From her 2010 CD of the same name:

Drums – Joe Farnsworth

Piano – David Hazeltine

Tenor Saxophone – Eric Alexander

Trumpet – Jim Rotondi

Vocals – Alexis Cole

Wed 25 Nov 2015

From her 2010 CD of the same name:

Drums – Joe Farnsworth

Piano – David Hazeltine

Tenor Saxophone – Eric Alexander

Trumpet – Jim Rotondi

Vocals – Alexis Cole

Tue 24 Nov 2015

W. H. HODGSON “The Thing Invisible.” First published in The New Magazine, January 1912. Reprinted in Carnacki, The Ghost Finder (Eveleigh Nash, UK, hardcover, 1913; Mycroft & Moran, US, hardcover, 1947).

W. H. Hodgson’s Edwardian occult detective story, “The Thing Invisible†may well be considered, at least by contemporary aesthetic and literary standards, a rather quaint foray into the realm of supernatural investigations.

Written in an engaging narrative style, this story is one of Hodgson’s Carnacki detective tales featuring the eponymous sleuth tasked with investigating the arcane and the bizarre. Carnacki, as a investigator of the paranormal, is all too human and more than willing to admit that he’s far from a fearless protagonist. Indeed, what makes Carnacki such an engaging personality is that he’s more than willing to admit that the unknown is capable of frightening him.

In “The Thing Invisible,†Carnacki recounts a case in which he faced down a mysterious dagger that seemed to act on its own accord, a death tool that nearly murdered a family’s butler. As a method of sleuthing, Carnacki makes use of early photography, going so far as to take surreptitious photos which he then uses to solve the puzzle of how a dagger could seemingly float mid-air and attack a man.

Although Hodgson’s writing doesn’t invoke the cosmic dread quite to the same degree that Algernon Blackwood’s work does so effectively, it nevertheless does impress upon the reader a sense of creeping otherworldliness and subtle terror. Even more so, given that in this story at least [SPOILER ALERT], the seemingly impossible events have a mechanical, rational explanation.

Tue 24 Nov 2015

GORDON McALPINE – Woman With a Blue Pencil. Seventh Street Books, trade paperback original, November 2015.

Sam Sumida, a Japanese American academic living in LA on the eve of Pearl Harbor finds himself forced to turn private eye to investigate the murder of his wife by a white man: Jimmie Park is a Korean American agent battling an operation of the Japanese Fifth Columnists (*) in Los Angeles just after Pearl Harbor.

Both Sam Sumida and Jimmie Park are characters in the same novel by Nisei Takumi Saito: the Sumida novel the one he was writing before Pearl Harbor and December 7th 1941, and the Park novel the revised post Pearl Harbor form of the novel resulting from his correspondence with Maxine Wakefield, an editor who is determined to model Saito’s novel into a successful book, even if she has to destroy any sense of Saito’s Japanese identity and turn his book into a pulpish spy novel written under a Caucasian pen name.

We read the story in alternating chapters from the two very different novels within this novel that parallel each other. The Woman With the Blue Pencil is at least three novels in one: the increasingly paranoid and schizophrenic private eye novel being written about Sam Sumida; the pulpish Jimmie Park spy novel being sanitized of any hint of Japanese identity: and, the story of Takumi Saito, told only in the correspondence of Maxine his editor as she blue pencils his Nisei identity out of existence in his work and even his life.

Maxine is the novel’s unlikely femme fatale, her seduction of the young author as real as that in any boudoir or dive, and her blue pencil as devastating as any black negligee or low cut gown in any noirish novel.

The Woman With a Blue Pencil works on several levels, not the least of which is the Sumida private detective novel spiraling into schizophrenia and identity loss. The writing is assured, the manipulation subtle, and McAlpine wisely lets Takumi’s story tell itself.

Maxine is presented as a realistic editor, not a monster, her almost motherly advice at one both right for the time and deadly to the artist and his work. It is a subtle statement about how society, represented by Maxine and the world of publishing, can seduce anyone to fit in while the world around them spiraling out of control, as well as a commentary on the plight of the artist in the market.

I won’t say this is for everyone. I was a bit wary of it when I started, fearing it would be yet another didactic arty attempt to use the mystery form as a statement with no understanding of the form or love for it. But McAlpine, who previously wrote Hammett Unwritten, is well aware of the form and keeps a sure hand in a relatively short novel that is all the better for its brevity. With today’s headlines, the book is all the more contemporary in dealing with the difficulty of maintaining identity in an unpopular minority in a society in crisis and panic.

(*) Since the book does not mention it, it needs to be pointed out that no Nisei, Japanese American, has ever betrayed this country before or after WWII. Despite urban legends to the contrary, no Nisei here or in Hawaii committed any act of treason or sabotage even after the Internment of Japanese Americans on the West Coast — more than can be said for German or other immigrants born here then or later.

Tue 24 Nov 2015

Carolyn Wonderland is a Texas-based blues singer-songwriter. “Only God Knows When” is a track on her 2011 CD Peace Meal.

Mon 23 Nov 2015

NICHOLAS KILMER – Dirty Linen. Henry Holt & Co., hardcover, March 1999. Poisoned Pen Press, softcover, March 2001.

MICHELLE BLAKE – The 8ook of Light. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, hardcover, May 2003. Berkley, paperback, May 2004.

Both these books are by authors I’ve not read before and feature plot hooks that I can’t resist: an art historical mystery (Dirty Linen) in which a batch of J. W. M. Turner drawings turn up in a country auction; and, in The Book of Light, the discovery of an ancient document, the “Q” manuscript that was purportedly the source for much of the biblical texts of Matthew and Luke. But apart from irresistible hooks, they couldn’t be more different.

In Kilmer’s book, Fred Taylor is an agent for Boston collector Clayton Reed charged to bid on a lot at a benefit auction. Fred has no idea what is in the lot and when it turns out to be a series of erotic drawings by the English landscape master Turner, he finds himself enmeshed in a dangerous web of murder and attempted murder that has him trying to trace the history of the contested works in an attempt to establish the provenance of the drawings and thwart other murders.

Blake’s compelling theological thriller plays out in a constricted setting dominated by Lilly Connor, an Episcopalian priest filling in as a Boston area college religious counselor, who’s asked to validate a manuscript, which she comes to suspect may be the legendary Book of Light, a collection of the transcribed words of Jesus, rather than the “Q” document.

Kilmer’s novel is a raunchy, humorous caper. Blake’s stylistically acute novel is a record of souls in anguish, with a centuries old secret group committed to guarding the secrets of the ancient document that places Lilly’s small frightened group in extreme peril.

I’ll undoubtedly return to both writers, but my expectations will be higher for Blake than for Kilmer.

Mon 23 Nov 2015

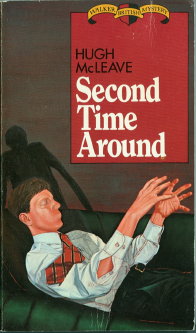

HUGH McLEAVE – Second Time Around. Walker, US, hardcover, 1981; paperback, 1984. First published in the UK by Robert Hale, hardcover, 1981.

According to Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, five of Hugh McLeave’s works of thriller fiction (one as by Richard Copeland) feature as their leading protagonist, free-wheeling psychologist Dr. Gregor Maclean, who, as a leading character in Second Time Around, takes on what is very nearly a secondary role.

On the other hand, a psychologist is exactly who is needed at the center of this Cold War tale about a reputable London publisher who on occasion checks into various clinics with no memory of who he is or why he is having such terrible dreams.

Maclean becomes interested when Dr. Armitage, a close acquaintance who was treating the man, gets run down by an automobile after confiding his concerns to Maclean, but in the stark, documentary-like style of writing that McLeave employs, Maclean seems to exhibit no great anguish over Armitage’s death – only the delight of tackling the puzzle it seems to supply.

Here’s a longish quote from pages 32-33 to illustrate. Deidre is Maclean’s long-suffering live-in assistant:

“Macushla, just look at him as a patient,†he pleaded.

The case – and yes, he certainly does decide to get involved – takes Maclean, Deidre, the publisher’s daughter, and a male friend of the daughter, not to mention at least one other – on a hastily arranged trip to Germany, both East and West, on the trail of the man whose memory is either coming back — and if so, from what hidden past? Or he is cracking up completely and probably responsible for the deaths of several prostitutes who reminded him of whom?

Second Time Around verges very closely into science fictional territory, mixed in with a considerable amount of bitter cold war philosophy. But is the basis of the book based entirely on fiction? Very likely not.

Nor is this a book which is like anything I have ever read before. It is clear more quickly to the reader what the underlying circumstances are (which I am being so careful not to tell you about) than they are to Maclean. This may be an error, perhaps, on the author’s part, because the tale starts to plod a little, about two-thirds of the way through.

After reading this book I still prefer the more solid espionage efforts of Ross Thomas and Manning Coles, two writers who otherwise have little in common – or do they? – but I have to admit that, one, McLeave still has a small surprise or two up his sleeve, and, two, this very well may be one of the saddest love stories ever written. Is that enough for a recommendation? Either way, it will have to do.

Mon 23 Nov 2015

Sun 22 Nov 2015

TALMAGE POWELL – With a Madman Behind Me. Permabook M-4233, paperback original, 1961.

Whenever I see a nice-looking paperback original mystery under 50 cents I pick it up whether I know anything about the author or not, and Talmage Powell’s With a Madman Behind Me turned out to be a readable blend of the preposterous and the pretentious. No classic, maybe, but I didn’t throw it across the room, either.

It opens with PI Ed Rivers looking out his window one hot Tampa night to see a woman in an apartment across the way waving for help. He gets to her place just in time to:

a) See her killed

b) Learn the identity of her killer

c) Get a clue that will bust open a devious plot to flood America with (gasp!) pornography

d) Get knocked out, tied up and dumped in Tampa Bay.

That’s the Preposterous part. The Pretentious comes right on the heels of this, when everyone starts talking like freshman sociology students: as when a Homicide cop describes a dead hooker:

And a few pages later Ed Rivers confronts a witness and describes her:

It turns out even the bad guys talk this way, as a Porn kingpin tells Ed:

Now I ain’t narrow-thinking, but a man gets tired of that kind of talk all the time. And there’s plenty more of it here. It’s as if author Talmage Powell read a Travis McGee book and never got over it.

On the plus side, however, Powell handles the action scenes well enough, moves the predictable plot along swiftly, and does not — as some authors do — deplore the art of pornography, then proceed to fill his book with sex. There’s even a sort-of pay-off for all the over-analyzing, as the book wraps up with a thoughtful twist on an old plot.

It’s not enough to save Madman from utter forgetabilty, but it does provide a readable time-waster for those who miss the old days of paperback crime.

The Ed Rivers series —

The Killer Is Mine (1959)

The Girl’s Number Doesn’t Answer (1960)

With a Madman Behind Me (1961)

Start Screaming Murder (1962)

Corpus Delectable (1964)

Sun 22 Nov 2015

TREASURE ISLAND. National General Pictures, US, 1972. Filmed in Spain with a Spanish crew. Orson Welles, Kim Burfield, Lionel Stander, Walter Slezak, Ãngel del Pozo, Rik Battaglia. Directors: Andrea Bianchi (as Andrew White), John Hough (English language version), Antonio Margheriti.

I had somewhat high hopes for Treasure Island, but I probably should have known better. It’s probably one of Orson Welles’ least known films and it’s most certainty that way for a reason. Produced by Harry Alan Towers, this somewhat genial, but ultimately unsatisfying adventure yarn based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic novel features the legendary Welles as Long John Silver.

Welles, whose pirate voice may or may not have been dubbed by another actor, grunts and slurs his way through this plodding affair. Even Walter Slezak, who ordinarily is a standout actor, falls somewhat flat – pun intended, if you’ve seen the movie – as Squire Trelawney.

Young actor Kim Burfield, who portrays Jim Hawkins, is somewhat more of a presence, portraying the narrator/protagonist with wide- eyed charm and glee. Jim’s sense of wonder and excitement is, at the end of the day, what propels this somewhat tired affair. But to no avail. Overall, the movie leaves the viewer with the distinct impression that at another time, with another director, Welles really could have thrived and shined as the legendary fictional pirate cook.

Sun 22 Nov 2015

From the LP Banned in Boston: