January 2014

Monthly Archive

Thu 9 Jan 2014

REVIEWED BY GEOFF BRADLEY:

JUDGE JOHN DEED. BBC, Series Three; 4 90 minute episodes: 27 November through 18 December 2003. Martin Shaw (Judge John Deed), Jenny Seagrove (Jo Mills), Barbara Thorn (Rita ‘Coop’ Cooper).

You may remember (but if you live in the US, probably don’t) that Deed is a pompous and arrogant judge who is a thorn in the side of the establishment because he refuses to bow to pressure from anyone, especially the government advisers who attempt to get him to toe the line on government policy. (The writer, G. F. Newman, is known for his antiestablishment views.)

I endured rather than enjoyed the previous series, but I have to confess that I quite enjoyed this one. Typically Deed gets to the bottom of the case in front of him by asking more questions than either of the two competing barristers, to their extreme annoyance.

One of the barristers in his cases always seems to be Jo Mills, his long time lover to whom he is always proposing. Sge sets the condition that he consults a therapist to confront his womanizing ways. He agrees and then rather predictably sleeps with the therapist.

This is another of those series not to be taken seriously for a moment but at times is quite fun, although I suspect the writer would want us to take it rather more seriously.

Wed 8 Jan 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

PHILIP MacDONALD – The Rasp. British hardcover: Collins, 1924. US hardcover: Dial Press, 1925. Hardcover reprints (US): Scribner’s (S.S.Van Dine Detective Library), 1929; Mason Publishing Co., 1936. Paperback reprints (US): Penguin #586, 1946; Avon G1257, 1965; Avon (Classic Crime Collection) PN268, 1970; Dover, 1979; Vintage, June 1984; Carroll & Graf, 1984.

Philip MacDonald’s 1924 mystery, The Rasp, was the first appearance of his series sleuth Anthony Gethryn. I read and enjoyed this quintessential English Country Manor Mystery and figured out whodunit by page 70, by which time

[WARNING! SPOILER ALERT!!]

one character had left tracks to the scene of the crime at the time it was committed, so she couldn’t be guilty; another character was fund clutching the murder weapon, so he couldn’t have done it; another was seen rifling through the murdered man’s desk, a fourth had his alibi exploded as a tissue of deliberate lies, and a fifth confessed to the crime – -so they must have been innocent as well.

There was, however, one character who did nothing incriminating, merely stood around expressing polite interest and helping when he could, and he … you guessed it.

[END OF WARNING AND REVIEW]

Editorial Comment: As it so happens, my review of this same book is much longer. You may find it here. But is longer better? You tell me.

Tue 7 Jan 2014

SHANNON OCORK – End of the Line. St. Martin’s, hardcover, 1981. No paperback edition.

This reads very much as it’s supposed to, which is to say like a story told by a liberated young lady working with some caution and care in a world dominated by men. T.T. (Teresa Tracy) Baldwin is an aspiring sports photographer for the New York Graphic. She also solves mysteries.

A murder occurs at a shark-hunting tournament, and it goes without saying that [from an author’s point of view] the lesson learned from the popularity of Jaws is not lost on Shannon OCork before the case is closed. There are also some missing diamonds and an antagonistic small-town cop who is solidly in a rich man’s pocket.

As a mystery, the story is sometimes a puzzler in more ways than one. Obvious questions (to the reader, at least) arc never asked, apparently never even thought of, until at length T.T. reveals she already knew the answers, far earlier than she ever let on.

From another point of view, the broken style T.T. persists in using in telling her own story adds immediacy to the first part of the narrative, and a considerable amount of fast, page-turning excitement to the finale. In between, it simply becomes hard to read.

Other than T.T., who is bright, smart-alecky, and certain to get ahead, most of the remaining characters are straight from summer stock. The ending is worth waiting for, however.

Rating: B minus

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 6, No. 3, May-June 1982 (slightly revised).

Bibliographic Notes: T.T.Baldwin had a three book career. End of the Line was preceded by Sports Freak (St. Martin’s, 1980) and followed by Hell Bent for Heaven (St. Martin’s, 1983), neither of which do I remember ever seeing. As for the author herself, she was married for twelve years to mystery writer Hillary Waugh and in 1989 wrote a book for would-be mystery writers, appropriately titled How to Write Mysteries.

Mon 6 Jan 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

GEOFFREY HOMES – Forty Whacks. William Morrow & Co., hardcover, 1941. Reprinted in paperback as Stiffs Don’t Vote, Bantam #117, 1947. Film: Warner Brothers, 1944, as Crime by Night.

Private detectives Humphrey Campbell, milk drinker and accordion player, and his boss, Oscar Morgan, who likes much stronger stuff, have left Los Angeles under some pressure and have relocated in Joaquin, California, to the distress of some people.

With the exception of threats from the city’s district attorney, business starts out well, with a request to locate Joseph Borden, pianist. Campbell, the leg man and the brain man of the agency, at least in this novel, finds Borden, who is minus one hand, which hand was chopped off by his mother-in-law, Mrs. Gertrude Peck, the publisher of the city’s only newspaper. When the mother-in-law is found, first by Borden, considerably chopped up, the police believe Borden did it in revenge.

There were, however, many other people who had no love for Mrs. Peck. In the midst of a political campaign, she had endorsed first one candidate for mayor and then another, both of them corrupt. One of the rewrite men on the newspaper said that all the employees were suspects. Her lodge, where she was killed, was as busy as an airline terminal what with people who feared or loathed her visiting just prior to her murder.

Campbell solves the case, to my complete dissatisfaction. Not one of the better investigations of Morgan and Campbell, who can be compared to Frank Gruber’s Johnny Fletcher and Sam Cragg but are not nearly as amusing.

(The title change by the paperback publisher indicates that even in 1947 the memory of Lizzie Borden had waned. Forty Whacks had that title because one of the character was named Borden and an ax was the murder weapon. The rhyme “Joseph Borden took an ax,/ Gave his mother-in-law forty whacks” keeps running through Campbell’s head. For those who may not know about the fascinating Lizzie Borden case, I highly recommend Victoria Lincoln’s A Private Disgrace: Lizzie Borden by Daylight, reprinted by International Polygonics in 1986.)

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 1, Winter 1988.

Sun 5 Jan 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

BERNIE LEE – Murder at Musket Beach. Donald A. Fine, hardcover, 1990. Worldwide Library, paperback, November 1991.

Here is an example, if one is desired, of a book that I cannot imagine will interest any fan of the old-fashioned detective story one iota. It is the first mystery adventure of a husband-and-wife sleuthing duo named Tony and Pat Pratt, and even though there is a second promised, I can promise you that I will not be reading another.

Tony Pratt is a mystery writer, Pat Pratt is a financial consultant, and together they find a body on the beach. This is the interesting part. It goes downhill from here.

There are two suspects (three if you count the mysterious behavior of the policeman investigating the case, behavior never satisfactorily explained except there does have to be some mystery in a detective story, one supposes, doesn’t there?). There is one clue, and the culprit can’t imagine how or why he managed to drop it right there next to the body.

The victim was in real estate, it is learned, a guru is trying to buy some local land upon which to build his commune, and over and over again it is carefully explained to us that this might be the reason for the murder. [WARNING: Plot Alert.] It is.

In other words, this is a mystery for the feeble-minded. It’s not the writing that is so bad; it’s the complete absence of a plot.

— Reprinted from Mystery*File 37, no date given, considerably revised.

Bibliographic Update: There were, in fact, two more books in the series: Murder Without Reservation (1991) and Murder Takes Two (1992).

Sun 5 Jan 2014

Reviewed by MIKE TOONEY:

IRONSIDE (1967-75): 8 seasons, 195 episodes. Regular cast: Raymond Burr (Ironside), Don Galloway (Det. Sgt. Ed Brown), Elizabeth Baur (Officer Fran Belding), and Don Mitchell (Mark Sanger).

If you like your TV crime dramas with complications and the rare out-of-left-field plot twist, these two episodes might fill the bill. One is yet another variation on the “caper” trope, while the other involves the venerable locked room murder theme.

“All Honorable Men.” Season 6, Episode 21 (150th). First broadcast: 8 March 1973. Guest cast: William Daniels, Fred Beir, Johnny Seven, Sandra Smith, Leonard Stone, Henry Beckman, Arthur Batanides, Regis Cordic. Writer: William Douglas Lansford. Director: Russ Mayberry.

A bank manager closes the vault and activates all the security systems; sixty-three hours later, when it’s opened, the floor is littered with safety deposit boxes, some of them having been broken open — but the rest of them and even the stacks of money in the vault lie untouched.

Everything indicates that a handful of thieves tunneled up through the vault of the floor, selectively plundered the richest deposit boxes, and made a subterranean getaway, with a helicopter waiting to take them out of the country. Every bit of forensic evidence (including geological analysis of the sand at the crime scene and aboard the abandoned chopper) points to that inescapable conclusion.

Only that’s not how it went down — nowhere near it — and, although it takes him a while, eventually Ironside figures out what really happened.

Kudos to writer Lansford (1922-2013) for coming up with a nicely gnarly caper scenario (even if he did borrow elements from Doyle’s “The Adventure of the Red-Headed League”), as well as to actor Raymond Burr (1917-93) for pulling off what was clearly a very difficult physical stunt.

“Murder by One.” Season 7, Episode 2 (154th). First broadcast: 20 September 1973. Guest cast: Mary Ure, Clu Gulager, Herb Edelman, Michael Baseleon, Dennis McCarthy, Robert Van Decar. Teleplay: David Vowell and Sy Salkowitz. Story: David Vowell. Director: Alexander Singer.

An emotionally disturbed young man is found inside a locked room, a fatal gunshot to the head. He had been undergoing psychotherapy after his parents’ divorce, and his therapist can’t be sure he hasn’t missed some warning sign presaging the tragedy. In any event, there seems to be no compelling reason not to assume he committed suicide; a slip of paper with a quotation from A Tale of Two Cities next to the body can reasonably be considered a farewell note.

But when Ironside & Co. hit the scene, several seemingly unrelated bits of evidence turn up: the fact that the gun is found 8 feet 2 inches from the body; the merest trace of a not readily recognizable substance is detected on the door’s dead bolt lock; a large rubber band is found on the floor; $5,000 in hard cash is discovered inside a phonograph album sleeve in the kid’s music collection; the man hoping to marry the young man’s mother has a criminal record and is going under an assumed name; and the “suicide” note itself has a jagged edge that, to Ironside, seems out of character, contrary to the victim’s neat and orderly lifestyle.

Ultimately Ironside will uncover a plot to make a murder look like a suicide but with the real intention of making that suicide look like a murder.

There’s also some more borrowing from Conan Doyle here, in this case “The Problem of Thor Bridge.”

Fri 3 Jan 2014

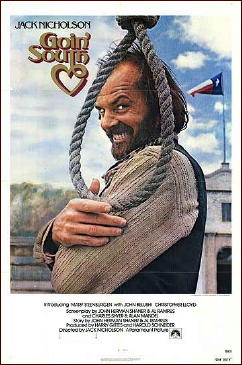

GOIN’ SOUTH. Paramount Pictures, 1978. Jack Nicholson, Mary Steenburgen, Christopher Lloyd, John Belushi, Danny DeVito, Veronica Cartwrighht, Ed Begley Jr. Director: Jack Nicholson.

Even if I told you this was a Western, you’d still know it was a comedy, just by looking at the list of people in it. The only two cast members of any consequence, however, are Nicholson and Steenbergen — the first film appearance of the latter, at the very young age of 25.

Nicholson is a horse thief, a former member of Quantrill’s Raiders, an outlaw through and through, and of no good to anyone to boot. Captured in Mexico and broght back (illegally) across the border to be hanged, he is saved from the noose at the last minute by Steenbergen’s speaking up at the last minute to say that she will parry him. (A local ordinance carried over from the Civil War, when men were scarce.)

It’s not really a husband she’s looking for, however. She has a mine on her property that needs working, and she’s desperate to find the gold she’s sure that’s there before the railroad comes in and takes over the land.

One look at Nicholson in this movie will show you just how desperate she is. He is the scruffiest looking star of a major motion picture that I can ever recall seeing. He is manical capering gnome of a man, leaping for the sheer joy of living, with a leer in every glance to sends his new wife’s way.

And Mary Steenbergen, although still young, is a quintessential “old maid,” with fussy, virginal ways, but totally in charge of the situation, until, of course, it blushingly (and inevitably) goes out of control.

The rest of the cast is there for background, nothing more, except for perhaps Veronica Cartwright, who plays the outlaw’s former love, he “first woman he ever had to pay for.” Sparks fly, misunderstandings abound, nefarious double-dealings run amuck. And for a Jack Nicholson movie, there are surprisingly few moments of enigmatic incomprehensibility. This is a funny movie, worth looking out for.

— Reprinted from Mystery*File 37, no date given, slightly revised.

Thu 2 Jan 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

MILES BURTON (Charles John Cecil Street, MC, OBE, 1884-1965) — The Secret of High Eldersham. Mystery League, US, hardcover, 1931. First published in the UK by Collins, hardcover, 1930.

I can testify that the portrayal of East Anglia in this novel is fairly accurate, at least it still was in the 1970’s. It’s a somewhat insular part of England, friendly enough on the outside, but slow to accept strangers, and like many small communities prone to suspicion of anyone and anything new. You can spend thirty years of your life their and still be a foreigner, even if they like you. Simply living there does not make you one of them.

There are certainly towns like that here as well, but it is pronounced in East Anglia — and in High Eldersham, a village of some three hundred people the insularity is particularly pronounced. A few families have intermarried until everyone is related to everyone else, and there is nothing but distrust for strangers. In High Eldersham newcomers tend to have ill fortune, they seldom stay long.

But Mr. Thorold had a long experience of strangers as tenants in East Anglia. However hardworking and conscientious they might be, however keen to promote trade, the receipts of their houses had a way of falling off until they were perforce compelled to relinquish their tenancy. And this curious distrust of strangers, common throughout East Anglia, was particularly active in remote villages like High Eldersham. Yet Dunsford had said that no local man would take the Rose and Crown, and he knew every soul in the village and for miles around.

Burton is good here showing the impact of the First World War on small English villages, both socially and economically. Still, murder is carrying it a bit far so far as local Constable Viney is concerned when he finds the publican of the Rose and Crown, Edward Whitehead, Mr. Thorold’s chosen outsider tenant, a retired sergeant of the Metropolitan Police force, stabbed to death in his chair.

The Chief Constable is by no means sure of local Superintendent Bateman’s ability to handle a murder of this sort, so against the other man’s wishes he asks for help from New Scotland Yard (the detective branch of the London Metropolitan Police, not a national police as sometimes implied in detective stories — still well through the sixties small police forces did sometimes call on the Yard for help — as is done here, and Yard investigations may lead almost anywhere in England, or the world).

Help arrives in the person of Inspector Young (whether as Burton, Waye or Rhode, his policemen tend to be efficient and capable), who enlists Constable Viney as a local expert, and handles himself quite well, but as his first few leads fail to pan out Young decides to call on a wartime friend for help.

During the war (WWI) Young frequently had dealings with the Naval Intelligence branch of the Admiralty, and in the person of a bright fellow he quite admires, Desmond Merrion (Merrion usually works with the competent Inspector Arnold, who debuts in a later adventure).

Merrion is strictly an amateur, not even classifying himself as a detective, but he’s an attractive sleuth along with his man, the capable Newbolt, and I always found him easier to take than the more stately Priestly (not to say anything against the best Priestly’s — I particularly enjoyed The Murders in Praed Street and The House on Tollard Ridge). This was the first outing for Merrion, and the best.

Charles John Cecil Street was Miles Burton, Cecil Waye (author of husband and wife private investigators Christopher and Vivienne Perin in four titles between 1931 and 1933), and John Rhode, one of the staples of the Detection Club, and creator of another great detective, the scientific sleuth Dr. Priestly.

Street was a proponent of the fair play mystery, and a spinner of solid puzzles that on occasion even developed a bit of suspense and action. Julian Symons qualifies him as being of the humdrum school. [FOOTNOTE] (Barzun and Taylor disagree in A Catalogue of Crime and review several books enthusiastically, including this one — I tend to lean toward their view), there is nothing humdrum about The Secret of High Eldersham, however.

In later years (he was still penning Priestly and Merrion novels into the early 1960‘s) Street could be frightfully humdrum to the point of boredom, and unlike Marsh, Christie, Carr, Innes, or Allingham, who all lived and kept writing longer than him, he didn’t manage to modernize much past WWII or hold on to more than a few diehard fans. He is likely best known today for his collaboration with John Dickson Carr (writing as Carter Dickson) Fatal Descent (1939 UK title Drop to His Death), written as Rhode.

Humdrum or not Street was never a bad writer, and some of the early books are highly collectable, but as I said the later books don’t offer much, and frankly for me, they read as if he was just churning it out without the inspiration or the enjoyment of his earlier work. Failing health may also have contributed to the decline. The kindest word I can think of for them is tired, but then having been prolific since the twenties (I count seventy-one Priestly novels and sixty-three Burtons between 1925 and 1961), he was entitled to tired at that point.

In addition to his prolific mystery fiction he wrote non-fiction, often dealing with international politics, and short stories, theater (unproduced), and radio plays (featuring Priestly and Inspector Jimmy Waghorn from the Priestly series). He wrote at least one memoir of his service as a gunnery officer in the First War, and one of his service in Ireland as an Intelligence officer.

That doesn’t matter here, because The Secret of High Eldersham is one of the highlights of his long career, and for my money the best of the Merrion novels. This one has a bit of everything all perfectly balanced between detection, action, and deeper mysteries than mere murder. Something old and evil is brewing in High Eldersham, and anyone who stands against it meets a terrible fate.

When Constable Viney is struck down by a mysterious illness Merrion begins to suspect a broad conspiracy at work (many of Burton’s books feature large criminal enterprises — something a bit different than the more personal murders of many of his contemporaries — not to suggest the others didn’t deal with their fair share of criminal conspiracy and even international intrigue).

It looks to me as though the High Eldersham people suspected, if they don’t actually know, that somebody about the place murdered Whitehead. If they thought it was a stranger, they’d be only too ready with information. As it is, they are convinced that the man met his death in consequence of the spell cast upon him, and the example of his fate is quite enough to induce them to hold their tongues.

There is even an unobtrusive romance for Merrion that figures neatly into the plot causing him some real consternation and anxiety and introducing Merrion to his wife to be, Mavis Owerton, daughter of local landowner Sir William, one of the suspects to Merrion’s chagrin. Burton handles the romance quite well.

Side by side they walked down through the park. The fog had descended thicker than ever, and without Mavis’s guidance Merrion would inevitably have taken the wrong path. She led him to where the dinghy was tied up, then suddenly, as he was about to step into it, she laid a hand upon his arm. “You’re not going to do anything dangerous are you?†she asked softly.

He swung round and faced her. There was a note of solicitude in her voice which made the blood run madly through his veins. Obeying a sudden impulse he caught her in his arms. She lay there for an instant, then gently disengaged herself.

Breathing one last word, “Mavis!†he stepped into the dinghy and picked up the oars. The girl’s figure faded from his eyes into the surrounding mist.

It’s a grown up romance, and doesn’t get in the way for once. Merrion’s concerns for Mavis are genuine and justified, but never descend to the silly ass behavior of some other classic sleuths in love. The Detection Club rules frowned on romance, but just about all the original members broke the rule in one book or the other. It’s Burton’s turn here.

In his early days as Rhode he was prone to the popular theme of the twenties, drug smuggling, especially cocaine. As Rhode, he even wrote a non series book more or less on thriller lines, The A.S.F. The Story of a Great Conspiracy (1924, US title The White Menace).

The drug theme raised its head in his work once in a while after that as it does here, and a nastier lot of smugglers, secretive islanders, villains, devil worshipers, and at least one murderer more sinister than East Anglia ever saw, have seldom inhabited the pages of a mystery. Deviltry is the least of it, in a very real sense, and quietly evoked by Burton, a community’s soul is at risk.

The stone was undoubtedly the altar behind which officiated the devil, the mysterious president of the coven. A glance at the sides of the stone confirmed this. It was carved with strange figures, the obscure symbols of an almost forgotten rite. A sudden horror seized him, the malign influence of this ill-omened grove.

Action, atmosphere and suspense aren’t usually the virtues you tend to associate with Burton or Rhode, but in the early Priestly novels he managed some well staged suspenseful scenes revealing the murderer, and here, taking advantage of East Anglia’s remote dramatic countryside, and his well drawn portrait of High Eldersham and its environs, he provides atmosphere, action, a chase, even a coven, a close encounter with death for Merrion and his girl, a damn good piece of mystery and detection,and there is also some well done business handling small boats. It’s a very physical as well as intellectual and disturbing investigation for Merrion.

The psychology of the thing seems fairly simple to me. The members of the coven derived a definite advantage from the ceremonies. Any one against whom they had a grudge suffered accordingly. But things were a good deal deeper than that. The real attraction was the drugs mixed in the bowl which was handed round, and the sensations they produced. It’s all pretty horrible, but there isn’t the slightest doubt that the meetings ended in an orgy of promiscuous lust, no doubt excited by some form of aphrodisiac. If you study some of the old records, you’ll find these things described in detail. H——–‘s (my annotation to save a spoiler alert) whole idea, of course, was to turn the village into a more or less criminal society …

Granted that sounds more like Dennis Wheatley than Burton or Rhode, and violates all the Detection Club rules save for Chinese chicanery (frankly that drug he describes pretty much is a ‘drug unknown to science’), but you’d have to be a pretty narrow stickler or curmudgeon to care.

This is not a tour de force, but it is perhaps the best book by one of the early masters of the form, highly entertaining, and certainly not the least dull. It is easily the fastest read by Burton or Street I know of.

But Merrion acquired property in High Eldersham, even before he was married. He bought the island which had been the scene of so many strange ceremonies, and, on the night after the purchase was completed, he and Newport went there, armed with sledge hammers, and broke the altar into little pieces, which they threw into the river.

“Reminds me of that chap in the Old Testament, sir,†remarked Newport, as he mopped his brow after his labours. “What was his name, sir?â€

“Gideon. ‘Throw down the altar of Baal that thy father hath, and cut down the grove that is by it.’ Yes, I think we’ll make a job of it, and have these trees down too. Things haven’t changed much since those days, have they?â€

The perfect end to what I consider an almost perfect book of its kind and a satisfying read both for the detective story lover and those that want a bit more accompanying it. If you read only one book by Burton or Rhode, this is the one I would suggest. I consider it one of the true highlights of the Golden Age, a masterpiece of its kind, by an old master.

[FOOTNOTE] Symons defines the Humdrum School thusly for those of you unfamiliar with the term: “Most of them (the Humdrums) came late to writing fiction, and few had much talent for it. They had some skill in constructing puzzles, nothing more, and ironically they fulfilled much better than S. S. Van Dine his dictum that the detective story properly belonged in the category of riddles or crossword puzzles. Most of the Humdrums were British, and among the best known of them were Major John Street …”. — Julian Symons, Bloody Murder.

Wed 1 Jan 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

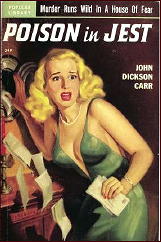

JOHN DICKSON CARR – Poison in Jest. Harper, US, hardcover, 1932. H. Hamilton, UK, hardcover, 1932. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and soft.

The magic word in describing the prose of John Dickson Carr is “atmosphere.” His stories always seem to be taking place in dark and dreary locales even when the sun is shining brightly. Let me quote from pages 28-29 of the British Penguin paperback I’ve just read:

I went into the library and stared about. It was filled with a hard brightness; one of the gas-mantles hissed slightly. Wind had begun to thrum the window-panes, so that reflections quivered in their black surfaces, and the gimcrack lace-and-velvet draperies twitched about. The plaster frescoes of the ceiling were very dirty, and the dull flowered carpet was worn in several places. […] A commonplace library. You felt, nevertheless, the presence of something leering and ugly. A vibration, a pale terror like the mist on a photographic plate.

According to Hubin, this early novel is a non-series one, but the narrator is the same Jeff Marle who assisted Henri Bencolin, the head of the Paris police, in several earlier cases. (This one takes place somewhere in Pennsylvania, and Bencolin does not appear.)

Even though Marle does his investigative best on the cae of domestic poisonings, he does not have the makings of a true Carr detective Neither does the county detective, Joe Sargent, who is called in. They see things too straight-forwardly, and the fail to see what things really mean.

It falls upon a friend of the family’s youngest daughter Virginia, an eccentric chap named Rossiter, to come upon the scene and ferret out the truth. In the grand tradition of Gideon Fell and Sir Henry Merrivale, Rossiter’s appearance makes him seem nearly potty in his behavior — but as is finally revealed, there is method in his madness. (As the saying goes.)

I don’t believe that this is one of Carr’s finer attempts at massive misdirection, as he is so prone to do, and the pace is rather stodgy and slow. I realized who had done it on page 154 of the Penguin edition (so that this won’t help you any), and there were still over 60 pages to go. (Which rather proves both points, doesn’t it?)

On the other hand, second-rate John Dickson Carr (which I”m really implying) is still more interesting to read than 90% of the work produced by anyone else who attempts the rigorous challenge of the old-fashioned fair-play detective mystery.

— Reprinted from

Mystery*File 37, no date given, very slightly revised.

Note: In the most recent edition of Crime Fiction IV, Al Hubin now lists Jeff Marle as a series character. In the other five cases in which he takes part, it was always in tandem with Henri Bencolin.

« Previous Page