July 2014

Monthly Archive

Sun 20 Jul 2014

THE ARMCHAIR REVIEWER

Allen J. Hubin

GEOFFREY MARSH – The Fangs of the Hooded Demon. Tor, hardcover, 1988; reprint paperback, 1989.

I’ve not before encountered Geoffrey Marsh and his Lincoln Blackthorne series, of which the present The Fangs of the Hooded Demon is the fourth. Blackthorne is a tailor in New Jersey, of all things, to whom incredible experiences accrue.

If Demon is any guide, these tales are part mystery and crime, part unresolved fantasy and mysticism, with Blackthorne functioning more or less in the role of private investigator. Or maybe a land-bound Travis McGee.

Here he’s hired, or maybe forced, to track down the titular fangs, which are bejeweled false teeth with reputed powers of rejuvenation if the right ritual is used at the right time. Various aged and villainous Hollywood rejects want the fangs desperately, and the peril-around-every-corner chase leads to New York, then to Oklahoma, and finally to the oozing swamps of Georgia.

Frantic and imaginative, and I suspect quite enjoyable if your tastes run to this sort of thing.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 11, No. 3, Summer 1989.

Bibliographic Note: It is now known that Geoffrey Marsh was one of several pen names used by Charles L. Grant (1942 – 2006), a noted horror and fantasy writer whose books sometimes verged into crime fiction territory, as did the Blackthorne novels.

The Lincoln Blackthorne series (as by Geoffrey Marsh) —

1. The King of Satan’s Eyes (1984)

2. The Tail of the Arabian, Knight (1986)

3. The Patch of the Odin Soldier (1987)

4. The Fangs of the Hooded Demon (1988)

Sun 20 Jul 2014

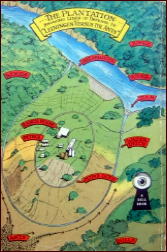

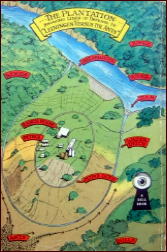

THE NAKED JUNGLE. Paramount Pictures, 1954. Eleanor Parker, Charlton Heston, Abraham Sofaer, William Conrad. Based on the story “Leiningen versus the Ants,” by Carl Stephenson (Esquire, December 1938); first published in Germany in 1937 as “Leiningens Kampf mit den Ameisen.” Director: Byron Haskin.

Fans and collectors of Old Time Radio shows will recognize the story this film is based on immediately. “Leiningen versus the Ants” must be among everyone’s all time Top Ten list of favorite episodes. It was produced at least four different times, on Escape 14 Jan 1948, 23 May 1948, 4 Aug 1949, and on Suspense, 29 Nov 1959. You can hear an MP3 version of the first of these here.

The radio version follows the story itself quite faithfully, that of a stubborn bull-headed plantation owner in South America who refuses to move away from his land in the face of a swarm of deadly ants two miles wide and ten miles long. The only difference is that in the radio version the District Commissioner returns to Leiningen’s compound to see whether (and how) he can make good on his promise to prevail against the deadly horde. He also helps provide half of the necessary narration.

The story can be read in twenty minutes, and it takes thirty minutes to listen to the radio show. How then is the running time of the movie some 95 minutes long? Easy. Add a preamble about an hour long, one introducing a mail-order bride to the tale, a lady from New Orleans previously unseen by Leiningen.

Charlton Heston is of course the obvious choice to play Leiningen, a fellow as stubborn and ignorant of the ways of women as he was later on in his portrayal of Captain Colt Saunders in Three Violent People (1956), which I reviewed here not too long ago.

Of course it could only happen in the movies that the mail-order bride would be as lovely as Eleanor Parker, but leave it to Charlton Heston’s character to reject her almost immediately, once he learns that she has been married once before. (He prides himself on having only new items in his house, including a piano, which of course the new Mrs. Leiningen is able to play, and quite well)

All in all, it’s sort of dull romance, and you just know that once the danger is over, the two of them will find a way to sort things out between them, if not before. In my opinion, as long as you’re asking me, the time the romantic problems take up could have been shortened considerably, thus giving us more time with the ants. (Some of us, who know full well what is coming in advance, may even be squirming in our seats in anticipation.)

The special effects are quite good, I hasten to add, and well worth the price of admission. So good, in fact, that I recognized some of the footage as being used again in an episode of the TV series MacGyver, “Trumbo’s World” (Season 1, Episode 6; 10 November 1985).

And oh yes, one other thing. William Conrad, who played Leiningen in the radio show that I hope you took (or will take) the time to listen to, played the role of the District Commissioner in The Naked Jungle.

Overall verdict: Medium well but no more.

Sat 19 Jul 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

BORDER INCIDENT. MGM, 1949. Ricardo Montalban, George Murphy, Howard Da Silva, James Mitchell, Arnold Moss, Charles McGraw. Director: Anthony Mann.

Border Incident is a film noir/crime film directed by Anthony Mann. It stars Ricardo Montalban as Pablo Rodriquez, a Mexican federal policeman, and George Murphy as Jack Bearnes, an American immigration agent. Set on the California-Mexico border, the movie follows the two government agents’ collaborative efforts to investigate the murder, and robbery, of Mexican farmworkers.

Unlike many movies categorized as films noir, there are no femme fatales, snappy bits of dialogue, or urbane gangsters in suits and fedoras.

There are, however, numerous moments of claustrophobic disorientation, including one stunningly effective sequence filmed on a water tower. There’s also a seedy neon-lit bar glimmering in the desert night and the harrowing murder scene of a helpless man. In Border Incident, nature is as noir as the city, with a desert canyon and quicksand proving that they can be just as deadly as a dame with a gun.

The film begins in a semi-documentary style, leading the viewer to believe he is about to watch a standard crime drama in which the good guys defeat the bad guys, everyone will slap each other on the back, and go out for drinks. When we first meet Pablo Rodriquez (Montalban) and Bearnes (Murphy), they are both clean, well dressed, and in good spirits.

It soon becomes apparent, however, that they’re not about to face anything typical. From the moment that Rodriquez goes undercover and befriends Juan Garcia (James Mitchell), a Mexican farm worker who wants to cross illegally, we get the sense that things aren’t going to go smoothly after all.

Anthony Mann sets the mood perfectly. The Mexican side of the border is chaotic, disorienting, and filled with sketchy characters that come out at night. Among them are the Teutonic-looking Hugo Wolfgang Ulrich (Sig Ruman), the proprietor of a lowlife bar, and his two thugs, Cuchillo (Alfonso Bedoya) and Zipilote (Arnold Moss). Although we never learn what a gruff German bar owner is doing in a border town, we do soon learn that he’s knee-deep in crime and is willing to utilize brute force against his perceived enemies.

As it turns out, Hugo is working with with an American farm owner on the other side of the border, a creepy looking guy by the name of Owen Parkson (Howard Da Silva) who treats his land like a plantation, and his workers like pawns on a chessboard. Parkson, along with his chief henchman, Jeff Amboy (Charles McGraw), are true villains. There’s nothing remotely amusing, let alone redeemable, about these two guys. Da Silva and McGraw may not have had star billing, but they are very effective in portraying criminals indifferent to human life and suffering.

Rodriquez and Bearnes succeed in infiltrating Parkson’s estate, but nothing goes according to plan. Both men face dangers that seem to come out of nowhere, or at least take them by surprise. It’s as if both men never expected to face such adversity in their current assignment. There are some very tense moments, almost all of which take place at night.

Border Incident isn’t a particularly well-known film noir, but it’s a very good one. The film successfully encapsulates many aspects of the noir genre, from the focus on the dark side of human nature to Mann’s skillful use of shadow and lighting to convey meaning. It’s a dark film, both metaphorically, and in its cinematography. Although it wasn’t a box office success, it is nevertheless a good example of what a talented director can do on a meager budget. Highly recommended.

Fri 18 Jul 2014

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

— The Thriller Library #538: Rough House: A Norman Conquest Story, by Berkeley Gray. 27 May 1939.

— Dixon Hawke Library #549: The Purple Doom of Doctor Krantz, [Anonymous]. 14 December 1940.

— The Sexton Blake Library S3 234: The Green Caravan, by Rex Hardinge. February 1951.

The British pulps came out of a similar tradition as those in America, and like the American brand walked a schizophrenic tightrope between adult and juvenile fiction. Sexton Blake, Nelson Lee, Dixon Hawke, all came from the boys’ papers popular at the turn of the century and well beyond.

Edgar Wallace, Leslie Charteris, John Creasey, Berkeley Gray all came from a slightly more sophisticated branch, though Creasey and Gray (Edwy Sealey Brooks) both wrote adventures of Sexton Blake.

Brooks wrote well over six million words of Blake material, creating Waldo the Wonder Man, who threatened to overwhelm Blake in his own book, before he was forced out because of age, at which point he created Norman Conquest and Inspector Ironside and became even more popular, writing well into the nineteen sixties, at least one Conquest adventure completed by his wife and son.

The British pulp The Thriller, edited by Monty Haydon, who discovered Charteris and Creasey, featured not only the more adult writers, but serials from the American pulp The Shadow, Sax Rohmer, and the dean of the British pulp creations Sexton Blake. Peter Cheyney came out of The Thriller, and a long list of familiar names with him, some of who saw their careers fade and returned in the 1950‘s to penning Sexton Blake adventures like Rex Hardinge and Hugh Clevely (Maxwell Archer, who got one film outing, and the Gang Smasher, who was unique because his assistant was a Jewish pawnshop owner).

It seems as if you can’t elude Sexton Blake in fiction or fact.

All of these short tales run some sixty or so pages, coming in around thirty five thousand words. All appeared in inexpensive paper editions, either in The Thriller, or digest size paperbacks.

They are reviewed in order of publication from the 1930‘s to the 1950‘s.

Norman Conquest, 1066, the Gay Desperado (before the word Gay was made impossible to use in any but a sexual sense) at one time ran with a fast crowd, the Saint, Blackshirt, the Toff, and the Baron, and in the United Kingdom he ran very close though he never quite made it to American shores.

In The Durable Desperadoes William Butler Vivian wrote fondly of Conquest, and I have to agree. His adventures have energy, speed, violence, a hint of sex in perpetual virtual live in girlfriend Joy ‘Pixie’ Everard (think Simon Templar’s Patricia Holm but Norman eventually marries his).

Gangsters, mad scientists, master criminals, spies, fifth columnists, just about all fell to Conquest’s outlaw ways. He even made it to the screen in the person of Tom Conway for one late but half decent film outing.

In Rough House Conquest is at his toughest, in a Saintly mode with more than a hint of Bulldog Drummond at the edges.

“Conquest? Did you say Conquest? Norman Conquest? Good heavens, I wonder if he’s the impudent rascal I believe he is? What would a man of his stamp would want in this house?â€

What Conquest wants is to warn Lord Chalston that a criminal in a rubber mask one Toowoomobo Dick wants Lord Chalston dead, and Conquest suspects it’s because Toowoomobo Dick under that rubber mask is:

“See my friend, I am the true Lord Chalston,†said Dick deliberately. “An aristocratic English peer with the face and skin of a black savage!â€

To be fair to Gray, he does at least make a case that Dick might have some reason to feel cheated out of what is rightfully his just because his mother had a distant grandfather with black skin and it showed up on her baby, but that doesn’t excuse murder or the wax effigies he makes of his victims. Dick is more than a little insane.

Racial stereotypes hung on in British popular fiction much longer and were much more of an issue than in American popular fiction, largely because the English were much less homogenous than their American cousins and foreign much more noticeable. Being a class based society didn’t help. As late as the 1950‘s a character in a Sexton Blake adventure (The Voyage of Fear by Rex Hardinge) is an Italian described as “touched by a tar brush.â€

Norman naturally goes a little ballistic when Joy/Pixie is kidnapped right under his nose and as usual charges right in, with less than spectacular results. In fact Joy has to rescue him:

Drawn as if by irresistible magnetism she turned again to the effigy of Norman. She could not keep her eyes off of it. She went closer, fighting an urge to turn on her heels and run. It was something about the figures eyes — she caught her breath painfully. These eyes were not glass. They were not the dead eyes of a waxwork. They were alive. They looked at her with intelligence and urgency.

“Norman,†cried Joy chokingly.

Even Norvell Page never entombed Richard Wentworth in wax. Of course she saves Norman, and he does for Lord Chalston in his own inimitable 1066 (get it, the Norman conquest) Gay Desperado way no doubt putting yet another gray hair in the head of Sweet William, his long suffering friend and adversary at Scotland Yard.

World War II posed a problem for rogues and gentleman adventurers. It wasn’t all that glamorous flitting about England in the blitz. Peter Cheyney managed all right with Slim Callaghan and Ettienne McGregor and turned to his best work in spy novels, but the Saint had to sail for the states to fight saboteurs (can you imagine the Saint in uniform?).

The Toff served in intelligence but all his adventures were home based affairs battling things like black marketeers, Norman Conquest fought Nazis at home when not ignoring the war completely, and the Baron was a sergeant manning a telephone for the RAF in a note typical for that grounded series. But Sexton Blake was in it tooth and nail, and where Blake went Dixon Hawke was sure to follow.

The most important thing to note about Dixon Hawke is that young Kenneth Millar, Ross Macdonald, was a fan, and the Hawke books are fun, but they are much closer to the comics than even the hero pulps.

The Purple Doom of Doctor Krantz has Hawke penetrating the Nazi high command as said Doctor Krantz. The opening sets the tone.

“Donner and blitzen,†he cursed. What a night and what a country. Only the pig dog British would build a prison in such a place.

By which remark Herr Gustav Stonberg revealed his utter lack of a sense of humour, for, as one of the leading members of the German Secret Police, the dreaded Gestapo, he had been responsible for building some of the worst concentration camps in Germany.

At least you know where you are. This is wartime England and subtle was not needed in the pulps. Never fear though, Dixon Hawke outwits Himmler himself, makes a daring escape with his friend Clavering, and gets shot down in a German plane by the RAF before he is rescued with the goods. “Good old Dixon Hawke …†as his boy pal Tommy (since Sexton Blake’s Tinker every hero needed a youthful assistant) says.

The Purple Doom of Doctor Krantz reads the way a good B wartime programmer plays, it even resembles the Raoul Walsh Errol Flynn flag waver Desperate Journey a bit with a touch of John Buchan’s Greenmantle thrown in (the bit where Hannay is in WWI Germany in disguise), as well as Manning Coles’ Tommy Hambledon in A Toast to Tomorrow and Drink To Yesterday. It’s closer to a Big Little Book or a juvenile than the pulps, but it is still fun, if not for the same reasons as slightly more mature fare.

Who doesn’t like to figuratively flip the bird to Hitler and Himmler?

The Green Caravan by Rex Hardinge is a Sexton Blake post-war adventure, and it is not for little boys. Philip Neal wants to marry beautiful English rose Mary Young, but the tormented Neal, who had a bad war in a ‘Nazi horror camp,’ was drawn to the gypsy woman Belle Hampton, she of the bulging bosom and flashing eyes, for darker needs. Now he can’t get rid of her, and the best solution seems to be murder.

The perfect murder! He realised that many men have tried to achieve it. Many have paid for their failure the full penalty demanded by the law. But what of those who succeeded? Nobody knows how many of them there have been. And if others succeeded why shouldn’t he?

Not the sanest of people this Philip Neal, and the bodies start falling like flies, random victims killed by three bullets from three guns without warning. Mary Young is scared and turns to Neal’s rival Ben Rorke. Ben survives a trap, and now Neal must be rid of him before he figures out who the killer is. So why not blow up the entire end of the hospital Ben is in?

…pack the dynamite — light it with a short fuse — then with the crossbow, from some convenient spot, fling the arrow with the dynamite into the room where Ben lay.

He misses Ben again, but suspecting the second attack on Ben was not coincidence Sexton Blake, called in on the case with Inspector Coutts of the Yard, has the word spread that Ben is dead and moves him to London. Blake is convinced the murders are not the work of ‘what the Americans call a psycho.†He sees a ‘deliberate plan†behind the crimes.

Ben leads to Mary who leads to Belle with whom she had a violent confrontation, which leads to Philip Neal who has the means and the brains to rig the clever traps the killer uses, but there has to be a motive. Even with evidence and motive they couldn’t charge Neal or convince a jury (unusual for the detective to bother with details like juries in any mystery), and the obvious victim, Belle Hampton, is as yet untouched.

If you don’t smell a trap coming, you haven’t been paying attention reading these and watching television and movies all these years.

“He is caught in his own trap,†he (Blake) snapped, “which is fitting considering the death he gave to innocent people — but he isn’t dead. He is not escaping the hangman that way.â€

Though one would imagine John Mortimer’s Rumpole, John Dickson Carr’s Patrick Butler, or Sara Woods’ Antony Maitland could get him off on an insanity plea pretty easy with say the help of solicitor Arthur Crook or Joshua Clunk. He’s obviously loony.

The Blake books from this era and into the sixties are often very good with writers like W.A. Ballinger, Rex Hardinge, Hugh Clevely, Jack Trevor Story (The Trouble with Harry), and other relatively familiar names penning them.

They are still pulp, still series pulp at that, and hardly up to the level of most American paperback and digest fiction of the era, but they follow a long tradition and there is nothing to be ashamed of here. They have colorful covers, they are well plotted, there is variety, and they are well written.

No wonder they were still doing Sexton Blake movies and television series well into the 1960‘s.

So, three British pulps from three different eras, all fun to read, all fluff, but good fluff, and all uniquely British in style and outlook. Fans won’t let Sexton Blake die and there are sites devoted to him. You can find actual e-books of Thriller, Blake, and a few Dixon Hawke books on line along with Nelson Lee, Falcon Swift, and Waldo the Wonderman, and the covers are still attractive to look at and worth collecting. (Steve Holland at Bear Alley has done a couple of handsome Blake anthologies.)

The past never really dies, somebody just collects it.

Note: All three of these stories (and many others) can be downloaded and read online at Comic Book Plus.

Fri 18 Jul 2014

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

THE GREAT ST LOUIS BANK ROBBERY. United Artists, 1959. Steve McQueen, Crahanm Denton, David Clarke, Molly McCarthy. Screenplay by Richard T. Hefron. Directors: Charles Guggenheim & John Stix.

The title on the film itself is simply The St. Louis Bank Robbery, so you see how art gets corrupted. The only name in the whole cast and credits you’d recognize is Steve McQueen, which is a shame because this is written, played and directed with unusual insight by all concerned.

And I mean they do a really credible job of bringing out what Chandler used to talk about in terms of a crime and its effect on the characters. It’s as if a bunch of real people were plunked down into a caper film and left to sort out their aspirations and disappointments in the film’s brief running time.

The result compares with the best of the French New Wave films that were coming from the likes of Godard and Truffaut at that time and getting a lot more critical attention. St. Louis languished in oblivion but it’s well worth the few dollars and ninety minutes’ investment it takes.

By the way, in researching this, I found that director Charles Guggenheim, also produced a TV series I’ve never heard of, back in the early 1950s — Fearless Fosdick!

Thu 17 Jul 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

THE RAID. 20th Century Fox, 1954. Van Heflin, Anne Bancroft, Richard Boone, Lee Marvin, Tommy Rettig, Peter Graves, Will Wright, James Best. Director: Hugo Fregonese.

Every once and a while, I happen upon a movie from the 1950s that doesn’t have much of a critical reputation, but is both well made, and eminently watchable. That’s the case with the action/quasi-Western film, The Raid, starring Van Heflin, Anne Bancroft, Richard Boone, and Lee Marvin.

Loosely based on a Confederate raid on, and bank heist in the border town of St. Albans, Vermont, in October 1864 (you can read more about the actual historical events and timeline here), The Raid benefits from a strong cast capable of solid acting, a screenplay bereft of the type of sentimentality that ruins far too many historical dramas, and superb, crisp cinematography by Lucien Ballard, known by Western fans for his work in The Wild Bunch. The choreographed fight scenes, while by no means similar to those in the better-known epic films, are nevertheless quite well constructed.

The movie begins with a good old-fashioned jailbreak. Confederate soldiers, under the command of Major Neal Benton (Van Heflin), break out of a Union prison located close to the Canadian border. Among the men in their ranks is the hotheaded Lt. Keating (Lee Marvin), who you just know is going to cause problems as the story moves forward. The men make their way to neutral Canada and from there put in motion an ambitious plot to raid Union towns on the other side of the border. Among the conspirators is Lt. Robinson, memorably portrayed by James Best.

St. Albans, Vermont is the first target. Benton (Van Heflin) arrives in town, pretending to be a businessman named Neal Swayze. He finds lodging in a boardinghouse run by war widow Katie Bishop (Anne Bancroft) who lives there with her son, Larry (Tommy Rettig). Among the other boarders is a wounded Union soldier, Captain Lionel Foster (Richard Boone), a man with a burdensome secret that haunts his present.

The majority of the movie follows Benton as he interacts with fervently pro-Union members townsfolk, all the while plotting against the small Vermont city. Along the way, he develops a quasi-romantic attachment to the lovely Katie and some fatherly affection toward her son. When Benton stops a violently drunk Keating (Marvin) from shooting innocent people, he inadvertently becomes the town hero. Needless to say, this puts him in an awkward position, as his fellow Confederates, including Captain Frank Dwyer (Peter Graves in a not particularly memorable performance) are ready for action.

The Raid culminates in a fairly violent sequence in which Benton and his men raid the town, rob a bank, and burn down numerous establishments. Former Union officer Foster (Boone) attempts to stop them, in part to make up for his shameful secret. But it’s to no avail. In this film, at least, the South is victorious.

There’s thankfully very little sentimentality here. Benton doesn’t fall madly in love with Katie and abandon his mission. He’s a soldier through and through. There’s something very real about his character, although the scenes in which he is angry upon encountering anti-Confederate sentiment in the town are a bit hard to digest. One would think a spy would be able to hide his true emotions a bit better.

That said, Van Heflin was well cast in this role. He portrays a man conflicted, but one not a man about to abandon his homeland for a fairy tale romance. For his part, Lee Marvin succeeds brilliantly in his portrayal of an alcohol prone Confederate officer more interested in wreaking havoc than in following orders. He’s such a presence that you almost feel bad for the guy when he gets it in the chest. It was a relatively early role for Marvin, but you can see why he was going to have a long career ahead of him.

I’d hesitate to call The Raid a forgotten masterpiece. It’s simply a very good movie, one that has good characters and tells an interesting story. The fact that the film lacks a hero may explain its relative obscurity. It has a protagonist in Benton, but he’s not really a hero. But what if there weren’t any real heroes in the St. Albans raid? Maybe they were just men hundreds of miles from home, swept up in the torrent of a war that they didn’t ask for in the first place. Maybe that’s the whole point.

Thu 17 Jul 2014

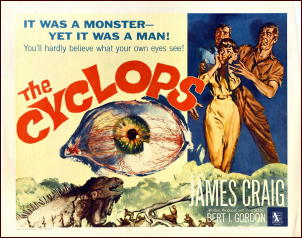

THE CYCLOPS. Allied Artists, 1957. James Craig, Gloria Talbott, Lon Chaney, Tom Drake, Duncan Parkin. Screenwriter-director: Bert I. Gordon.

There is some suspense in this rather mediocre sci-fi movie, but not more than you would want to pay more than a quarter for, as you might have, if you were a kid back in 1957.

It begins with three men and a girl (Gloria Talbott) trying to locate the girl’s fiance,or his body, whose plane went down in a mountainous area of Mexico three years ago, an area so forbidding they are, well, forbidden by local authorities to travel there. Of course, they do so anyway, landing safely (barely) in a small plane built for four.

Turns out that one of the men (a rather dissipated-looking Lon Chaney), who has financed the venture, has an ulterior motive: uranium, and it turns out that the valley where they’ve landed is loaded with the stuff. It also turns out that the valley is chock full of giant beasts. Connect the two facts, and I think you can figure out where this is going right away, but it takes our four adventurers a while. It has to, or else they’d get right back in the plane and get the heck out of there.

They don’t but they soon wish they had. The special effects are awful quite primitive, and the giant guy with one eye is really hokey ugly. The fact that Gloria Talbott is rather fetching, even in coveralls, does not make up for a really inferior work of art on the monster’s makeup job.

The movie, while still mildly entertaining today, was really made for someone who was maybe nine or ten in 1957. Or to be honest, for someone who was nine or ten in 1957 and for whom the nostalgia factor is greater than the judgement of someone seeing it now for the very first time.

Thu 17 Jul 2014

LOST AND FOUND AT YOUTUBE

by Michael Shonk:

PETROCELLI. NBC, 1974-1976. Paramount Television / Miller-Milkis Production. Cast: Barry Newman as Anthony “Tony†Petrocelli, Susan Howard as Maggie Petrocelli, and Albert Salmi as Pete Ritter. Created by Sidney J. Furie and Harold Buchman. Developed for television by E. Jack Neuman. Executive Producers: Thomas L. Miller and Edward K. Milkis. Producer: Leonard Katzman. Executive Story Consultant: Jackson Gillis. Story Editor: Dan Ullman. Music by Lalo Schifrin.

“The Golden Cage.” 11 September 1974. Teleplay by Dan Ullman. Story by Leonard Bercovici. Directed by Joseph Pevney.

Guest Cast: Joseph Campanella, Rosemary Forsyth, Morgan Woodward and William Windom.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z0E3GOvbhDc

This was the series first episode and aired opposite two other new series, ABC’s Get Christie Love and CBS’s The Manhunter. (See my review of The Manhunter here.)

The series featured Anthony Petrocelli, a Harvard-educated lawyer and proud Italian, who decides to leave New York for the small community of San Remo, Arizona, to help the powerless and innocent. The first case involved the abused wife of the richest most powerful man in the county.

Petrocelli would last two seasons.

One note of warning, shows can come and go fast on YouTube and others remain there for years. This is one you might want to hurry to check out.

Wed 16 Jul 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

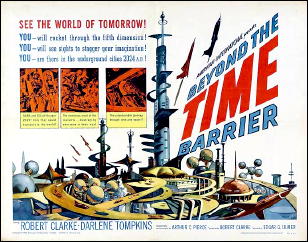

BEYOND THE TIME BARRIER. American International, 1960. Robert Clarke, Arianne Arden, Vladimir Sokoloff, Stephen Bekassy, John Van Dreelen, Boyd ‘Red’ Morgan, Darlene Tompkins. Director: Edgar G. Ulmer.

Beyond the Time Barrier is a low budget science fiction film directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, whose The Amazing Transparent Man I reviewed here. Filmed over a ten days in Dallas at the same time as that rather disappointing film about an invisible bank thief, Beyond The Time Barrier follows U.S. Air Force pilot, Major William Allison (Robert Clarke, who also produced the film) who, after inadvertently breaking the time barrier in his planet, jettisons forward to the year 2024.

As it happens, the society Major Allison encounters is a dystopian one. After landing his plane, he is captured by agents from a city-state called The Citadel. Within its walls are dying remnants of human civilization ravaged by a plague that began in 1971. There are also mutants, but they are far less threatening than the ones in the movie, The Time Travelers, which I reviewed here.

The leader of The Citadel, Supreme, (Vladimir Sokoloff), and his henchman, Captain (Red Morgan), are less than pleased with Allison’s arrival. Fortunately, Supreme’s lovely granddaughter, the mute telepath, Trirene (Darlene Tompkins), has romantic feelings toward the good major and, in any case, she can read his mind and thinks he’s not such a bad guy after all. There’s a budding relationship between these two, but one that never ends up going anywhere. It’s too bad, especially since we learn that Trirene is the only one left alive who isn’t sterile.

The main focus of the film is Major Allison’s quest to find a way to get back to the past, possibly to prevent the future from happening. Aiding him in his endeavor are some Russians from the past who also ended up at The Citadel.

Unfortunately, the film really doesn’t really take the paradoxes of time travel that seriously, making significantly less impressive than it could have been. That said, the ending does demonstrate that the filmmakers understood at least one potential aspect of time travel. There’s also a message about the dangers of atomic testing.

It’s not the standard science fiction B-film plot, nor the somewhat mediocre acting, however, that makes Beyond The Time Barrier worth watching.

Rather, it’s Ulmer’s direction, notably his exceptional use of geometry that makes it worth consideration. Triangles and pyramids are omnipresent in The Citadel. Spheres, both black and white, are also prominently displayed in different locales within the dystopian city-state.

This use of geometry as a replacement for big budget special effects really does pay off. Look for the scene in which Trirene (Tompkins) looks at her reflection in a triangular mirror. It’s not exactly on the same level as the role of mirrors and reflections in Gothic horror films or in films noir, but it’s nevertheless very creative.

In conclusion, Beyond The Time Barrier is a significantly better movie than the disappointing The Amazing Transparent Man. While I wouldn’t go so far as to call it a great film, it’s a perfectly watchable one.

Wed 16 Jul 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marv Lachman

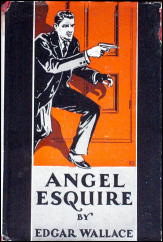

EDGAR WALLACE – Angel Esquire. Arrowsmith, UK, hardcover, 1908. Holt, US, hardcover, 1908. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and soft, including A. L. Burt, US, hardcover, 1927 [shown]. Available online here.

More than eighty years after it was first published, Angel Esquire, Edgar Wallace’s second novel, remains surprisingly readable. Christopher Angel, an eccentric Scotland Yard detective, will remind you of Albert Campion in his early, silly-ass days, but he is often genuinely amusing, as well as resourceful: “Great fellow for putting things right … if you’re in a mess of any kind, Angel’s the chap to pull you out.”

When he’s not working on a case, he sits at his desk working on a racing form, and he is not perturbed at all when the police commissioner comes into his office and finds him so occupied. Angel is the perfect sleuth for a far-fetched mystery involving master criminals, English gangsters, and an intricate puzzle that must be solved before the rightful heirs can receive several million pounds.

Wallace seems to have had fun writing this book. He has a cyanide pellet carried by the villain as a jacket button, and in an inside joke he has Angel play poker with George Manfred, one of the Four Just Men from his first book. He even gives us the type of Tom Swiftie which was so popular in the early 1960’s when he writes of one character’s drink order, “‘Lemonade,’ he said soberly.”

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 3, Summer 1989.

Bibliographic Note: This appears to be the only appearance of Christopher Angel in book form. I have located a story “The Yellow Box” from The Story-Teller, March, 1908, available online here, so there may be more.

« Previous Page — Next Page »