June 2014

Monthly Archive

Thu 12 Jun 2014

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

GUY COMPTON – Disguise for a Dead Gentleman. John Long, UK, hardcover, 1964. No US edition.

Not a happy one is the life of the confidence man, particularly one as inept as Graham Boyce. Hating his brother and embittered at not having attended what would appear to be a second-class public school, Boyce is planning to impersonate his brother at the school’s centenary celebration and sell some worthless stock to one of the old boys.

Unfortunately, Boyce did not know that his accomplice, whom he asked to take up with any graduate of the school in order to be invited to the ceremonies, would choose Ben Anderson, the best friend of Boyce’s brother at the school, mystery writer, and detective manqué . After Anderson arrives for the celebration, two deaths occur at the school.

As I read this book I had the feeling that Compton was a good writer who could — and really should — have done better for his characters and his plot. Though the novel does leave some dissatisfaction, I would be willing to try another of Compton’s works.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

The Ben Anderson series —

Too Many Murderers. Long, 1962.

Medium for Murder. Long, 1963.

Dead on Cue. Long, 1964.

Disguise for a Dead Gentleman. Long, 1964.

High Tide for Hanging.Long, 1965.

Bibliographic Note: While I was getting this review ready to post, I discovered that Guy Compton has to be a lot better known to science fiction fans than he is to mystery fans. Most of his SF novels were as by D. G. Compton, many of them published in the US as paperbacks.

Thu 12 Jun 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

MATTHEW BRANTON – House of Whacks. Bloomsbury, paperback, April 1999.

House of Whacks got some poor reviews on the net, mostly, I think, from reviewers who were either turned off by the cover, or turned on by it and then disappointed by the contents. Both camps missed the point of a book I found witty, suspenseful and deeply moving at times.

The story opens in Chicago, 1950, where Susan, an aspiring chorus girl, is making ends meet [insert joke] by posing for bondage photos. Branton wisely plays this for character rather than titillation. Also he seems to have researched the mail-order kinky porn business of that day pretty thoroughly, and he injects just enough detail to make it happen for the reader.

We quickly shift however, to an unnamed first-person narrator in another part of town who turns out to be a fifty year old woman dying of cancer, wrapping up her publishing business (she has a dozen writers working for her under one pen name) and reflecting with wry humor on her past (“…we gazed at each other with eyes as clear and innocent as a couple of Florida real estate brokers.â€) as a Hollywood Screenwriter. Again, I was impressed with the author’s knowledge of the movie scene and small-time mid-century publishing, and with his skill at evoking them.

In short order, the Mob moves in on the porno racket, Susan meets a nice young mobster with visions of moving the Mafia into more legitimate enterprises because that’s where the money is, and the nameless narrator starts hatching plans for a big-time heist that will leave her dead and her unemployed ghost-writers well-off for life.

Author Branton handles these disparate elements (and several more) with a sure hand. He seems well-steeped in the movie business, Mob politics, publishing and slow death, and he moves the story along quickly, with just enough detail to ground it in reality (for Fiction, that is) but he’s not afraid to sit back and indulge his characters in some genuine emotion.

The narrator makes her case for not getting cancer treatment in a scene that actually echoed things I’ve heard from others in the same situation. And her last meeting with her estranged ex-husband rang so heart-wrenchingly true that I forgot all about the Heist coming up just a few pages away.

The result may be a bit surreal for some tastes, but I found House of Whacks just off-the-wall enough to make a fast and fun read. Don’t know if I’ll seek out any more by Branton, but I’ll definitely remember this one.

Wed 11 Jun 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

A Review by MIKE TOONEY:

EDWARD D. HOCH – Nothing Is Impossible: Further Problems of Dr. Sam Hawthorne. Crippen & Landru, 2014. Introduction by Janet Hutchings. Collection: 15 stories from EQMM.

For Edward D. Hoch (1930-2008), mysteries were primarily about plot, with characterization necessarily taking second place. The knottiest kind of mystery plot has always been the “locked room” or “impossible crime” story, which of necessity calls for more than the usual amount of cerebration on the parts of both the writer and the reader, who is expected to participate in the “game” of “howdunnit” set up by the author.

During his career, Hoch outdid even the grand master of the locked room mystery, John Dickson Carr, in the number and variety of his plots, churning out these brainbusters on a production line basis.

Hoch had several series characters threading their way through his nearly one thousand short stories, among them Ben Snow, Simon Ark, Rand, Captain Leopold, Nick Velvet, and Dr. Sam Hawthorne. It was in the stories of that last worthy, a New England general practitioner, according to Janet Hutchings (Hoch’s editor at Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, EQMM) in her introduction, that “one finds some of the best Hoch plots, perhaps because he liked to save the most difficult kind of puzzle, that of the locked room, for his country doctor.”

Hutchings contrasts Dr. Sam with one of Agatha Christie’s series characters:

“… unlike Miss Marple [of St. Mary Mead], Dr. Sam Hawthorne is not primarily an observer of his town [Northmont] — he’s an active participant in all that goes on…

“As a young single doctor, Dr. Sam is involved in all kinds of relationships — personal, professional, and civic — with characters who turn out to be suspects, victims, and witnesses. He has a stake in what happens that goes beyond achieving justice, and his supporting characters become more important, as the series progresses, than they ever could be were his primary role that of observer.”

Thus Hoch was able “to create a milieu that readers could look forward to returning to again and again.” His entire series of Dr. Sam stories would begin in 1922 (the Roaring Twenties), pass through the Depression Thirties, and end (due to his death) in 1944 (the War Years), with the ones in this collection covering the period from early 1932 to late 1936.

If you like impossible crime stories that are puzzling without being disappointing in their solutions then Edward D. Hoch’s Dr. Sam Hawthorne stories are a good place to go. Unless you’ve collected just about every issue of EQMM since 1974, however, it’s unlikely you’ll have the complete series, which is why you’d do well to get this book — and the two previous Dr. Sam collections issued by Douglas Greene’s fine publishing house, Crippen & Landru.

— NOTE: A slightly different version of this article appeared on The American Culture website.

Wed 11 Jun 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

THE GIANT BEHEMOTH. Allied Artists Pictures, 1959. Gene Evans, André Morell, John Turner, Leigh Madison, Jack MacGowran, Maurice Kaufmann, Henri Vidon. Directors: Douglas Hickox & Eugène Lourié.

The Giant Behemoth is an America-British science fiction/horror film starring Gene Evans (who appeared in several Samuel Fuller films and in Richard Fleischer’s Armored Car Robbery, which I reviewed here) and André Morrell (Quatermass and the Pit).

The two actors portray scientists tasked with stopping a giant radioactive dinosaur from reeking havoc on England. Think Godzilla transported to Cornwall and London and you’ll have a pretty good idea what this film is all about.

That’s not to say it’s simply a throwaway creature feature with amateurish acting and even worse special effects. It’s not. Ukrainian-born director Eugène Lourié, who had worked as a production/set designer for such directors as Jean Renoir, Max Ophüls, and Samuel Fuller, clearly put care into the project. Indeed, while no cinematic masterpiece or a classic worthy of academic scholarship, The Giant Behemoth is actually a solid 1950s sci-fi film, one that showcases the fact that worries about the effects of atomic testing were hardly limited to Japan.

The plot is about as straightforward as you would expect. Dead radioactive fish wash up on the Cornwall beach and American marine biologist Steve Karnes (Evans) is on the case. He partners up with British scientist, Professor James Bickford (Morell) to figure out what is going on.

It turns out there’s a giant Paleosaurus on the loose. Oh, and it’s radioactive too. (And why wouldn’t it be?) The two men work with the British military to stop the behemoth, but not before the growling giant lizard stomps around London a bit, wrecking a power station and picking up a car and dumping it in the Thames.

The film can definitely feel dated at times. It takes suspension of disbelief to fully appreciate the film for what it is, namely a better than average monster movie. The movie neither goes for cheap thrills, nor demonstrates implicit contempt for its audience. Slow moving at times, The Giant Behemoth admirably avoids the stilted, laughably amateurish acting that plagued too many of the creature features of that era. Both Evans and Morell appear to take their roles seriously. The story’s not much, but then again it doesn’t need to be.

By far, the weakest aspect of the film is that it’s so obviously a knockoff or, if one is feeling charitable, an homage, to Godzilla. And as in the original Japanese version, we don’t see much of the creature for the first thirty minutes or so. It’s in the ocean somewhere doing whatever dying radioactive dinosaurs do. We’re supposedly just waiting in suspense for the guy to show up. Problem is: in The Giant Behemoth, the oversized angry dinosaur takes a bit too long to appear on the screen in its full glory.

The movie does, however, succeed in having some great moments. While the special effects are, in many ways, completely antiquated, there are a couple of scenes in which the dinosaur is lurking about London that just look just fabulous in crisp black and white. I’ll take those over most lavish and expensive computer graphics any day.

I wouldn’t call The Giant Behemoth a great film by any stretch of the imagination. But, provided you know what you’re getting yourself into, that doesn’t stop it from being a surprisingly enjoyable one.

Tue 10 Jun 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

LOUIS BAYARD – The Black Tower. William Morrow, hardcover, August 2008. Harper Perennial, paperback, 2009.

“We never solve a damn thing really. We just make more questions.â€

Eugene Francois Vidocq remains one of the most illusive and fascinating men in history. Convict, thief, fence, police spy, master of disguise, founder of the Surete, the first modern detective force, bestselling author, the first private detective, forensic pioneer in ballistics, fingerprints, and footprints, a man who escaped from every major penal institution in France, and the model for such literary giants as Poe’s Dupin, Balzac’s Vautrin, both Hugo’s Jean Valjean and Javert, and in spirit Sherlock Holmes.

He was gargantuan in size, appetites, genius, and ego. But he has always remained elusive in fiction, a figure so outlandish that the truth about him is too fictional to be believed or conveyed without testing the readers willing suspension of disbelief.

In Douglas Sirk’s film A Scandal in Paris with George Sanders as Vidocq they had to tone down the man’s character considerably, because no audience would have believed the truth.

In The Black Tower Louis Bayard has corrected that problem, giving us not only Vidocq in his full glory, but a mystery worthy of him, the hunt for the true fate of the dauphin, the heir to the throne of France — Louis Charles, Louis the Seventeenth, the child of Louis Sixteenth and Marie Antoinette — the lost king.

It’s a mystery that has resonated since the early half of the 19th Century. What happened to the ailing child imprisoned in the infamous black tower apart from his family, and doomed to die by the fanaticism of the French Revolution, the Jacobins, and the Terror? Other novels have dealt with it (Dennis Wheatley’s Roger Brook novel The Man Who Would Be King) and much non-fiction as well, but the questions are unanswered and likely remain so.

That hasn’t stopped Louis Bayard (Mister Timothy, The Pale Blue Eye) from weaving a magical literary thriller out of a spider silk of questions, legend, rumor, history, and Vidocq himself, one of the most fascinating men of his age. In addition to its other qualities it is also one other thing, a damn good detective story, featuring the world’s first detective.

It is 1818 and France, still reeling from the Revolution, Napoleon, and Waterloo, is in the midst of the Restoration of the throne upon which sits a new king. In the Paris of this turbulent time is one Hector Carpentier, a medical student languishing in his mother’s home, and about to find himself drawn into one of the great unsolved mysteries of all time.

It all begins when Vidocq, in disguise, shows up on Hector’s doorstep with a question, who was Monsieur Leblanc (surely a nod to the creator of Arsene Lupin, another Vidocq figure), the man murdered on the way to Hector’s home. Hector has no idea, nor any suspicion that he is being drawn into conspiracy from the past and the present that is as deadly now as it was then.

… if I had to write up my life I don’t think I could start with all the usual genuflections … No, I’d have to start with Vidocq. And maybe end with him, too.

Though the mystery is compelling, the characters lively, and the setting superbly drawn everything in the book falls beneath Vidocq, a figure whose shadow at times seems to dominate all of France. Bayard’s portrait of him is one of the books great pleasures, his vivid descriptions of the man’s moods and styles forms a fascinating and vivid portrait of one of those historical figures who would have to have been invented if he didn’t really exist.

The mystery grows deeper: there is the Duchesse d’Anguoleme, the dauphin’s sister, who survived the Terror but feels guilt about abandoning the young Louis and her mother; the Baroness de Preval, widow of the Austrian ambassador who begins the hunt for the dauphin and who has secrets of her own, the new king of France who is willing to kill to keep his throne; Charles Rapskeller, a young man who may well be Louis; Herbaux the assassin; and three men, one of them Hector’s father, who took pity on a sick child held in a block tower and now from the grave may restore the rightful king of France.

There seems a new twist or mystery at every turn. Hector and Vidocq play each other each for their own goals while establishing a deep friendship, as secrets are revealed that turn the very tide of history, for no one is more anxious to find the true dauphin than his mother … Marie Antionette.

There is no shortage of mystery, action, escape, suspense, heart, or fascination in the novels rapid paced but carefully drawn plot, and Bayard’s prose and turns of phrase are a delight to read:

Square and proud and blunt, built on geographical lines.

***

And here his fingers form a bud round his mouth and the name flowers forth, like a shower of pollen.

“Vidocq.â€

***

“If you have another lost king to peddle, Madame, you’ll have to knock on someone else’s door.â€

“I’m peddling nothing,†she answers, the first touch of frost crisping her voice. “It was Leblanc who believed, not I. And if he was wrong,” she says, rising and fronting him, “May I ask why he is dead?â€

She waits, with great courtesy, for his answer. Then tilting her head in deference, she asks: “Surely, there would be no need to kill a man who was laboring under a delusion.â€

It is a delightful book, a truly great read in the tradition of Zafon, Perez Reverte, Eco, Matthew Pearl, and yes, though there is no locked room or miracle crime, John Dickson Carr. It is simply a superb old-fashioned book book, a page turning, mind and heart engaging, first class read, and at its center, one of the most fascinating mysteries of all time, not what happened to the dauphin; but Eugene Francois Vidocq himself.

Mon 9 Jun 2014

NIGHT KEY. Universal Pictures, 1937. Boris Karloff, Warren Hull, Jean Rogers, Alan Baxter, Hobart Cavanaugh, Samuel Hinds, Ward Bond. Director: Lloyd Corrigan.

This film, as I understand it, was unavailable in the non-bootleg market for some time, but it finally made an official appearance in a nicely done Boris Karloff box set that came out about eight years ago. I think it safe to say that if Mr. Karloff were not in this film, this would be yet one more orphaned film never to see the light of day on DVD, much less one as clear and crisp as this one is.

Night Key, though, might disappoint those fans of Mr. Karloff who think of him as only a villain or a mad scientist (often both at the same time). He plays an elderly old inventor named Dave Mallory in this one, a bumbling old fellow who got cheated out of the royalties for his earlier invention, one that has made thousands if not millions for the owner of a security firm who has used his electronic locking device for several years now, installed in hundreds if not thousands of businesses, both large conglomerates and small mom-and-pop’s.

So much a bumbling old fellow that when he comes up with a new invention, one that improves on the old one by a huge factor, where does he go with it? To the very same guy who cheated him once before. Even using a lawyer to draw up the contract does not avail – the lawyer himself is crooked.

To avenge himself upon these miscreants, the near-sighted Dave Mallory recruits a fellow in small crime (Hobart Cavanaugh, as “Petty Louieâ€) to break into firms that use the old security device, not to steal or thieve, but to rummage around, rearrange things, and simply let the bad publicity take its toll.

There are two distinct parts to this movie, split right down the middle at the halfway point. The first is nearly a comedy-type adventure as well as it is a set-up for the second half – it turns out that Petty Louie was the lucky 10,000th victim nabbed in the act by the security company’s first device, only to be snatched out the lockup by Mallory and the skillful use of the new one – and Mr. Karloff’s version of an elderly old man shuffling around in a constant state of bewilderment is right on – body language and all. (He was 50 at the time. His character seems to be nearing his eighties.)

But the second half, which begins the minute a gang of real crooks gets wind of Mallory’s new device, is as straightforward as a line drawn from this point to the next. Lots of cars speeding their way down streets, sirens wailing; kidnapping and other threats at gun point, and subsequent shootouts – there’s not much funny stuff going on here, especially not when one the primary participants ends up dead, to the notice of very few. Mr. Karloff’s skill in creating the wonderful character which he did is all but wasted.

There is also a small romance going on throughout the film, between one of the security guards (Warren Hull, in a silly uniform throughout) and Jean Rogers (Dale Arden, once upon a time), which serves largely as a time-filler. It does make one wonder, though, how old bumbling scientists and inventors obsessed with their work ever find the time and opportunity be sire such beautiful daughters as they do in movies such as this one.

Mon 9 Jun 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

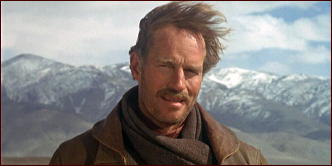

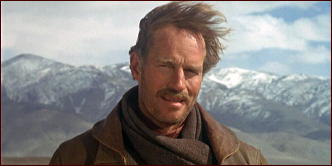

WILL PENNY. Paramount Pictures, 1968. Charlton Heston, Joan Hackett, Donald Pleasence, Lee Majors, Bruce Dern, Ben Johnson, Slim Pickens, Anthony Zerbe, Jon Gries. Screenwriter-director: Tom Gries.

Will Penny is a Western drama starring Charlton Heston as an aging cowhand caught between the only life he knows, that of a rugged, itinerant cowboy, and the love of a beautiful woman who wants to settle down with him. While the movie is neither a work of cinematic excellence, nor one of the best Westerns ever made, it is perhaps one of Heston’s finest, and least “epic,†big screen performances. Even if you’re not particularly a Heston fan, it’s worth watching.

The film may not resemble a traditional Western in terms of narrative or structure but contra Roger Ebert, Will Penny is very much part of the Western genre. That said, the film is best understood as a character study set in the Old West and as a filmmaker’s attempt to portray the life and psychology of a cowhand as realistically as possible.

While there are several notable flaws that do detract from the overall project, the film does succeed in providing the viewer with a glimpse of a West that was far less glamorous, and far more lonesome, than in the vast majority of shoot-them-up B-Westerns.

The plot really isn’t all that complicated. (If you haven’t seen the film yet, you might want to skip down a few paragraphs to avoid spoilers.) In fact, the plot’s simplicity is what makes what otherwise has the feel of made-for-television movie work as a film.

Will Penny (Heston) is an aging, illiterate cowhand working jobs when and where he can find them. After finishing one job, Will Penny and his two friends, Blue (Lee Majors in a rather undistinguished early film role) and Dutchie (a vastly under-utilized Anthony Zerbe) look for future work.

Along the way, they get into a confrontation with Preacher Quint, a bearded, wild-eyed, Bible quoting, madman (a somewhat miscast, overacting Donald Pleasence) and his family of misfits, over an elk. Penny shoots and kills one of Quinn’s sons with a rifle. The grieving and crazed father retreats, announcing to the world that he’ll seek to avenge his son’s killing.

During the gun battle, Dutchie ends up shooting himself in the chest. The three men then travel in search of a doctor, encountering Catherine Allen (a lovely, classy Joan Hackett) and her son, Horace, (portrayed by Jon Gries, son of writer/director, Tom Gries) in a tavern along the way.

After a series of not particularly compelling events, Quint and his remaining sons catch up with Will Penny, gravely injuring him. Allen nurses Will Penny back to health and, as might be expected, she begins to fall in love with him.

Will Penny, for his part, is both attracted to and confused by, the domestic lifestyle she and Horace take for granted. He develops a particular fondness for the young Horace, becoming a father figure to him.

Preacher Quint eventually returns – yet again – and wreaks havoc on the Allen household. In a final showdown, Will Penny, along with Blue and Dutchie who appear oddly out of nowhere at the most opportune time imaginable, take on the Quint family, eventually killing the lunatic patriarch.

Allen’s feelings toward Will Penny are now perfectly clear. Despite the fact that she has a husband out in Oregon, she wants him to marry her. Her plan is for them to settle down together as homesteaders. Will Penny is mighty tempted by the idea, but he just doesn’t see it as a viable option. After all, he’s nearly 50, an old man for that time and place. The only life he’s ever known is that of an itinerant cowhand; he simply couldn’t imagine giving it all up for a life of domesticity.

There is no happily ever after. Despite Allen’s entreaties, Will Penny decides to ride off with Blue and Dutchie, leaving Allen and Horace behind him.

When discussing Will Penny, “authenticity,†seems to be the key word. Will Penny is a character study of a lonesome, somewhat taciturn cowhand. He is not only illiterate, but he’s embarrassed by it. He prefers not to fight with his hands, as those are, in his estimation, hands are designed for working, not fighting. Instead, he makes use of a skillet in one fight and of his legs in others. The whiskey he drinks burns his throat. Most of all, Will Penny is extraordinarily, painfully, awkward around women.

But is the film, as writer/director Tom Gries intended, a realistic portrayal of a cowboy? I guess that depends. The Old West was a large place geographically and hosted a wide array of characters, good and bad, normal and strange, ebullient and bashful. Will Penny does, however, succeed in avoiding the obviously embellished features that mar other portrayals of cowboys, turning them into larger than life figures.

Heston’s Will Penny isn’t perfectly clean, well-spoken or comfortable in society. He also doesn’t like killing men much, either. He’s no romantic hero. He’s just a regular guy who comes to realize that the true villain in his life wasn’t Preacher Quint, but rather time and circumstance.

Will Penny may not be a great Western, but it’s a good one, a film that you’ll probably want to think about for a while before you form your own opinion on whether it works or not.

Sun 8 Jun 2014

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Last month I revisited a number of short novels — what the immortal Harry Stephen Keeler liked to call novellos, with the accent on the nov — but when I finished that column I felt like checking out a few more specimens and pulled down some volumes by Rex Stout, who at least among Americans was and still is the best known performer at that length.

Many decades ago I had read almost all the Nero Wolfe novels, long and short alike. In fact Wolfe’s last bow, A FAMILY AFFAIR (1975), was the first book I reviewed for the now long defunct St. Louis Globe-Democrat, and I still remember the book page editor adding a paragraph to tell readers that Stout had died, at age 88, between the time I’d sent in my review and the day it was published.

Rereading a couple of Wolfe’s shorter exploits recently, I enjoyed them as much as ever but found, as I’d noticed long ago, that Stout’s well-known habit of making up the plots as he went along often led him to paint himself into a corner. Take for example “Not Quite Dead Enough†(American Magazine, December 1942; collected in NOT QUITE DEAD ENOUGH, 1944).

This very early Wolfe novello takes place a few months after Pearl Harbor. Archie Goodwin, a newly minted major in Military Intelligence, is assigned to recruit his former boss, who would prefer to lose a pile of weight and join the infantry so he can kill Germans himself. Archie carries out his mission by framing himself for a murder and all but forcing Wolfe to clear him.

This time the sage of West 35th Street actually exposes the truth of the matter by something like deduction but, as he rightly points out at the wrap-up, the culprit’s scheme was “the silliest idea in the history of crime.†(Once Archie’s on-again-off-again girlfriend Lily Rowan tells the truth, as she’s bound to in due course, the only possible killer is the one who did the deed.)

In “The Twisted Scarf†(American Magazine, September 1950; collected in CURTAINS FOR THREE, 1950, as “Disguise for Murderâ€) the murder takes place in Wolfe’s own office on a day when he has allowed the members of the Manhattan Flower Club to invade the brownstone and admire his orchids.

The victim? A young woman who, shortly before her demise, took Archie aside and told him that while touring the plant rooms she had seen the person who had murdered a girlfriend of hers a few months earlier.

There’s much more physical action at the climax of this novello than one usually finds in Stout, and the murderer’s identity is a genuine surprise, but there wouldn’t have been a story at all except for the culprit having done something abominably stupid over which I shall draw a Salome’s veil except for those who opt to strip it off by clicking here.

I’m now going to change the subject. Well, not really.

Most mystery readers in my age bracket are likely to have read a few novels or stories by Frank Kane (1912-1968), the creator of PI Johnny Liddell. In his earliest appearances, which date back to around 1944, Liddell would probably have reminded most readers of Dashiell Hammett’s dumpy, overweight and streetwise protagonist The Continental Op.

One of those early tales was “Suicide†(Crack Detective Stories, January 1945), in which Liddell tries to prove that a man who apparently killed himself by eating his gun was actually murdered. This story wasn’t in either of Kane’s short story collections (JOHNNY LIDDELL’S MORGUE, 1956, and STACKED DECK, 1960) but was included in that now rare anthology RUE MORGUE NO. 1 (1946).

Who edited that anthology? Rex Stout and a guy named Louis Greenfield. How is that relevant here? Because the gimmick from “Suicide†pops up three years later in the Nero Wolfe novello “The Gun with Wings†(American Magazine, December 1949; collected in CURTAINS FOR THREE, 1950).

Didn’t I say I wasn’t really going to change the subject? It seems that when Stout didn’t make up his plots as he went along he took them where he found them.

Soon after Mickey Spillane and his sadistic sleuth Mike Hammer appeared on the scene and quickly transformed PI fiction — whether for better or worse is a matter of taste — Frank Kane decided to reconfigure Johnny Liddell into something of a Hammer clone, younger and better-looking and tougher and sexier than in his original incarnation, albeit without the carnage and psychotic rants that were the early Spillane’s trademarks.

The Liddell books do have their fans but for my money, if ever there were a truly generic PI series this is it. The writing is flat, the plots and characters from stock, the various adventures so interchangeable that Kane thought nothing of recycling whole passages from one Liddell novel into another. (Wasn’t it Marv Lachman who first discovered this?)

How fitting that late in the Fifties, when the first Mike Hammer TV series was launched, one of the first writers tapped to crank out scripts for it was Kane.

Ah yes, the first Mike Hammer TV series. I don’t believe I’ve ever written it up before so it just might make a nice subject for next month’s column. Don’t touch that dial!

Sun 8 Jun 2014

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

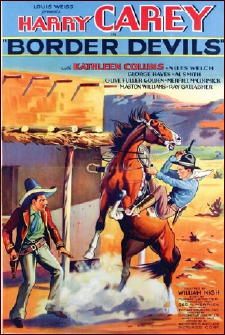

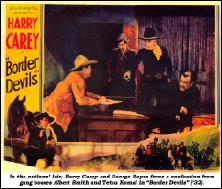

BORDER DEVILS. Supreme Pictures / Weiss Brothers Artclass Pictures, 1932. Harry Carey Sr., Kathleen Collins, George (later “Gabbyâ€) Hayes, Olive Carey and Tetsu Komai. Script and continuity by Harry P. Crist, based on a story by Murray Leinster. Directed by by William Nigh.

One of the first things you notice about Border Devils is that it’s based on a story by Murray Leinster, who gets a credit just under the title. And it would be interesting to know which one, because as the film unfolds we see some of the signature trademarks of Leinster‘s style all over it.

The story starts with Harry Carey Sr. and his partner (don’t worry about who played him; he’s only in one scene anyway) following up a lead on a mysterious oriental criminal mastermind of the west, known only as The General. They’re drugged, the partner murdered (see?) and Carey framed for it.

In due course, Carey becomes first a fugitive, then an investigator under a couple of assumed names, and finally he uncovers a plot to steal the heroine’s ranch. (How do they keep coming up with these new ideas?) He also picks up a more durable partner in the person of (who’da thunkit?) George “Gabby†Hayes.

Harry and Gabby spend the rest of the film running down The General, riding up the plains, and just generally playing cowboy as they try to sort out just who’s working for the Yellow Peril and who ain’t. In the course of things, the story keeps wavering between some grandiose plot of the General (seen only in shadows at first by his frightened minions) and the more mundane matter of the heroine’s ranch, until our doughty heroes manage to penetrate the sinister cabal and unmask the baddies once and for finally.

It’s easy to see the elements of Leinster’s style here: the massive conspiracy that figures in his sci-fi, the shifting identity of the hero, and the generally peripatetic nature of the tale as our cowboy commandos shuttle hither and yon like horsing lot attendants.

Unfortunately, it’s all a rather shoddy affair, one of a series of less-than-inspired films by producer Louis Weiss — who would later be responsible for The White Gorilla. His westerns with Harry Carey, done at a time when the once-great Western star obviously needed cash, are uniformly slow-paced, cheap and cheerless affairs, and this one is right at the bottom of the barrel.

Word has it that Carey actually had to sue Weiss for his salary, but it doesn’t show in his performance; the aging western star is as leathery-tough as ever, and a pleasure to watch, even in this seamy milieu.

So like I say, it’s just a shame to see him in this dreadful mess. Director William Nigh seems to have been not so much directing as sleep-walking, and as for the “script and continuity†— well, they’re perfunctory and non-existent, respectively. Characters come on the screen without introduction, say a few words in reference to some aspect of the plot, then get interrupted by some other characters who enter the scene for no apparent reason and everyone talks until the scene shifts to something else that seems to have little if any relation to whatever preceded it.

I remember thinking as I watched that whoever took credit for “script and continuity†ought to be ashamed of himself, and sure enough, he was: it turns out that the credited “Harry P. Crist†was actually a pseudonym for a sometimes-director named Harry Fraser.

If you’re not familiar with Fraser, let me just say that he worked in films from the Silent days to the late 1950s without ever once showing the fainted glimmer of interest in whatever he turned his hand to. Those who celebrate the late Ed Wood should bow their heads and positively worship Fraser, who, come to think of it actually worked on the Wood-scripted Bride and the Beast. Which should give you some indication of his talent. For the record, his last official credit as a feature film director was Chained for Life, a film so tasteless I must get around to reviewing it someday.

But getting back to Border Devils, I guess I should marvel at the talent of Leinster’s vision and Harry Carey’s charismatic presence. If they don’t exactly triumph over their surroundings, at least they shine through enough to be discernible.

Sat 7 Jun 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

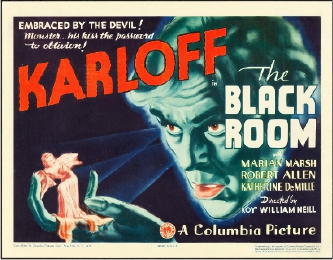

THE BLACK ROOM. Columbia Pictures, 1935. Boris Karloff, Marian Marsh, Robert Allen, Thurston Hall, Katherine DeMille. Director: Roy William Neill.

The Black Room, although not as well known as the classic Universal Studios horror films from the same era, is a taut, suspenseful, and visually crisp Gothic thriller starring Boris Karloff. In a memorable performance that demonstrates his strength as an actor, Karloff portrays two twin brothers, the evil, dissolute Gregor and the charmingly naïve Anton, the last remaining members of the de Berghmann family.

Directed by Roy William Neill (best known for directing some of the Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce Sherlock Holmes movies), the film makes skillful and economical use of decorative settings, shadowy lighting, unique camera angles, and repetitive music to convey a sense of impending doom and otherworldliness. As Joe Dante accurately notes, there is a fairy tale quality to The Black Room. The majority of film takes place in a castle, there’s horses and carriages a plenty, a prophecy fulfilled, and a beautiful maiden endangered by a madman and his demonic love for her.

The plot is fairly straightforward. We’re transported to a dreamlike land somewhere in central Europe. Twin brothers, Gregor and Anton, are born and their father, patriarch of the de Berghmann dynasty, isn’t happy about it. Not without good reason, for there’s a prophecy that holds that, when twin brothers are born in the family, the younger brother will end up killing the older one.

Specifically, it’s been written that younger brother kill commit fratricide in the black room, the castle’s oubliette. Although they are twins, we learn that Gregor is one hour older than his brother Anton, who was born with a paralyzed right arm. (How else would we tell them apart?) The stage is set for mystery and murder.

Fast forward twenty years. We learn that the disheveled Baron Gregor (Karloff) is a brute, a dissolute tyrant in a castle keeping busy by oppressing the peasants and violating their women. The townsfolk have had just about enough, but they aren’t quite sure how to get rid of the mad baron. Assassination attempts have been made on his life.

Enter twin brother, dapper and naïve Anton, also portrayed by Karloff, who returns to his hometown after traveling in Europe. The two brothers reunite. After killing Mashka (Katherine DeMille) who witnessed his criminal acts, evil brother Gregor abdicates and turns power over to Anton, but not for long. Gregor lures Anton into the eponymous black room, pushes him down into a pit where he dies, a knife resting between his body and his right arm.

This is when Karloff’s skill as an actor really shines through. Now, he’s portraying a third character, as it were: evil Gregor pretending to be Anton. The murdering nobleman has his sights set on the beautiful, white-clad Thea (Marian Marsh, often bathed in a soft white light), niece of Colonel Hassell (Thurston Hall).

But she’s not in love with the baron. Her heart belongs to the upstanding Lt. Lussan (Robert Allen) who ends up being convicted for the murder of Col. Hassell, a murder that Gregor-as-Anton commits when the colonel unmasks his true identity. If it sounds somewhat complicated, trust me when I say it’s really not.

Karloff is a skilled enough actor to pull off these three distinct roles. Roy William Neill’s direction gives the viewer enough time and visual cues to easily follow what’s happening every step along the way, including in the final showdown where the prophecy is indeed fulfilled after a dog forces Gregor-as-Anton to use his right arm, demonstrating to everyone that he’s an imposter.

The Black Room has some particularly notable camera work, which makes the film significantly better than many other horror films from the same era. Most of the time, the viewer is not on the same eye level as are the characters. Often times, the actors are shot from angles either significantly beneath them, even at foot level, or above them. This gives the impression that we are meant to be conscious of our role as spectators, peering through the looking glass into a fantastic realm. Look, also, for the scene in which the camera looks up at Anton right before his brother pushes him down into the pit.

The film, perhaps not surprising in a movie about twin brothers, also makes ample use of mirrors and reflections. For instance, the first we see of Gregor immediately after he murders Mashka is as a reflection a mirror, shot at an angle. There’s also a great soliloquy in which Gregor-as-Anton talks to himself in a mirror and an eerie scene in which Gregor talks to himself in a reflection in the black room.

The film repeatedly juxtaposes faith with superstition. There are numerous scenes with crosses and crucifixes, both in and out of a graveyard. Likewise, there are two important scenes in which Thea and Lt. Lussan have intense discussions in front of Virgin Mary statues. As far as superstition, there is not only the matter of the prophecy, but also a black cat – one real and one made of wood – that shows up in the film. It’s worth looking out for.

In conclusion, The Black Room is one of those forgotten gems of 1930s cinema. It may not be a classic, but in many ways it’s as good as many of the best known Universal films from the same era and far better than the Universal B-films from the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Karloff is on the top of his game here. There’s one scene in which he as Gregor is holding a knife and talking to himself as he carves a pear, demonstrating just how crazed and inattentive he is. That’s the type of acting that makes the film really worth watching. The story, while not the most creative, is not bad either.

« Previous Page — Next Page »