June 2014

Monthly Archive

Fri 6 Jun 2014

RAYMOND CHANDLER’S FAVOURITE CRIME WRITERS AND CRIME NOVELS – A List by Josef Hoffmann.

In his letters and essays Chandler frequently made sharp comments about his colleagues and their literary output. He disliked and sharply criticized such famous crime writers like Eric Ambler, Nicholas Blake, W. R. Burnett, James M. Cain, John Dickson Carr, James Hadley Chase, Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle, Ngaio Marsh, Dorothy L. Sayers, Mickey Spillane, Rex Stout, S. S. Van Dine, Edgar Wallace. A lot of Chandler’s criticism was negative, but he also esteemed some writers and books. So let’s see, which these are.

A problem is that he sometimes had a mixed or even inconsistent opinion. When the positive aspects predominate the negative ones I have taken the writer or book on my list.

The list follows the alphabetical order of the names of the mystery writers. Each name is combined with (only) one source (letter, essay) for Chandler’s statement. I refer to the following books: Selected Letters of Raymond Chandler, edited by Frank MacShane, Columbia University Press 1981 (SL); Raymond Chandler Speaking, edited by Dorothy Gardiner & Kathrine Sorley Walker, University of California Press 1997 (RCS); The Raymond Chandler Papers: Selected Letters and Non-Fiction 1909 – 1959, edited by Tom Hiney & Frank MacShane, Penguin 2001 (RCP); “The Simple Art of Murder,” in: The Art of the Mystery Story, edited by Howard Haycraft, Carroll & Graf 1992.

I am rather sure that the list is not complete: It does not include all available sources nor all possible writers and books.

THE LIST:

Adams, Cleve, letter to Erle Stanley Gardner, Jan. 29, 1946 (SL)

Anderson, Edward: Thieves Like Us, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Sep. 27, 1954 (SL)

Armstrong, Charlotte: Mischief, letter to Frederic Dannay, Jul. 10, 1951 (SL)

Balchin, Nigel: The Small Back Room, letter to James Sandoe, Aug. 18, 1945 (SL)

Buchan, John: The 39 Steps, letter to James Sandoe, Dec. 28, 1949 (RCS)

Cheyney, Peter: Dark Duet, letter to James Sandoe, Oct. 14, 1949 (RCS)

Coxe, George Harmon, letter to George Harmon Coxe, Dec. 19, 1939 (SL)

Crofts, Freeman Wills, letter to Alex Barris, Apr. 16, 1949 (RCS)

Davis, Norbert, letter to Erle Stanley Gardner, Jan. 29, 1946 (SL)

Faulkner, William: Intruder in the Dust, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Nov. 11, 1949 (SL)

Fearing, Kenneth: The Big Clock, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Mar. 12, 1949 (SL); The Dagger of the Mind, The Simple Art of Murder

Fleming, Ian, letter to Ian Fleming, Apr. 11, 1956 (SL)

Freeman, R. Austin: Mr. Pottermack’s Oversight; The Stoneware Monkey; Pontifex, Son and Thorndyke, letter to James Keddie, Sep. 29, 1950 (SL)

Gardner, Erle Stanley, letter to Erle Stanley Gardner, Jan. 29, 1946 (but not as A. A. Fair, letter to George Harmon Coxe, Dec. 19, 1939) (SL)

Gault, William, letter to William Gault, Apr. 1955 (SL)

Hammett, Dashiell, The Simple Art of Murder

Henderson, Donald: Mr. Bowling Buys a Newspaper, letter to fredeeric Dannay, Jul. 10, 1951 (SL)

Holding , Elisabeth Sanxay: Net of Cobwebs, The Innocent Mrs. Duff, The Blank Wall, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Oct. 13, 1950 (RCS)

Hughes, Dorothy, letter to Alex Barris, Apr. 16, 1949 (RCS)

Irish, William (Cornell Woolrich): Phantom Lady, letter to Blanche Knopf, Oct. 22, 1942 (SL)

Krasner , William: Walk the Dark Streets, letter to Frederic Dannay, Jul. 10, 1951 (SL)

Macdonald, Philip, letter to Alex Barris, Apr. 16, 1949 (RCS)

Macdonald, John Ross: The Moving Target, letter to James Sandoe, Apr. 14, 1949 (SL)

Maugham, Somerset: Ashenden, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Dec. 4, 1949 (SL)

Millar, Margaret: Wall of Eyes, letter to Alex Barris, Apr. 16, 1949 (RCS)

Nebel, Frederick, letter to George Harmon Coxe, Dec. 19, 1939 (SL)

O’Farrell, William: Thin Edge of Violence, letter to James Sandoe, Aug. 15, 1949 (SL)

Postgate, Raymond: Verdict of Twelve, The Simple Art of Murder

Ross, James: They don’t dance much, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Sep. 27, 1954 (SL)

Sale, Richard: Lazarus No. 7, The Simple Art of Murder

Smith, Shelley: The Woman in the Sea, letter to James Sandoe, Sep. 23, 1948 (SL)

Symons, Julian: The 31st of February, letter to Frederic Dannay, Jul. 10, 1951 (SL)

Tey, Josephine: The Franchise Affair, letter to James Sandoe, Oct. 17, 1948 (RCS)

Waugh, Hillary: Last Seen Wearing, letter to Luther Nichols, Sep. 1958 (SL)

Whitfield, Raoul: letter to George Harmon Coxe, Dec. 19, 1939 (SL)

Wilde, Percival: Inquest, The Simple Art of Murder.

Fri 6 Jun 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

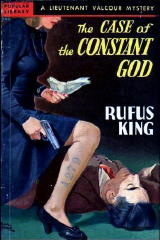

RUFUS KING – The Case of the Constant God. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1936. Popular Library #193, no date [1949].

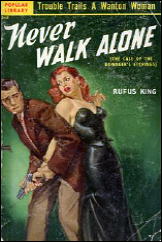

— The Case of the Dowager’s Etchings. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1944. Popular Library #362, 1951, as Never Walk Alone.

Not only is Sigurd Repellen a nasty blackmailer in The Case of the Constant God, he is allergic to shrimp, both of which drawbacks cause a young lady to commit suicide. When Repellen presumably is accidentally killed by the young lady’s husband, the other family members who witness the death try to cover it up.

They might have succeeded, but the blow on the head that caused Repellen’s seeming heart attack and death turns out, upon medical examination, to be a blow upon the head and a .22 bullet in the heart.

The family’s transporting the dead man around New York doesn’t help any. This odd behavior comes to the attention of Lieutenant Valcour, who joins the group on a yacht too late to prevent another murder, though in time to capture the killer.

Not quite fair play, but moderately amusing. And could someone tell me why King kept putting Valcour aboard yachts? For a New York City police detective, he spent a lot of time on the water.

Feeling guilty about not helping in the war effort, Mrs. Chatterton Giles, who is the dowager in The Case of the Dowager’s Etchings and who is in her seventies, decides to rent rooms to defense-plant workers. The four rooms are taken quickly, by two men Mrs. Giles likes — well, one of them had bought her etching at an art show — one man who looks uncomfortably like Humphrey Bogart, and a young woman obviously no better than she should be.

The night that several of the roomers move in, there is murder on the grounds of the Giles estate. What’s even worse, Mrs. Giles’s war-hero grandson appears to have been involved.

Mrs. Giles is an interesting character, but the plot is lightweight. Not one of King’s better efforts.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

Thu 5 Jun 2014

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

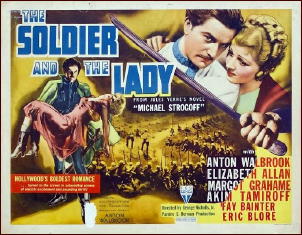

THE SOLDIER AND THE LADY. RKO Radio Pictures, 1937. Anton Walbrook (debut), Elizabeth Allen, Akim Tamiroff, Margot Grahame, Fay Bainter (debut), Eric Blore, Edward Brophy, Paul Guilfoyle, Paul Harvey. Screenplay by Mortimer Offner, Anthony Veiller, Anne Morrison Chapin, based on Michael Strogoff Courier of the Tzar by Jules Verne. Directed by George Nichols Jr. as George Nicholls Jr.

This remains one of the most faithful and well done of all Jules Verne’s books adapted to film, an epic portrayal of Verne’s novel about a heroic courier for Alexander II who brings down the Moslem Tartar rebellion of 1870 and saves Russia while finding love and facing one daunting task after another.

Though Strogoff is another of Verne’s naturalist romantic heroes in the line of Ned Land from 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Nik Dek from Castle Carpathian, he has also been rightfully called a 19th century James Bond.

The splendid cast is the first great asset of this film. Anton Walbrook made his American film debut as Strogoff, and proves a fine swashbuckler more adept than most at the dramatic scenes (or melodramatic in this case). It isn’t as subtle as many of his fine later films, but then it isn’t supposed to be, and he more than suggests the characters nobility and courage.

Elizabeth Allen (wife of Robert Montgomery and mother of Elizabeth) is the heroine Nadia, beautiful, aristocratic and innocent; Margot Grahame the femme fatale Zangarra with a heart that can be melted by a noble hero; and Fay Bainter in her strong film debut is Michael’s mother. Eric Blore and Edward Brophy are English and American war correspondents for comedy relief, and Paul Harvey the Tzar.

But the film is stolen to a great extent by Akim Tamiroff as the perfectly named Ivan Ogareff, the traitorous, brutal, sly, cunning, and sadistic Tartar agent plotting to use the uprising to grab power and wealth. It’s Tamiroff at his scenery chewing best as a thorough going rotter, and audiences must have cheered when he meets his deserved end.

The Tzar himself dispatches Strogoff as a courier to his brother in Irkutsk with instructions that will save him and the city from the Tartar’s treachery, adding for Michael not to even acknowledge his mother, Fay Bainter, whom he will see on his journey to the place of his birth.

Things go bad quickly: the lovely Nadia is captured when the Tartar’s assault a barge she and Strogoff travel on looking for the courier they know the Tzar sent, and he is left for dead in the river. He escapes but is now afoot, and the Tartars are closing in. Finally he too is captured and Ogareff’s mistress Zangarra, Margot Grahame, who saw him in Moscow is to identify the courier, but she lies and Ogareff must threaten to torture the courier’s mother to bring Strogoff out.

He comes forth of course, and confesses he destroyed the papers, and in one of the most brutal scenes in Verne’s works Ogareff blinds him with a torch, a crime so brutal that Strogoff’s mother’s heart fails at the horror. It’s pretty strong stuff here too, and unlike almost anything else in Verne’s fiction.

Now Ogareff poses as the Tzar’s courier to deceive the Tzar’s brother, and Strogoff and Nadia struggle to reach Irkutsk in time.

Ogareff hasn’t calculated on one thing — Strogoff isn’t blind — the tears he wept saying goodbye to his mother kept the flames from burning his eyes. He slays Ogareff, the city is saved, the rebellion put down with its leader dead, and Stogoff is given a medal by the Tzar and promoted to Colonel as the Tzar praises his heroic mother’s sacrifice.

Walbrook had starred in the 1936 French version of the story so RKO wisely chose him in the role so they could use the sweeping scenes of battle and marching armies filmed for it. It proved a wise choice and the film was a major hit. Granted it might have been better from one of the bigger studios like Warners or MGM with a director better suited to epics, but it is still a fine swashbuckler very close to Verne’s novel.

This was remade in the 1960‘s in Germany with Curt Jurgens as Strogoff (known both as Michael Strogoff and Soldier and a Lady) in color, and not a bad film itself, though difficult to find.

But it’s this version that is the standout, a handsome adaptation of the classic novel with a fine cast and many sweeping scenes from the French original. From the look of things it is clear the French version beats them both, but as far as I know it is lost, so like the scenes of the silent Gold included in The Magnetic Monster, this is all we have.

Mon 2 Jun 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

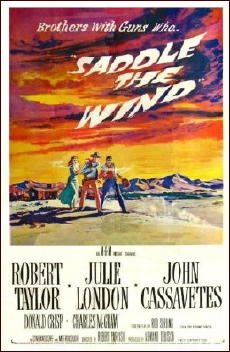

SADDLE THE WIND. MGM, 1958. Robert Taylor, Julie London, John Cassavetes, Donald Crisp, Charles McGraw, Royal Dano. Screenplay: Rod Serling, based on a story by Thomas Thompson. Music by Elmer Bernstein. Directors: Robert Parrish & John Sturges, the latter uncredited, according to IMDb.

Saddle The Wind is a Western set on the frontier in the post-Civil War era. Veteran actor Robert Taylor and a youthful John Cassevetes, the latter in one of his earliest film roles, portray brothers Steve and Tony Sinclair, respectively. The two men are irreparably divided over the necessity and propriety of violence. Joining them on their journey into fatal conflict is singer/actress Julie London who portrays Tony Sinclair’s mysterious love interest, Joan Blake.

The film is as much a Greek tragedy set in the American West as it is a traditional Western. The themes of personal fate, hubris, and historical inevitability all feature strongly in both the film’s text and subtext.

The philosophical question of whether a man is born bad or goes bad because of his environment — the age-old question of nature versus nurture — is both explicitly and implicitly touched upon throughout the film. Saddle The Wind also explores the effects and ramifications of violence on men and women, and societies more generally.

The film begins with a depiction of frontier aggression and violence. Larry Venables (a mean-looking Charles McGraw) enters a tavern, demands service, and aggressively queries for the whereabouts of Confederate veteran Steve Sinclair (Taylor). But it’s not Steve with whom Venables ends up doing battle. Rather, it is younger brother Tony, whom Steve always believed had something wrong with him when it came to violence, who engages in a standoff with Venables.

Tony shoots and kills Venable, setting off a chain of events that spin out of his control. The sick thrill of murdering a man, even if it were justified, goes to Tony’s head. With liquor, his wildness only increases. Soon Tony and a friend are out making trouble for what they perceive to be gathering of local squatters. Leading the group is Clay Ellison (Royal Dano), a Union veteran from Pennsylvania who has a deed to the land.

It’s not long until Tony Sinclair is angry at — and violent toward — almost anyone who crosses his path, including the local patriarch and landowner, Dennis Dineen (Donald Crisp). This turns out to be a big mistake, and it ends up with older brother Steve having to put an end to his younger brother’s reign of terror. The film culminates in a final, violent showdown between the Brothers Sinclair. The camera work, particularly the angles at which the actors are captured on film, and the music leading up to this crucial event are memorable.

Without giving away the ending, let’s just say that you may slightly caught off guard. (I watched it a second time just to make sure I understood it correctly.) I wasn’t expecting the film’s main conflict to resolve itself in the manner that it did, but if one does consider it to be a Greek tragedy set in the West, rather than a Western, it all makes perfect sense.

The film’s biggest flaw, ironically, may have been in casting Julie London for the role of Joan Blake. While London is certainly captivating and her singing of the movie’s eponymous title song has its saccharine charm, her character just comes across as somewhat inauthentic.

It’s hinted that she’s running from a violent past. Nevertheless, would a woman of her looks and her presumed social status really have joined up so quickly with an obvious immature hothead like Tony Sinclair after knowing him for less than a week? It strains credulity.

In many ways, Joan Blake is extraneous to the overall taut plot; the conflict between the sober, elder brother Steve and the reckless, younger brother Tony would have likely come to a head even without her presence in their midst. By not further developing the sole significant female character in the film, Serling weakened his overall solid script and made London’s contributions to Saddle The Wind less impressive than they could have been.

Although Saddle The Wind is unquestionably a Western, there is something very noir about the film, with Cassavetes’s character increasingly spiraling into a hellish realm of senseless violence, all of which culminates in his inevitable doom. None of the characters are remotely happy, at least not for very long.

The closest we see to true happiness is at the beginning of the film, when Tony Sinclair returns home and is reunited with his brother. From then on, no one really is remotely cheerful, at least not in any normal sense.

All the characters seem more resigned to their places in the world than particularly happy with them. Violence, death, loneliness, and struggle rule the land. It’s a bleak land, and one does one’s best to make the most of a less than optimal situation. Perhaps this was Rod Serling’s view of the American West?

In conclusion, Saddle The Wind is a unique film, somewhat distinct from the typical Western narratives of the era. In many ways, it’s a film about a loser rather than one about a hero. But it’s very much worth watching. With solid acting, great scenery, and a beautiful soundtrack composed by Elmer Bernstein, it’s a film that you won’t soon forget, particularly if you really consider what’s really going on with all the characters under their tough Western exteriors.

« Previous Page