July 2015

Monthly Archive

Sun 5 Jul 2015

COLLECTING PULPS: A Memoir, Part 15:

Death of a Collector: STEVE KENNEDY

by Walker Martin

A friend informed me of Steve Kennedy’s death around 4:00 pm earlier yesterday, and I’ve had problems accepting the news. I last heard from Steve a few weeks ago and at that time he was under a lot of stress due to his attempts to sell his NYC apartment and finish building his dream house in Woodstock, NY. He had been talking to me about both projects for many years and he hoped the money from the apartment sale would finance the completion of the Woodstock house. He had suffered some type of health problem a couple years ago which showed that his blood pressure was very high, and my impression was that he did not seem well.

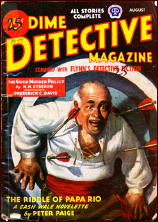

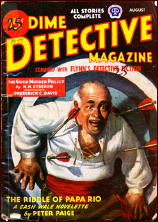

I still remember my first sight of Steve as though it was only the other day. It was 1987 and he was in the Pulpcon dealer’s room carrying around a cover painting by Rafael Desoto from Dime Detective. He wanted to sell it but was getting no interest at all from the pulp collectors. This was a common reaction in the 1970’s and 1980’s when most pulp collectors were only interested in SF or hero pulp art. If the paintings were from western, detective, or adventure magazines, then there was usually no interest at all even if the price was low.

I know it’s hard to believe now when these paintings often sell for thousands of dollars but back then you could not even get offers when the price was only a few hundred dollars each. The only exceptions were SF and hero magazine covers. I know this for a fact because I built my pulp cover painting collection by paying only $200 to around $400 each for most non-SF genre paintings. In the 1990’s I had to start paying more and eventually due to the prices that Bob Lesser was willing to pay, the cost of pulp paintings really increased.

Since no one was willing to buy the Desoto painting, I bought it for only $325 in 1987. That began our 28 year friendship during which Steve sold me many paintings including some by Norman Saunders, Rafael Desoto, Walter Baumhofer, etc. Even a couple years ago when I told him I wanted a double page spread by Nick Eggenhofer, he sold me a beautiful drawing from the collection of art dealer, Walt Reed.

As I walk through my house, almost every room has paintings that I bought from Steve over the years. He visited my house several times each year for a total of over a hundred visits. Several times we drove out to Pulpcon together in my car. He would arrive the day before and sleep over due to my habit of getting an early start to drive to Pulpcon.

Steve was the only collector that my wife would put up with staying over because he at least dealt with art and paintings and was not covered with pulp chips from the magazines that so exasperate her. Steve and I both felt that there was nothing wrong with a house full of old magazines and books, not to mention pulp and paperback cover paintings!

We often told each other funny stories about non-collectors and in addition to the many visits, we had hundreds of telephone conversations, many late at night at around midnight. Since Steve did not work regular hours being self employed, he often called me late which I had no problem with because I’m always up late during the night reading books and pulps.

The wedding of Steve Kennedy and Jane came as a surprise to all his friends because he was always puzzled by NYC women and was in his 50’s when he got married in 2001. I guess Jane was really not from NYC. The wedding was held at Jane’s parents place in Woodstock, NY and was without a doubt the best wedding I ever attended. Not just the food and atmosphere but they had two bands: a Brazilian jazz group and two classical guitar players.

One funny thing about Steve getting married was that since he had been a bachelor for so long, he was scared of finally getting married. So much so that he called me in a nervous attack one night and asked me to give my opinion. Should he get married? I of course said sure go ahead because Steve was an art dealer and Jane was an art appraiser. Not the typical collector and non-collector disaster!

So, I’m still trying to process the information. Steve Kennedy is gone? No more visits, no more late night phone calls? No more trips to Pulpfest or Windy City? Another of my old friends gone for good? This is hard to believe that someone so much a part of my life can simply disappear.

Goodbye Steve. R.I.P.

Sat 4 Jul 2015

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

TARZAN’S MAGIC FOUNTAIN. RKO Radio Pictures, 1949. Lex Barker, Brenda Joyce, Albert Dekker, Evelyn Ankers, Charles Drake, Alan Napier. Based upon the characters created by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Director: Lee Sholem.

While I doubt that many people would consider Tarzan’s Magic Fountain to be their favorite Tarzan movie, that doesn’t mean that it’s not perfectly adequate cinematic escapism.

Directed by Lee Sholem, the movie was Lex Barker’s first appearance as the eponymous title character. As for Brenda Joyce, this would be here final appearance as Jane, having portraying Tarzan’s love interest in four movies with Johnny Weissmuller.

Tarzan’s Magic Fountain is also notable for featuring Evelyn Ankers, best known for her work in 1940s-era horror films. Ankers portrays Gloria James Jessup, an aviatrix whose plane crashed in the jungle decades before.

For years, Jessup had been living with a secretive tribe who control access to – you guessed it! – a secret fountain with restorative powers. As in, fountain of youth powers that make her look a lot younger than fifty. But when scheming criminals get word of the fountain’s existence and when some tribesmen decide they don’t like Tarzan mucking around, there’s conflict and when there’s conflict, there’s adventure to be had. It’s predictable, but it’s not bad.

Fri 3 Jul 2015

Reviewed by DAN STUMPF:

RICHARD MATHESON – The Gun Fight. M. Evans, hardcover, April 1993. Forge, paperback, November 2009.

It’s a nail-biter.

A lean, taut tale of three days in a small Texas town when a rumor gets out of control and a deadly ex-lawman finds himself called out to kill an impulsive youngster in “an affair of honor†based on nothing but gossip.

Now I have to say here that I don’t know much about Gossip because I never engage in it; when I hear a second-hand story that reflects discredit on someone (usually Steve) I just discuss it with ten or twelve people and see what they think. But I have to say that Richard Matheson paints a vivid word-picture of a false report taking on a life of its own as it grows and feeds on itself and human nature.

Along the way he also generates a whole lot of tension as we see the various characters move away from tragedy and lurch back toward it again, the effect enriched by Matheson’s skill at sketching out characters quickly, vividly and believably. There’s not a whole lot of action here, but I think you’ll find The Gun Fight impossible to put down.

Thu 2 Jul 2015

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

For no reason I can put my finger on, I recently felt an urge to reread some of Dashiell Hammett’s shorter work. Again for no particular reason, my starting point was not a Continental Op story but “The Assistant Murderer,†which was first published in Black Mask for February 1926 and is most easily accessed today in Hammett’s Crime Stories & Other Writings (Library of America, 2001).

In his only published exploit, spectacularly ugly Baltimore PI Alec Rush is retained by a young banker to find out why someone is shadowing a gal he’s sweet on but was forced to fire. Soon Rush discovers that the shadow has been paid by two different women to kill the gal in question.

From there the plot gets more convoluted by the minute. The journal I kept in my salad days tells me that I first read this novelette early in 1965, not long after my 22nd birthday and during my first year in law school. Back then I loved it. Half a century later I still like it but perhaps with a bit less enthusiasm.

What I found most interesting today is not so much the plot or characterizations or style but the legal aspects. Which, like those of another Hammett story I discussed in an earlier column, leave something to be desired.

To explain where Hammett went off the tracks requires me to spoil some of the plot, but I’ll try to minimize the spoliation by translating the situation into a sort of law examination question. A, who died long before the story begins, left an estate of roughly $2,000,000, a princely sum back in the early 20th century and not to be sneezed at even today.

He had two sons, B and C. His will created a trust excluding B, whose lifestyle he disapproved of, and naming C as sole income beneficiary. The will specified that C was free to share the income with B to whatever extent he chose, which he would have been free to do anyway.

Typically for a Hammett character, C had chosen to keep the entire income for himself. B dies, a widower survived by a daughter whom we’ll call D. Under A’s will, on C’s death the corpus of the trust is to be divided among A’s grandchildren. Since C is unmarried and childless, this means that on his death everything will go to D. As chance would have it, D is married to a sort of Iago figure who manipulates her into killing Uncle C.

The husband’s scheme doesn’t require that his wife D be tagged for the murder but whether she is or isn’t leaves him cold. “If they hanged her,†he tells Rush at the climax, “the two million would come to me. If she got a long term in prison, I’d have the handling of the money at least.â€

Wrong, Dash! If D were to be convicted of C’s murder, the old common-law maxim that you can’t profit by your own crime would come into play, and the A trust fund would wind up by intestate succession in the hands of various remote relatives of whose identity Hammett tells us nothing. In the absence of such relatives, the fund would probably end up in the coffers of the state of Maryland by a process known as escheat.

But suppose D were only suspected of the murder. Suppose she were never tried for it, or were tried and acquitted, or were convicted but had her conviction overturned on appeal? Could those remote relatives or the state of Maryland sue to divest her of the inheritance in civil court, where her guilt would have to be proved by a mere preponderance of the evidence, not beyond a reasonable doubt as in a criminal trial?

You may well ask! I used to throw out that kind of question to my class when I was teaching Decedents’ Estates and Trusts, but this column is already sinking under the weight of legalese and I won’t deal with that issue unless someone asks me to.

Another aspect of “The Assistant Murderer†that intrigued me was: How many turns of phrase in this almost 90-year-old story need to be explained to readers today? At one point a lowlife tells Alec Rush that “A certain party comes to me with a knock-down from a party that knows me.â€

The Library of America editors explain that a knock-down is slang for an introduction. But a few pages further on, Rush says: “I can see just enough to get myself tangled up if I don’t watch Harvey.†There is no character named Harvey in the story. Did the Library of America people feel that the meaning of this phrase would be clear to readers?

It certainly wasn’t to me. But googling the two words along with Hammett’s name led me to A Dashiell Hammett Companion (Greenwood Press, 2000) by Robert L. Gale, who calls it “an inexplicable reference.†I concur. And in caps!

Let’s migrate from one end of the crime spectrum to the other. I scrutinized every line of James E. Keirans’ John Dickson Carr Companion before it was published but somehow I missed the absence of one Carr adaptation that Keirans missed too. Among the flood of TV PI shows that followed in the wake of Peter Gunn was Markham (1959-60), a 30-minute series starring suave Ray Milland as lawyer-turned-private-investigator Roy Markham.

Most of the scripts for the 59 episodes of this series were originals but a few were based on published short stories by well-known writers — including Ed Lacy and Henry Slesar — and one was adapted from a Carr radio drama. In “The Phantom Archer†(March 31, 1960) an English nobleman calls on Markham to help fight a ghostly archer who is roaming the halls of a historic manor.

Carr’s radio play of the same name was first heard on the CBS series Suspense (March 9, 1943) and the script was published in EQMM for June 1948 and collected in The Door to Doom and Other Detections (1980). Who directed and scripted this Markham episode remain unknown but the cast included Murray Matheson and Eunice Gayson. There are eleven references to “The Phantom Archer†in the index to Keirans’ book but there should have been a twelfth.

Wed 1 Jul 2015

FILM ILLUSIONISTS РPart One: Georges M̩li̬s

by Walter Albert

One of the “givens” of film history is that French director Georges Méliès, a magician who turned his talents from stage to film enchantments, is one of the great film innovators. In my surveys of French films, I have always dutifully shown Méliès’ Trip to the Moon (1902) and talked glibly of the importance of his work.

I was only repeating standard film history, and I had no real basis for believing it until this past weekend when I attended an extraordinary event sponsored by the film section of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Institute.

Méliès’ granddaughter, Madeleine Malthète-Méliès, came to Pittsburgh to present three different programs of his films with piano accompaniment by Eric Leguen. I was able to see thirty-one of the forty-seven films she screened, including four that were hand-tinted, and what I saw on those two rainy, chilly October evenings was a revelation.

In the dozen years from about 1898 to 1910 that Méliès was producing and directing, he made over five hundred short films. His family has been able to assemble and restore only about 150, so the series we were shown represents about one third of the surviving films.

Working before the era of the feature-length films that were to dominate world production after 1912, Méliès drew on his experience as a stage illusionist and his incomparable visual imagination.

Disguises and transformations abound in his films, and he devised the dissolve, fade, and superimposed image to make his fantastic tricks possible. The prints are not always properly defined, and some of them are not complete, but the witty inventions from his apparently inexhaustible box of illusions are still a delight.

What is particularly striking about Méliès’ films is their pacing, a perfectly choreographed comic rhythm that is most impressive when Méliès himself is performing.

For director-producer-writer Méliès was also a comic actor of rare skill, with a good-natured pleasure in fooling an audience that is still infectious after eighty years. He was very fond of playing the role of the Devil, and the final film of the series, Satan in Prison (1907), was a perfect capstone to the screenings.

In this dazzling film, the Devil-Méliès furnishes a bare cell out of his cape, complete to a lovely lady toasted at a candlelight midnight supper. When they are surprised by her jealous husband, she collapses into a heap of crumpled fabric in one of the most magical of Méliès’ effects.

Then, in a furious reverse movement, the Devil strips the room and, disappearing behind the cape, leaps toward the rear wall where the cape suddenly hangs suspended from two nails and, when it is pulled down, exposes a bare wall.

I mentioned to Madame Malthète-Méliès my pleasure in her grandfather’s good humour, and she replied — her entire face lighting up — that even after he had lost everything else, he never lost his humour and was always playing the prankster, pulling innumerable cigarettes out of her ear.

In his last years (he died in 1938) Méliès operated a toy shop in one of the Parisian train stations, but what find most painful is the anecdote of the evening that Méliès burned all of his negatives in the garden of his Montreuil home. Fortunately, prints have survived, but those wasted years when he was eclipsed by a generation of gifted comedians — all of whom drew upon his routines and inventions — is, I think, one of the great tragedies of film history.

— Reprinted from

The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 6, No. 6, November-December 1982.

« Previous Page