good of its type.

At that, Watson’s a couple laps ahead of Dennis Hoey’s delightfully dense Inspector Lestrade, whose exchange …

HOLMES – “Two persons found with their backs broken and smashed crockery all about. What do you make of that?”

LESTRADE – “Coincidence, I calls it.”

… seems impressively obtuse even for a Movie Cop.

But Pearl scores points mainly as an atmospheric horror movie. It offered Rondo Hatton his first “starring” part, in the expert hands of director Roy William Neil, who exploited “the Creeper” with real Gothic flourish. Here, as never before or since, there’s someone using camera angles, lighting and background to lend the character a screen presence that the actor never really had.

There’s also a particularly fine climax — memorable enough that it appeared again later that same year in the better-known Murder My Sweet.

Fri 18 Oct 2013

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Robert J. Randisi

JONATHAN VALIN – Natural Causes. Congdon & Weed, hardcover, 1983. Avon, paperback, 1984. Dell, paperback, 1994.

Since the appearance of his Harry Stoner novel, The Lime Pit (1980), Jonathan Valin has been hailed as among the best of the present-day private-eye writers. Of the first Stoner adventure, Publishers Weekly said, “Wow! One of the roughest, toughest and most completely convincing private eye novels in a long time.”

Other critics have praised Valin as the second coming of Chandler. That may not be fair, since Valin is a good writer and storyteller in his own right, and Stoner, a PI who works out of Cincinnati is a fully individuated character.

In this, the fifth Stoner novel, the PI is hired by American Productions to go to California and find out who killed the head writer of their biggest soap opera, on Quentin Dover. In describing Stoner’s investigation. Valin also vividly depicts the world of a big-time soap opera — of which he knows much. He spent a year as a story consultant on a popular daytime soap.

Stoner runs the gamut of Hollywood personae: directors, actors, agents, not to mention the victim’s beautiful alcoholic wife. Add drugs and murder and a jaunt south of the border, and you’ve got the story of how and why a man with a half-a-million-dollar-a-year job would get himself involved with something that could — and did — get him killed.

Valin may indeed be one of the best of the present PI writers, but to compare him to Chandler is to do a disservice — one that critics all too frequently perform.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Editorial Comment: My review of The Lime Pit, Valin’s first Stoner novel, can be found here. I also reviewed Final Notice, the second book in the series here, a post that also includes some comments about the author and a complete bibliography.

Tue 15 Oct 2013

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

PATRICIA HARWIN – Arson and Old Lace. Pocket, paperback original; 1st printing, Feb 2004.

Oh, why not. I’m going to quote all of the first two paragraphs. Telling her own story is Catherine Penny:

I pulled the car in close to the hedgerow and turned the key, and that amazing silence came down. It was the silence I had been waiting for more than a year, since my husband had left me, since I’d decided my only hope of peace lay in the ancient rhythms of an English village.

I used to wake in our apartment on West Eighty-third and listen for that silence through Manhattan’s background hum. Keeping by long habit to my side of the bed, I would see behind closed eyelids the narrow country road and the old cottages with roses in bloom on their walls, as they had been when Quin and I had first come to Far Wychwood.

I submit to you that there are few mystery novels that summarize their mood, their setting, and one of the characters as quickly as this. Catherine is in her sixties, a recent grandmother — her daughter and her husband live not too far away, near Oxford — and as you’ve gathered, newly divorced.

There are challenges for everyone in this world, but packing up and moving across the ocean by yourself, leaving your previous life behind, is not one that most people would voluntarily undertake. Across the road, Catherine has a neighbor, an ill-tempered old man who loves alone, nearly incapable of caring for himself, and considered dishonest by the surrounding townspeople. And thereby lies the tale.

When old George’s house burns down, it is Catherine who hears his dying words. And when a body is found in the churchyard next to a huge ornamental cross, who is nearby? Catherine again.

This is the first of a series, and for the most part, it starts off on the right foot, especially when it focuses on Catherine’s life: her struggles with her daughter, who has her own views of raising children; her attempts, largely successful, to make friends with her new neighbors; her bouts of nostalgia with a marriage that was so happy and then so suddenly wasn’t.

Not so successful is the mystery itself, as elements of the plot so obvious to the many-times-over detective fiction reader go flitting over the heads of the people in Catherine’s close circle of new friends, which includes the local constabulary, Detective Sergeant John Bennett. (Not a love interest. He’s happily married.)

That it slips Catherine’s mind to tell Sgt. Bennett everything she knows causes considerable problems as well. Red herrings and false trails abound, but if you stay with the obvious, you’ll be headed in the right direction. You won’t know all — the pieces don’t go together that easily — but you’ll be idling your thumbs for a bit while the story catches up.

And Catherine Penny, prone as she is to rash and impulsive behavior, is a bit of fascination in herself. It’s too bad that we’ll have to wait until Fall of 2005 for a return visit, scheduled to be told in Slaying Is Such Sweet Sorrow.

[UPDATE] 10-15-13. Unfortunately, as it turns out, there were only the two books in the series. 2005 was about the time (as I recall) that Pocket cut way back on “genre” fiction: mysteries, science fiction and westerns — one large implosion and they were all gone — and that may have been one of the reasons that Catherine Penny had only the two cases on record.

Mon 14 Oct 2013

REVIEWED BY MARVIN LACHMAN:

THE RACKET. RKO Radio Pictures,1951. Robert Mitchum, Lizabeth Scot, Robert Ryan, William Talman, Ray Collins, Joyce Mackenzie, Robert Hutton, Virginia Huston, William Conrad, Walter Sande, Les Tremayne. Screenwriters: William Wister Haines & W. R. Burnett. Director: John Cromwell.

It may be a cliché, but they don’t make pictures like The Racket any more. It was filmed in black and white and gives us characters portrayed in black and white. Robert Mitchum is a tough, incorruptible cop, and Robert Ryan gives one of his usual strong performances as a psychopath.

The supporting cast is especially noteworthy, including William Talman and Ray Collins six years away from their success on the Perry Mason Series, though playing very different roles. This time Talman is the honest police officer; Collins is a sleazy district attorney. Also around, and underacting almost to the point of somnolence, is William Conrad, that great radio actor who would later be Cannon and Nero Wolfe on television.

There are no great surprises in The Racket, but no disappointments either, as a tight script, co-written by W.R. Burnett, and John Cromwell’s clean direction provide a satisfying movie.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 10, No. 1, Winter 1988.

Sun 13 Oct 2013

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Julie Smith

ROBERT UPTON – Fade Out. Viking, hardcover, 1984. Penguin, reprint paperback, 1986.

You could love private eye Amos McGuffin for his name alone — but he also has a wry way about him. After McGuffin crashes two cars, Ronald Worthy, the president of Executive Rent-A-Car, denies him any more vehicles. “Isn’t that just like Ron,” says our hero to the clerk. “As if I were the only guy sleeping with his wife.”

McGuffin lives in San Francisco, where he hangs out at Goody’s bar, putting away Paddy’s when he isn’t on a case — which is just about all the time of late. In fact, he’s just bending an elbow when Nat Volpersky tracks him down at Goody’s. It seems Volpersky’s son, Ben Volper, a Hollywood producer, is thought to have committed suicide by wading out into the Pacific Ocean after leaving an unsigned note on his typewriter.

But Volpersky doesn’t believe it; and Izzy Schwartz the deli man, his only friend in California, has recommended McGuffin to find his son. That means McGuffin has to go to Los Angeles, where he encounters the Bronx Social Club- a group of Ben’s childhood friends who’ve made it big in show biz. “Who else can you trust?” Volpersky asks.

But McGuffin isn’t so sure the old neighborhood pals are trustworthy. He’s even less inclined to put his faith in Aha Ben Mahoud, a wealthy Arab who financed Ben’s last picture. And he has serious doubts about Pedro Chan, the six-foot-six cop assigned to the case.

After pursuing a single-minded inquiry throughout most of the book, he suddenly sees the light and pulls the solution out of a hat. Upton didn’t really play fair on this one, McGuffin’s latest case. (He made his debut in 1977 in Who’d Want to Kill Old George?) But no matter. Even though we can’t see it coming, the denouement is ingenious. And McGuffin is a delight.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

The Amos McGuffin series —

Who’d Want to Kill Old George? (n.) Putnam 1977.

Fade Out (n.) Viking 1984.

Dead on the Stick (n.) Viking 1986.

The Farberge Egg (n.) Dutton 1988.

A Killing in Real Estate (n.) Dutton 1990.

Sat 12 Oct 2013

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

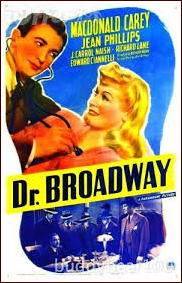

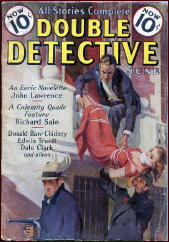

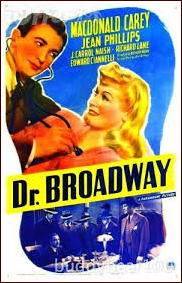

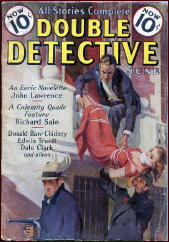

DR. BROADWAY. Paramount, 1942. Macdonald Carey, Jean Phillips, J. Carroll Naish, Richard Lane, Eduardo Ciannelli. Joan Woodbury, Gerald Mohr, Warren Hymer, Olin Howard, Frank Bruno, Sidney Melton, Mary Gordon, Jay Novello. Screenplay: Art Arthur, based on the short story “Dr. Broadway” by Borden Chase in Double Detective Magazine (June 1939). Directed by Anthony Mann.

Dr. Broadway … Specialist in Heart Trouble … and Lead Poisoning

The lights of old Broadway are flashing over Times Square, neon and traffic, crowds and honking horns, and a pretty girl on a ledge.

So what’s new?

Not much for Dr. Timothy Kane, Dr. Broadway (Macdonald Carey), a smooth taking GP who was raised and sent to college by the people of the Broadway streets when his much loved newspaper man father died. On this night there is a pretty blonde girl on a ledge (Jean Phillips — Ginger Rogers stand-in — and really nice legs I might add) and his old pal Detective Sergeant Pat Doyle (Richard Lane) bets him a ten spot he can’t talk her down.

Of course she has no intention of jumping. It’s a publicity stunt — but she didn’t know it could send her to jail, so Kane has to keep her out of jail — which is how he ends up with a leggy blonde receptionist.

Meanwhile Vic Telli (Eduardo Ciannelli) is fresh out of jail, a haunted gunman sent up by the Doc’s testimony. Everyone assumes Vic wants Doc dead — but what he really wants is a favor. Vic is dying: “I’m up to my neck in my own grave …” and wants Doc to see his innocent daughter gets the $100,000 dollars he has put back for her legally.

How much trouble could that be?

Pat: Doc, will you tell me why you hang around Times Square getting mixed up with these broken down Cinderella’s, Broadway screwballs, stale actors … I’m afraid they’re gonna jam you up …

Doc: I don’t know Pat. Maybe it’s because they need me more.

But jammed up he is. Telli is murdered in his office (fried by a heat lamp) and Doc promptly knocked out and framed. Someone wants Telli’s hundred grand for themselves.

Pretty soon Doc is on the run from the cops and the crooks. And then his new receptionist gets kidnapped.

All they want is the money. But Doc is in a cell and his only hope is to run a con on the kidnapers and rely on his army off the Broadway streets — grifters, hoods, news vendors, and the like.

In the meantime Doc is, as crooked haberdasher J. Carroll Naish puts it, “… half way between the hot foot and the hot seat.”

And you just know Doc and the girl are going to end up back on a ledge over the streets of New York before it’s over.

This handsomely shot B-programmer was Anthony Mann’s debut film. It is mostly shot at night in the reflected shadow of flashing neon and with the constant chatter and blare of Times Square in the background. It is peopled with a colorful cast out of central casting by way of Damon Runyonville and moves at a rapid pace full of fast talking and faster thinking.

Dr. Broadway is based on a series of stories written by Borden Chase for the pulps and was the pilot for a possible series that didn’t develop sadly. Chase may be more familiar to you for his books that became films (sometimes with his screenplays) like Red River and Lone Star.

Macdonald Carey had a long career as a mid-level leading man, and was always reliable. He brings an earnest and easy going charm to the central character as Dr. Timothy Kane, and Jean Phillips is good as the slightly dizzy blonde receptionist/girl friend caught up in his world.

Richard Lane could play good but frustrated cops in his sleep (he was most often the brunt of Boston Blackie’s adventures), while Ciannelli had at least one really good scene as the haunted gunman (reminding us how seldom he was used as effectively as he might have been) and J. Carroll Naish has some fun as the crooked haberdasher behind it all. Gerald Mohr appears briefly as a hood not long before he would be the voice of Philip Marlowe on radio.

There is no real mystery here, mostly just a fast paced crime drama.

Familiar faces like Warren Hymer, Sid(ney) Melton, Olin Howard, Mary Gordon, and Jay Novello round out the cast as various Broadway types.

Now, before someone starts, this is a slick fast paced, exciting B-programmer, but despite the direction of Anthony Mann, it is not noir or even proto noir. There are a few touches that will eventually become noir, but they were nothing new to this kind of film in 1942, and good as it is, entertaining as it is, it’s not a precursor of film noir.

You only have to look at a film like I Wake Up Screaming to see the difference. It’s far above average, but in many ways, it could have been made at any time from the start of the talkies as a slick mix of crime, humor, and characters. At most its a cousin of noir-like Mann’s Two O’Clock Courage.

There is an almost indefinable quality that makes a film noir, and this one doesn’t have it, even though it touches on some of the themes and styles.

On a personal note, it took me over twenty years to catch up with this one, ever since I read about in William Everson’s The Detective In Film. Usually when you wait that long it is a disappointment — this one is not. It is everything advertised, and the copy I have from the collector’s market is only a little soft, but otherwise extremely good.

This is a superior B-programmer from a time when they were often the best thing on the bill. Heat up the popcorn and enjoy it. If you look real close you will even see some of the promise of Anthony Mann to come. But either way it is a rapidly paced sixty eight minutes making the most of its low budget and an army of New York types.

You will probably enjoy it far more than its modest origins might suggest.

Fri 11 Oct 2013

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

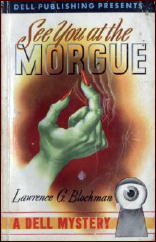

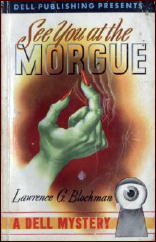

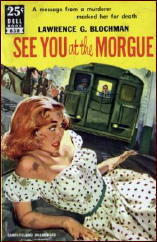

LAWRENCE G. BLOCHMAN – See You at the Morgue. Duell Sloan & Pearce, hardcover, 1941; Dell #7, no date [1943]; Dell #638, paperback, no date [1952]. Both paperbacks are mapback editions.

Vivian Sanderson is marking time working as a “phantom secretary” — those who not only take phone messages but “give out price quotations, take accident reports at night for insurance companies, accept orders.” Sanderson gets an unusual message for her cousin, Penelope Dunne, suggesting that Dunne leave town because something is going to happen to her “white-haired boy.”

The next day, Dunne’s former boyfriend, a noted playboy, is found shot to death in her apartment. Sanderson, natural!y — where else would she be in a mystery? — is on the premises when the body is discovered by her boy-friend, who most unsatisfactorily tries to cover up her presence.

Sanderson is an intelligent, level-headed female for the most part. But the author feels it necessary to make her, in a term presently making the political rounds, a “useful idiot.” Blochman has her do things that she definitely ought not, such as receive a message from someone who may be the killer and then go dashing off to make the appointment suggested. This leads to her nearly getting run over in the subway.

The best of the book, and worth reading it for, is the police-procedural part, featuring Kenneth Kilkenny, Detective First Grade. Kilkenny is an interesting character and a good investigator. It’s a pity that Blochman didn’t devote more of the novel to Kilkenny and less to the damsel-in-distress-boyfriend-somewhat-to-the-rescue theme.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 1, Winter 1988.

Bibliographic Note: Kenneth Kilenny made a second appearance in Death Walks in Marble Halls. Dell 10 Cent Edition #19, 1951. (First published in The American Magazine, September 1942.)

Thu 10 Oct 2013

REVIEWED BY MARVIN LACHMAN:

PENTHOUSE. MGM, 1933. Warner Baxter, Myrna Loy, Charles Butterworth, Mae Clarke, Phillips Holmes, C. Henry Gordon, Martha Sleeper, Nat Pendleton. Based on a story by Arthur Somers Roche serialized in Cosmopolitan. Director: W. S. Van Dyke.

A forgotten mystery writer is Arthur Somers Roche; a forgotten film is Penthouse, which was based on his story in Cosmopolitan. (In 1935 it was published in hardcover by Dodd Mead.)

Crisp!y directed by W. S. “One Take” Van Dyke in three weeks, this movie provided the breakthrough role for Myrna Loy. Not forced to play a vamp, she displayed her natural sophistication and flair for comedy so well that M-G-M cast her as Nora Charies when Van Dyke filmed The Thin Man the following year.

Also noteworthy in Penthouse are Warner Baxter as a Perry Mason type defense lawyer who does some real detecting and Nat Pendleton almost walking away with the picture with his performance as a gangster.

Penthouse is as slick as the pages on which it originally appeared, but it is fun and worth seeing.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 10, No. 1, Winter 1988.

« Previous Page — Next Page »