March 2014

Monthly Archive

Sun 23 Mar 2014

MY FAVORITE SPY. RKO Radio Pictures, 1942. Kay Kyser, Ellen Drew, Jane Wyman, Robert Armstrong, William Demarest, Harry Babbitt, Ish Kabibble. Director: Tay Garnett.

I don’t have much to say about this movie. Either you like band leader and long-time radio star Kay Kyser in the role of a movie hero, or you don’t. His overripe meekness and exaggerated gestures of astonishment and surprise can wear on you awfully quickly.

He’s no Pee Wee Herman, though. I think of him as an early Woody Allen type, southern style. Utterly cornball, in other words, but still funny.

His orchestra plays only a minor role in this one, as Kay is asked by the army to help unroot some spies working out of the night club where he and his band are playing, The only problem is that he’s not able to tell his wife what he’s doing, and their honeymoon is constantly being interrupted. You can see what this means, and you can take it from there.

— Reprinted from

Mystery*File 37, no date given, considerably truncated and revised.

Sat 22 Mar 2014

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

MARIANNE MACDONALD – Die Once. St. Martin’s Press, hardcover, May 2003. No US paperback edition. Published in the UK by Hodder & Stoughton, hardcover, 2002.

Antiquarian book dealer Dido Hoare loses a recent but good customer in an apparent suicide. Of course, things are never what they seem, so when the suicide is investigated, Dido finds herself involved as she inventories his collection for the firm of lawyers that’s handling the estate and gets increasingly drawn into the maze the case turns into.

The book dealing is nicely integrated, as usual. The plot is somewhat too intricate (and perhaps too drawn out) to be completely involving, but this is certainly a recommended bibliomystery.

The Dido Hoare series —

1. Death’s Autograph (1996)

2. Ghost Walk (1997)

3. Smoke Screen (1999)

4. Road Kill (2000)

5. Blood Lies (2001)

6. Die Once (2002)

7. Three Monkeys (2005)

8. Faking It (2006)

Thu 20 Mar 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

BARRY PEROWNE – Raffles Revisited, The Adventures of a Famous Gentleman Crook. Harper & Row, hardcover, 1974. Hamish Hamilton, UK, hardcover, 1974.

E. W. Hornung only wrote three collections of short stories about amateur cracksman A.J. Raffles, and a disappointing novel (Mr. Justice Raffles), so in 1932 Montague Haydon, editor of the British magazine Thriller had the bright idea of continuing the character. He approached Leslie Charteris, creator of the Saint, who turned him down, and next the turned to Philip Atkey, Australian nephew of writer Bertram Atkey, who had already continued his uncle’s popular tales of cracksman Smiler Bunn.

Writing as Barry Perowne, Atkey updated Raffles to the 1930’s and involved him in adventures along the lines of the Saint and other durable desperadoes from Thriller. The writing was good, and the tales enjoyable, but the war and the paper shortage ended both Thriller and Raffles.

In 1950 Perowne had the bright idea of bringing Raffles back yet again, but this time in his original form, in short stories set in the original period and milieu. Raffles, the gentleman cricketer of the M.C.C. (Marlebone Cricket Club) and the Albany and his pal Bunny Manders were back and in the opinion of many if some of Hornung’s atmosphere and decadence are gone the writing and the plots have improved no end.

The new stories appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, The Saint Mystery Magazine, and John Bull. They were an immediate critical and popular hit. In addition Perowne gave the perpetually dumb Bunny half a brain, a device that helped the stories no end, and added Raffles sister Dinah to the mix.

The stories in Raffles Revisited are:

The Grace and Favor Crime

Raffles and Bunny foil a German spy ring, thanks to a dog that doesn’t know its master and a master who doesn’t know his dog, and Raffles is offended by a bribe.

Princess Amen

Raffles employs a mummy case to crack a safety deposit box in a bank and comes close to suffocating, save for fast thinking by the fence Ivor Kern and Bunny’s ability to read hieroglyphics.

Kismet and the Dancing Boy

Raffles plays cupid while coveting a rare chess set.

The Birthday Diamonds

In Paris Raffles finds himself cracking a safe for a Parisian policeman in front of a room full of witnesses — and still gets the swag.

The Dartmoor Hostage

A cricket game at the prison uncovers an attempt to break in to Dartmoor, and a secret that turns a profit for Raffles.

The Doctor’s Defense

On a cruise Raffles and Bunny have to aid an old classmate set up as the fall guy in an international con game involving phony diamonds.

The Gentle Wrecker

Raffles breaks his oath to never rob a house he is a guest in to steal a ship’s figurehead and unite a pair of lovers by framing an innocent man.

Six Golden Nymphs

Raffles eludes the police by setting them to solve a murder that never happened.

Man’s Meanest Crime

Raffles foils the Anniversary Thief.

The Coffee Queen Affair

Raffles meets his American compliment and aids the Knickerbocker Kid in reform and romance, all to win a wager on who will be chosen the Coffee Queen.

An Error in Curfew

Raffles postpones lifting a fortune in jade to help a houseful of young ladies named after the days of the week.

Bo Peep in the Suburbs

Raffles has to rob a safe that is only out of sight for a few minutes every day.

The Governor of Gibraltar

Raffles becomes the envoy for his old school chum the Royal Governor of Gibraltar in order to help the husband of a charming and innocent con woman escape from a heavily guarded ship carrying gold bullion.

The Riddle of Dinah Raffles

While Raffles is in Australia Bunny discovers his sister is more than blood ken to the master cracksman.

Later books in the series, Raffles of the Albany, and Raffles of the M.C.C. add a new twist to the stories with Raffles meeting historical personages like Winston Churchill (“The Baffling of Oom Paul”), Conan Doyle (“The Victory Match”), Oscar Wilde (“Dinah Raffles and Oscar Wilde”), and P.G. Wodehouse (“The Graves of Acadame”) among others.

With the possible exception of August Dereleth’s Solar Pons stories, the Raffles pastiche are unique in that they established their own fan base beyond the original stories. I’ll confess I find them superior to Hornung in terms of plot and writing, and believe they stand alone as some of the most entertaining stories of their kind ever penned.

Perowne is not the only author to continue Raffles adventures. John Kendrick Bangs wrote a series featuring Mrs. Raffles and another with the son of Sherlock Holmes and Raffles daughter, Raffles Holmes. Graham Greene penned a play, The Return of A.J. Raffles, and Alan Moore recently included Raffles as one of The League of Extraordinary Gentleman graphic novels. David Fletcher, creator of the British television series Raffles with Anthony Valentine wrote a novelization of the eleven stories in the series.

The Perowne stories are well worth discovering even if you don’t care for the originals by Hornung. Perowne’s version of Raffles and Bunny are a charming pair of rogues who manage the balancing act of a career in crime while never endangering their standing as English Gentlemen or Raffle’s standing as England’s finest cricketer. How they manage that feat is a constant source of entertainment in probably the finest series of pastiche ever written.

Wed 19 Mar 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

PHILIP MacDONALD – Something to Hide. Doubleday Crime Club, US, hardcover, 1952. No paperback edition. Published in the UK as Fingers of Fear: Collins, hardcover, 1953. A “Queen’s Quorum” title.

This collection comprises two novellas and four short stories, all exceptionally well done. Two of the stories display the abilities of Doctor Alcazar, MacDonald’s “clairvoyant” detective.

In “The Green-and-Gold String,” Alacazar is at his tent at the carnival and reads the future — “General Reading–50 cents. Special Delineation–$1.00†— of a lady’s maid, who is murdered several days later. Her employer offers a reward of $5000, and Alcazar can’t resist the “easy” money. Alcazar is a character, of course, but a superb psychologist and bluffer, and he traps the murderer into a confession.

In the second story about Alcazar, “Something to Hide,” he and companion, the carnival’s former Weight-Guesser, are down on their luck. Their former client knows a rich woman with a problem, but how is Alcazar to know what the problem is? No one needs to tell a clairvoyant anything; he should already know it. As Avvie says:

“Pinkertons! The Bass-Ackwards Detective Agency Inc. — No Crime Necessary — All We Need’s The Clues!” “Very funny,” said Doctor Alcazar. “Quite amusing.”

“The Wood-for-the-Trees” has Anthony Gethryn returning to England from the US in the summer of ’36. He is delivering a letter from a Personage of Extreme Importance in the US to another P.O.E.I. in England. The area to which he is delivering the letter has recently had two murders by, ostensibly, an obvious maniac.

A third occurs while Gethryn is there, and he quite frankly admits that a motiveless crime is best handled by “routine politico-military methods.” Something his son says on his return home and wifely suspicions, however, put him on to the murderer.

“Malice Domestic” deals with a husband who is being given poison, most probably by his wife, and the “happy” ending, or at least happy if you’re the murderer.

“Love Lies Bleeding” is something of a horror story. How does Cyprian Morse, having killed a young lady in hot blood after she tries to seduce him — Cyprian is CD all of the way, you see — manage to be freed after telling a quite implausible tale of how the murder happened? A fairly evident ending, but nonetheless a powerful story.

Finally, “The Fingers of Fear” deals with a child molester and murderer. After he has presumably been apprehended, Lieutenant (acting Captain) J. Connor, the man who arrested him, begins to have doubts, doubts that are reinforced by his wife. Connor and his wife begin their own investigation.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 1, Winter 1988.

Tue 18 Mar 2014

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

THE MARKET OF VAIN DESIRE. Triangle, 1916. H. B. Warner, Clara Williams, Charles Miller, Gertrude Claire, Hutton. Story: C. Gardner Sullivan. Director: Reginald Barker. Shown at Cinefest 26, Syracuse NY, March 2006.

Mrs. Badgely (Gertrude Claire) has engineered a marriage between her reluctant daughter Helen (Clara Williams) and the too smooth and obviously villainous Count Bernard d’Montaigne (Charles Miller). (You have to suspect that he’s not all he seems to be since no true French aristocrat would drop the “e” in d(e) Montaigne.)

Pastor John Armstrong (H. B. Warner, warming up for his role as the Christ in DeMille’s King of Kings), upset by the blatant insincerity of the arranged marriage, preaches a sermon in which he compares the “selling” of a daughter to a woman selling her body on the street, bringing home this message with the introduction of a streetwalker (Leona Hutton) into the service.

The congregation is horrified and when Helen’s father calls off the engagement, the “Count” confronts and assaults the minister. When the fake aristocrat is exposed, the members of the congregation are reconciled with their pastor, and he and Helen, realizing that they love one another, pledge their troth.

I like a meaty melodrama, and this heady mix of religion, prostitution and social climbing was to my taste. I wasn’t raised a Southern Baptist for nothing. The moral lessons I absorbed in countless sermons and bible classes still resonate in the proper setting and with the right material.

I noted with some surprise that C. Gardner Sullivan was both the author of the scenario for Hairpins [reviewed here ] and of the story for the very dissimilar Market.

Mon 17 Mar 2014

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Health issues, tax chores, snow — I have more excuses for the lateness of my latest column than a toad has warts. This month we cross the Atlantic and resurrect my impressions of some British whodunits I read back in the late Sixties and Seventies. I didn’t read them in chronological order but I’ll arrange them that way for the column.

Leslie Charteris’s Meet—the Tiger! (Ward Lock 1928, Doubleday Crime Club 1929) is just as cornily melodramatic as the title suggests, featuring a pure heroine whom the mustachioed leering villain tries to force into marriage and a hidden mastermind captaining a clutch of super-crooks.

What saves this book from the graveyard of worthless imitations of Edgar Wallace is that its hero, appearing for the first time, is a daring young swashbuckler christened Simon Templar but better known as The Saint.

Simon’s two-front war against Scotland Yard and the super-crooks for the prize of a fortune in gold hidden somewhere around a Devonshire village lacks the gleeful outrageousness in plotting, prose and people-drawing that was soon to become the hallmark of the Saint Saga, but its historic interest is hard to deny.

H.C. Bailey’s Garstons (Methuen, 1930; U.S. title The Garston Murder Case, Doubleday Crime Club 1930) is set on the palatial estate of the munitions-manufacturing Garston family and in the surrounding towns and villages.

The 20-year-old disappearance of an obscure chemist whose formulas the Garstons may have stolen, the theft of some cheap jewelry from the fiancée of a long-dead Garston scion, and the strangulation of the ailing matriarch in a dark archway of the family castle, blend into a neat problem for psalm-spouting criminal lawyer Joshua Clunk.

Bailey here uses the multi-viewpoint approach, putting us inside the heads of Clunk, his Scotland Yard antagonist Superintendent Bell (who will be familiar to readers of the author’s Reggie Fortune stories), a local inspector, a Jane Eyre-like nurse, and the young student who falls for her in the chaste old-fashioned way.

The interplay of each one’s knowledge with the others’, some fine scenes of interrogation and recapitulation, and a wealth of details of time and place and history and geography combine to make this long, slow, carefully constructed work a model British detective novel of the Golden Age.

George Bellairs’ Death of a Busybody (John Gifford 1942, Macmillan 1943) finds genial Inspector Littlejohn paying a wartime visit to the town of Hilary Magna to find out who drowned the village voyeur in the vicar’s cesspool.

He encounters some amusing bucolic suspects and his investigation moves more briskly than is customary in English whodunits, but the climax is clumsily structured, the solution is reached purely by legwork, and the culprit is obvious to readers (though not to the supposedly seasoned officials) as soon as he offers his alibi.

A sharp incidental picture of a country hamlet in wartime is the highlight of this all too average specimen.

In Harry Carmichael’s Put Out That Star (Collins, 1957; U.S. title Into Thin Air, Doubleday Crime Club 1958) we follow insurance investigator John Piper as he looks into the disappearance of a glamorous British movie queen from a fashionable London hotel.

Eventually he discovers how, who and why, but the only readers who won’t have tumbled to the truth a hundred pages ahead of Piper are those who are completely innocent of the hoariest cliche denouement in English mystery fiction.

Carmichael also manages to slip in the most hackneyed American climax in the genre and to leave several huge holes in the plot. Quite an achievement, yes?

A Murder of Quality (Gollancz 1962, Walker 1962) casts John LeCarre’s ex-spy George Smiley in the unusual role of private sleuth, invading Dorsetshire’s posh and snobby Carne School in order to look into the fatal bludgeoning of an instructor’s wife shortly after she stated that she was afraid her husband was trying to kill her.

Smiley pokes into the animosities between townies and gownies and between the Anglicans and the Baptists without neglecting physical clues like the piece of bloody coaxial cable and the altered examination paper, but LeCarre never clarifies how Smiley reached his solution nor what the murderer’s plan was.

However, the confused plot is balanced by fine evocations of scene and character, including two of the bitchiest females I’ve ever encountered in a whodunit.

John Creasey’s The Depths (Hodder & Stoughton 1963, Walker 1967) isn’t really a mystery but a blend of philosophy, SF and suspense that’s typical of his postwar novels about Dr. Palfrey and the international organization Z5.

This account of Palfrey’s war against the mad-scientist ruler of an undersea kingdom who’s discovered the secret of prolonging life indefinitely and can also create tidal waves powerful enough to destroy any ship or seacoast in the world crawls at snail speed and bulges with plot holes.

But it’s worth reading for a few fine character sketches — notably that of another doctor who slowly discovers a humanistic conscience — and especially for the climax where Creasey evokes the moral nightmare of politico-military decision-making in today’s world. The implied value judgments may rouse readers to fury but very few of the tough questions are evaded in this early specimen of the techno-thriller.

Douglas Clark’s Deadly Pattern (Cassell 1970, Stein & Day 1970) is a plodding and drearily written quasi-procedural in which snobbish Detective Chief Inspector George Masters and his three Scotland Yard subordinates are dispatched to a tiny coastal town to investigate the almost simultaneous disappearances of five drab middle-class women.

When four of them are found buried by the seashore, Masters and company crawl into action, taking 169 pages to uncover a psychotic killer whose identity should be apparent to every reader by page 30.

Sun 16 Mar 2014

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

ALEX GORDON – The Cipher. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 1961. Grove Press, paperback, 1961. Pyramid X-1483, paperback, 1966.

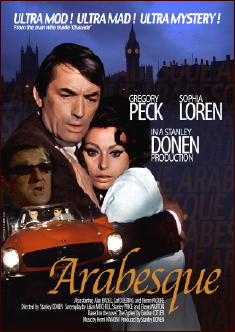

ARABESQUE. Universal, 1966. Gregory Peck, Sophia Loren, with Alan Badel, Kieron Moore, Carl Duering, John Merivale, Duncan Lamont, George Coulouris. Based on the book The Cipher, by Alex Gordon. Director: Stanley Donen.

Alex Gordon’s The Cipher is a polite little mystery that tiptoes into Graham Greene country now and again on its gentle way to wherever it’s going.

Philip Hoag carries the tale, a reedy, asthmatic professor of middle-eastern anthropology, bullied by his superiors at college, handymen in his apartment building, and lately deserted by his wife and child — the sort of burnt-out case Greene evoked so well, here trotted out to play an unlikely part in a scheme of international intrigue and all that sort of thing.

Hoag finds himself suborned by a corpulent Arabian tycoon named Beshraavi (who could as easily been called Sydney Greenstreet) to decipher an inscription that Beshraavi may have murdered to get. The money’s good and Hoag is easy to push around, so he soon finds himself working on it—and just as quickly finds himself warned by Beshraavi’s perky little college-girl niece that finishing the job will almost certainly prove hazardous to his health.

We turn another couple of pages and Hoag is running for his life, trying to escape the Arab’s minions, prevent an assassination and protect his own wife and child.

Given this premise, it’s surprising how little action there actually is in The Cipher, as Hoag spends most of the book trying to figure out the people involved and maneuver his way around and through a web of tangled motivations and petty personal problems.

I think I know what author Gordon was trying to do though: As Hoag moves through various strata of society and begins to understand the personalities involved, he grows increasingly adept at persuading, manipulating and even bullying on his own part, and The Cipher becomes less an action story and more about the growth of his character.

And if Gordon never quite achieves the heights of Graham Greene or Eric Ambler, one has to give him marks for trying and note that the last few chapters generate some real suspense, capped off with a genuinely amusing curtain line.

When this was turned into a movie, they credited Gordon under his real name (Gordon Cotler, a busy screenwriter in his day) and changed the title to Arabesque, but this was only the beginning of the cheerful havoc wreaked on The Cipher by director Stanley Donen and a phalanx of writers that included Peter (Charade) Stone. To play the book’s frail asthmatic professor with thinning blonde hair, Donen naturally turned to Gregory Peck, who transforms the character into that staple of the Movies: a healthy, handsome, straight guy with no visible neuroses who has somehow grown into early middle age without ever getting married.

The gluttonous Arab is played by slender British actor Alan Badel (who infuses the part with a genial, easy-going nastiness, coupled with a neat touch of fetishism) and the perky little niece becomes Sophia Loren, a fine actress but one to whom the words “perky†and especially “little†simply do not apply.

With this as a start, Donen and his crew proceed to run through Gordon’s gentle book with a mulching mower, filling the movie with witty quips, furious fight scenes and hairbreadth escapes reminiscent of the old serials while cinematographer Christopher Challis (best remembered for Tales of Hoffman) shoots everything at odd camera angles, through chandeliers, from inside fish tanks, reflected in mirrors or from underneath rugs, giving the film a baroque look that more than justifies the title.

Somewhere in all this is a story about a cipher to be decoded, a planned assassination and a few other bits and pieces from Gordon’s book that pop up from time to time like frightened squirrels looking fearfully about the turbulent surroundings, ready to flee at once. But it’s all so much fun and (like Loren herself) so easy to look at that one easily forgives the excesses to relax and enjoy a simple fun movie.

Fri 14 Mar 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

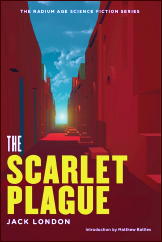

JACK LONDON – The Scarlet Plague. HiLo Books, US, softcover, 2012. (The Radium Age Science Fiction Series 1.) Introduction by Matthew Battles. Originally published in London Magazine in 1912. This edition follows the text of the hardcover edition published by The Macmillan Company, also 1912.

Although perhaps best known for his 1903 novel, The Call of the Wild and his 1908 version of the short story, “To Build a Fire,†San Francisco native Jack London also wrote proto-science fiction and dystopian literature. London’s 1912 novella The Scarlet Plague, reprinted in paperback in 2012 — the first in HiLo Books’ The Radium Age Science Fiction Series—remains a lesser known, but still culturally significant, work of early science fiction.

Set in the scenic Bay Area in 2073, The Scarlet Plague is best categorized a work of post-apocalyptic literature. Sixty years prior, a plague of unknown origin wiped out most of the population. Survivors are scant. Civilization has fallen. What’s left of mankind has been reduced to what London depicts as a state of barbarism and savagery.

There is one man, however, who remembers — with great sadness it should be noted — the era before civilization’s fall. Enter Professor James Howard Smith, a professor of English literature at the University of California-Berkeley. The novella centers around the elderly Smith (known simply as “Granserâ€) recounting the emergence of the scarlet plague and its destructive impact on humanity. He tells his primitive grandsons what life was like before the plague and how the post-apocalyptic tribal society in which they now live was formed.

London’s vision of civilization’s decline, illuminated by Granser’s story, is both intriguing and one that has been recast in myriad forms by different authors. Think Stephen King in The Stand. (Also, substitute zombies for the plague and the fundamentals of the story could still work.)

That isn’t to say that London’s novella is simply an adventure or proto-zombie story. There is a definite philosophical meaning to be found within the work. As Matthew Battles aptly notes in his Introduction, London’s work resounds with echoes of the 18th-century Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico’s cyclical interpretation of History. Toward the end, Granser tells his grandsons that eventually, civilization will be reborn, but that it too shall fall.

Just as the old civilization passed, so will the new. It may take fifty thousands years to build, but it will pass. All things pass. Only remain cosmic force and matter, ever in flux, ever acting and reacting and realizing the eternal types — the priest, the soldier, and the king. [Page 126]

Strong stuff. It’s unfortunate, then, that London chose the weak narrative device of a character telling a tale to semi-eager listeners. Also, one wishes London showed why Granser was immune to the plague or at least potentially hinted at an explanation. But perhaps London’s point was that History’s path is an incredibly random one.

The Scarlet Plague remains a worthwhile, albeit quick, read. That said, it’s difficult to imagine that a publisher would consider publishing such a work today. Nevertheless, the novella provides the contemporary reader with a greater understanding of London’s worldview and how he envisioned the class system in the United States might look in 2013.

In conclusion, The Scarlet Plague is a chilling reminder that all that mankind has accomplished in the name of technology could one day disappear. A hundred years have elapsed since London’s work was published. Science fiction has not yet tired of contemplating civilization’s fall and asking the question: what then? Maybe it never will.

Thu 13 Mar 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

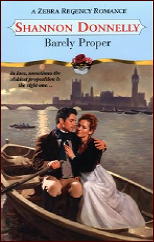

SHANNON DONNELLY – Barely Proper. Zebra, paperback original. First printing, December 2003. Cool Gus Publishing, softcover, October 2013.

On the surface, this is nothing more than just another Regency romance. When you investigate, however, you will find that there is a murder committed in Chapter One – a duel at dawn in which the second party arrives early and finds the first party had arrived even earlier, and he is already dead.

Found holding the murder weapon in his hand, Terrance Winslow [the party of the second part] makes his escape, but not without fracturing his leg in the attempt. He is found by Sylvain Harwood, whom he has known since childhood. No longer the thin and gawky girl he once knew, she is now somehow different. Her figure is different. She has attractive curves that somehow were not there before.

Aha, you say. When it gets down to it, this is just another Regency romance. Well, yes and no. While the “solving the mystery†aspect is definitely mired in second place, neither do all Regency romances have a Bow Street Runner as a significant (if not prominent) character, and this one does – although acting largely in his own interests – mixed in with the usual misunderstandings and other romantic pitfalls so intricately inherent in the genre.

One other comment. Regency romances all took place in England, more or less in the ten-year-period between 1811 and 1820. If you took all of the Regencies ever written and published and tried to fit them all into that one tiny sliver of time, you’d never be able to do it.

[UPDATE] 03-13-14. In one way this review, in case you may be wondering, is yes, a filler while I spend a bigger chunk of my spare time getting IRS material ready to take to our accountant on Monday. On the other hand, the novel is a mystery, as I was careful to point out when I originally wrote the review.

What I don’t remember is why I read the book in the first place. I may have come across the book at a local library sale and before offering it for sale on Amazon, I’m guessing, the blurb on the back cover may have tempted me into giving it a try.

The category of Regency romances, per se, is dead. They were extremely common at one time beginning with Georgette Heyer reprints from Ace back in the 1960s or so. Why did the category die out? The simple answer is that the books were too chaste. See David Vineyard’s review of the Lora Leigh book posted here a week or so ago. Sizzlers like this are what readers of romance fiction seem to want now, to the exclusion of all else.

Wed 12 Mar 2014

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

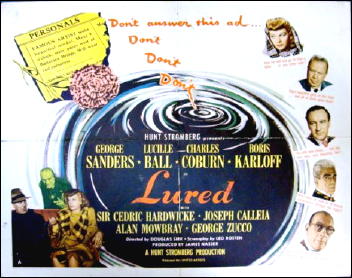

LURED. United Artists, 1947. George Sanders. Lucille Ball, Charles Coburn. Sir Cedric Hardwicke, Boris Karloff, George Zucco, Joseph Calleia, Alan Mowbray, Robert Coote, Alan Napier. Screenplay by Leo Rosten. Story by Jacques Companéez, Simon Gantillion & Ernest Neuville. Directed by Douglas Sirk.

Douglas Sirk’s name is primarily associated with a series of glossy brilliant soap operas made in the 1950’s such as Written on the Wind, Tarnished Angels, and All That Heaven Allows, but before turning to these lush technicolor films the European Sirk produced three droll crime films: A Scandal in Paris with George Sanders as the thief turned policeman Eugene Francois Vidocq, Summer Smoke again with George Sanders and based on Anton Chekhov’s short novel The Shooting Party, and this, Lured.

The setting is post war London where the city is paralyzed by a series of murders of young women who all answered ads in the agony column of the London Times. After each killing the murderer sends a taunting poem to Scotland Yard daring them to catch him.

Inspector Harley Temple (Charles Coburn) is in a bad mood, because so far his investigation is getting nowhere, but when he meets Sandra Carpenter (Lucille Ball), the best friend of the latest victim, he has a bright idea. What if he turned the killers method of meeting his victims against him — set a trap for him with an attractive lure — and Sandra Carpenter a smart savvy American showgirl is the perfect lure.

George Zucco is the sardonic Officer Barrett assigned as Ball’s bodyguard. She will answer the ads, meet the men who sent them, and when the killer shows his hand Barrett will pounce.

After a couple of false starts, including a fine performance by Boris Karloff as a mad dress designer, they get their first real lead, Robert Fleming, a nightclub producer and impresario whose shows Ball had been trying to get into from the beginning.

But the game is complicated when Ball starts to fall for Sanders even though she has been warned by his business partner Julian Wilde (Sir Cedric Hardwicke), and he fits the bill of the killer all too well.

Ball resigns, convinced Sanders is innocent, but then a turn convinces her she was wrong, he is arrested, and then the real killer makes his move …

Coburn is a pleasure as the Inspector, and Zucco, fine in a rare comic performance, is a droll delight. In fact Zucco comes near stealing every scene he appears in, which is no easy thing because Ball is not only beautiful, but holds the screen with real star power.

If you ever thought George Sanders would be an odd match for Lucille Ball you’d be wrong. They are a perfectly matched romantic pair here, and Sirk builds some real suspense because even cast as the hero Sanders had played so many villains it was no sure thing which side he would turn out to be on.

The word that best defines this movie is droll. The screenplay by Leo Rosten is sharp (Dark Corner, Captain Newman MD, Where Danger Lives, Silky …), and the cast is a fine collection of character actors from the Hollywood Raj. It’s the kind of film where the smallest performance is perfectly timed and delivered.

Comedy, romance, and suspense are expertly blended in this one. Sirk’s notable cinematic eye never lets the viewer down and a fine cast are all at their best.

Still even among that fine cast. Lucille Ball and George Zucco are standouts and even if it is little more than a bit, it is nice to see Boris Karloff in a first class production having a bit of fun on screen.

These three films were impossible to see for many years, but A Scandal in Paris and Lured have been issued in handsome DVD’s from Kino Video and both have played on TCM. Summer Storm was released on DVD by VCI in 2009 and is worth obtaining since it contains fine performances by Sanders and Edward Everett Horton as nineteenth century Russian noblemen caught up in a crime of passion.

« Previous Page — Next Page »