From violinist and lead singer Rani Arbo’s 2001 release Cocktail Swing, her group’s first CD:

May 2016

Thu 19 May 2016

Music I’m Listening To: RANI ARBO & DAISY MAYHEM “I Get The Blues When It Rains.”

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening ToNo Comments

Wed 18 May 2016

FRANK KANE – Poisons Unknown. Ives Washburn, hardcover, 1953. Dell 822, paperback, 1955; Dell D334, paperback, January 1960.

This is the seventh of 29 Johnny Liddell PI novels plus two short story collections. Liddell’s career started way in 1944 with the story “Murder at Face Value” appearing in the January 1944 issue of Crack Detective Stories, not the highest level of pulp magazines but it was a start. His first appearance in hardcover was About Face, published by Mystery House in 1947.

In Poisons Unknown, Liddell heads for New Orleans to find a Holy Roller preacher in flowing white robes who’s gone missing. Liddell is working for a mob boss whose crime and corruption Brother Alfred has been sermonizing heavily against. If Alfred is dead, Marty Kirk fears he will be blamed.

Or is Kirk just using Liddell to set up and eliminate Alfred? That’s what has Liddell puzzled. There is a twist or two, maybe three, in the story that follows, but only one may come as a surprise to anyone who’s spent their lifetime reading old PI novels such as this one.

All in all, this one’s no more than average but far from mediocre and not nearly as formulaic as Kane was later, only mildly sex-obsessed but interrupted every so often by highly choreographed violence, and easily forgotten by the next morning.

Wed 18 May 2016

A Movie Review by Jonathan Lewis: DIAL 1119 (1950).

Posted by Steve under Crime Films , Reviews[4] Comments

DIAL 1119. MGM, 1950. Marshall Thompson, Virginia Field, Andrea King, Sam Levene, Leon Ames, Keefe Brasselle, Richard Rober, James Bell, William Conrad. Director: Gerald Mayer.

There are a few things about Dial 1119 that make it particularly unique. Most noticeably, the film is largely bereft of any music, background or otherwise, giving it a rather somber, claustrophobic atmosphere. Which is fitting given the film is about an escaped murderer named Gunther Wyckoff (Marshall Thompson) holding a ragtag group hostage at a neon-lit watering hole.

The sensibility is pure noir, as one cannot help but feel the undercurrent of despair and hopelessness. Lurking in the background are the aftereffects of the Second World War and its impact on postwar American society.

Also adding to the film’s uniqueness are two additional elements that, in my estimation, work in its favor.

First, the cast largely consists of actors and actresses who weren’t top billed names in the business. Crime film fanatics will surely appreciate Sam Levene and William Conrad. But neither of them is present in the movie for very long. Instead, the focus is really front and center on Marshall Thompson, who you may recognize from the sci-fi classic, It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958). Trust me when I say that he’s very good in this and plays his part to the hilt. There’s something about his expressionless face that makes his character particularly memorable.

Second, the film serves as a seething and prescient indictment of news media saturation in which tragic events are transformed into spectator sports designed for mass public consumption. Like many of the best crime films, Dial 1119 tells us as much about the society that produced the criminal as the criminal himself.

Overall, Dial 1119 is worth a look. I didn’t know all that much about the movie going in, but after watching it, I can easily imagine myself returning for a second viewing sometime in the years ahead.

Tue 17 May 2016

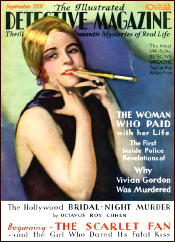

A Magazine Review by David Vineyard: THE ILLUSTRATED DETECTIVE MAGAZINE – September 1931.

Posted by Steve under Magazines , Reviews[9] Comments

THE ILLUSTRATED DETECTIVE MAGAZINE. September 1931; 10¢, 122pp, 9″ x 12″.

This slick magazine distributed through Woolworths and published by Tower Books, is surely one of the strangest detective magazines of that or any other era. The full title includes The Illustrated Detective Magazine, Thrilling and Romantic Mysteries of Real Life, billed as “The Most Unusual Detective Magazine You Can Buy at any Price.â€

The magazine was aimed at women running from 1929 to 1932 and changed its title after thirty three issues to Mystery. Not all the stories are romantic in nature, though the bias in favor of women readers is fairly evident.

The Illustrated Detective Magazine is an odd mix of disparate material. There are true crime and confession-style articles like “The Woman Who Paid With Her Life†by ‘a Police Official’ about the murder of blackmailer Vivian Gordon; “The Iron Czar†by Jim Roberts about early New York gangster Iron Man Becker; and “He Risked All for the Thrilling Chance,†asking what happened to the crusading detective/reporter of an earlier age, as well as beauty and cooking aids and articles on scientific detection.

The issue’s fiction opens with a story called “Received Payment,†unbilled to any author but described as ‘another’ crime busting account of Mary Shane, who turns out to be an attractive semi-independent sleuth in this case helping to put bootleggers out of business who sell poisoned bathtub gin. It’s a fairly tough little story and Mary Shane tough as nails in her underworld dealings, if not particularly realistic or believable. It’s closer to the dime novel than hard boiled. This and some other features are illustrated with dramatized photographs while some have black and white illustrations, mostly handsomely done in wash rather than line, thanks to the slicker paper.

This issue features the opening installment of “The Hollywood Bridal Night Murder†by Octavius Roy Cohen, featuring his popular fat jovial canny sleuth Jim Hanvey. Cohen was a sure seller on the front of magazines of the period, and Hanvey was popular enough to have two film outings. It’s standard Cohen fare, meaning entertaining but nothing special. You won’t be all that driven to find the later installments or the book publication unless you are an obsessive sort.

The second big story in the issue is “The Egyptian Necklace†by R. T. M. Scott, an adventure of Aurelius Smith, a private detective who would form the basis for Richard Wentworth and the Spider when Scott wrote the first entry in that series. While the story is dated, it shows the strengths and weaknesses of the Smith series and Scott’s writing, and is the most pulp-like of the stories in this issue. It’s probably the story most readers here will enjoy the most, with its hints of melodrama and mystery from the East.

Major fiction entry number three is a humorous tale by Ellis Parker Butler, “The Heckly Hill Murder†featuring ‘Oliver Spotts, the Near Detective of Mud Cove, Long Island.’ It is a moderately amusing romp by a well known humorist of his time, but mindful too that whimsey doesn’t always survive the passage of time. It shows Butler’s talents to good effect but how a modern reader reacts to it is anyone’s guess.

The rest of the magazine includes a sort of fictionalized expose called “The Queen of the Beggars†by James Jeffrey O’Brien, about a young man who runs afoul to the beautiful and dangerous self styled ‘queen’ of the big city beggars. There are also some rather sensational ‘true confession’ pieces, a bit on code-breaking, a plea and offer of a $1,000 reward for information leading to the discovery of Judge Crater, and articles on fingerprinting and other aspects of police work, interspersed with ads for Woolworths, articles sold at Woolworths, and publications of Tower Books.

All in all it is a very odd little magazine, but a pretty good bargain for a dime if you happened to be shopping in Woolworths. This was the third issue, and it continued until 1932 in more or less the same vein. It is certainly one of the stranger magazines of its type I’ve run across.

Tue 17 May 2016

Music I’m Listening To: GUY CLARK – Texas Cookin’.

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening To[2] Comments

Here’s the title track from this Texas singer-songwriter’s second album (RCA, 1976):

Mon 16 May 2016

A Book! Movie! Review by Dan Stumpf: SEBASTIEN JAPRISOT – The 10:30 from Marseilles / THE SLEEPING CAR MURDERS (1965).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[3] Comments

SEBASTIEN JAPRISOT – The 10:30 from Marseilles. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1963. Pocket, paperback, 1964. Souvenir Press, UK, hardcover, 1964. Originally published as Compartiment Tueurs, Paris, 1962; translated into English by Francis Price.

THE SLEEPING CAR MURDERS. Fox, 1966. First released in France, 1965, as Compartiment tueurs. Yves Montand, Simone Signoret, Jean-Louiis Trintingnant, Michel Piccoli, Catherine Allegret and Jacques Perrin. Written and directed by Costa-Gravas.

Two approaches to the same story, with striking differences.

In the book, the 10:30 a.m. train from Marseilles pulls into Paris and the guy who cleans out the cars finds a dead woman, strangled in her berth (one of six) in a sleeping car. The Police begin their investigation at the logical place: find out who else was in that compartment and see what they know.

Inspector Graziani and his assistant Jean-Lou get the unenviable assignment of tracking them down, with the dubious help of their superior, a sub-chief who likes to talk in pithy but useless aphorisms (“Cover everything. It’s always where you don’t look….â€) whereupon….

We cut to Berth 226 and the man who used it last night: What he was doing there, how he interacted with the other passengers, and his reaction on finding out the Police want to talk to him. Then, as he rehearses his story, someone comes up from behind and shoots him.

Graziani and Jean-Lou, meanwhile, are still running down leads and find themselves with a problem: One passenger tells them there was a berth unoccupied; another passenger insists there was a man in it; and the woman who bought the ticket maintains she was there all night.

Then we cut to another Berth and the woman who used it; what she was doing on the train, what she saw there, and a long bit about her background. She tells the Police everything she knows, and after they leave, someone comes up from behind and shoots her.

And so it goes as we follow the investigating officers, then switch to another passenger… who also ends up dead. And then another. And then… well, you get the idea; someone is killing everyone who was on the train that night. But why? And how is the killer finding them?

Then, as we’re running out of berths, the pattern breaks and we get the answer to the riddle of the not-empty bed. We also get a charming tale of young love and youthful idiocy, mixed with a tense cat-and-mouse between the police, the killer, and his last victim.

Japrisot’s puzzle is a tricky one, and I applaud his craftsmanship, but I have to say things tend to drag a bit when he details the lives of his passenger/victims. It’s as if he’s more interested in the puzzle than the characters — and it shows.

Costa-Gravas’s film suffers from something similar; things drag seriously when he gets into the minutia of the characters involved, but he manages to save the effort with some sly visual tricks and camerawork that manages to be stylish without showing off.

Interestingly, he also chooses to reconstruct the story in linear fashion. We start with everyone getting on board before the murder, see them interact, understand the problem of the empty berth right from the start, and get involved with the young klutzes who end up being pursued by the killers.

Yves Montand has the dog-weary look appropriate for a police detective, and Simone Signoret radiates her usual overstuffed star power, but the most interesting performances come from Catherine Allegret and Daniel Perrin as a pair of youngsters caught up in the machinations of Japrisot’s tricky plot. Together they convey the kind of emotional reality one finds in the best films of Francois Truffaut, and I found myself wanting to see more of their affairs and less of the murders, well-done though they are.

And one other nod to cinematic convention: Where the book wraps up with off-page arrests, interviews and confessions, the movie ends with a car chase and shoot-out; well done, but I still wanted to see more of those crazy kids.

Mon 16 May 2016

Archived Mystery Review: MICHAEL INNES – The Case of Sonia Wayward.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[3] Comments

MICHAEL INNES – The Case of Sonia Wayward. Dodd Mead, hardcover, 1960. Reprinted several times in paperback, including Penguin, 1972. First published in the UK as The New Sonia Wayward (Gollancz, hardcover, 1960).

It begins with Sonia dead, no mourning her. She had been a prolific writer of romances, trifles to be sure, but quite popular with certain segments of the population, and quite naturally Colonel Pettigate, her husband of long standing and forbearance, finds the need to carry on without her.

As he blithely blithers his way through her unexpected absence, leaving gaping holes carelessly strewn as he passes, he does manage to complete Sonia’s latest work-in-progress, giving rise as he does so to a good deal of deft tongue-in-check tomfoolery about the mysterious ways of artistic creation.

But at length blackmail and the social graces suggest that Sonia’s return, for at most a week, say, would do wonders for the colonel’s growing embarrassments. Of course there’s an obvious way out — an impersonation? — one that not even the colonel can miss.

It ends as a high-brow comedy, delicious and wholly captivating, though I shouldn’t say that many will be at all surprised with the ensuing vicissitudes of fate. Innes prepares us for them especially well in advance.

Rating: A minus.

Sun 15 May 2016

A Horror Movie Review: DAUGHTER OF DR. JEKYLL (1957).

Posted by Steve under Horror movies , Reviews[17] Comments

DAUGHTER OF DR. JEKYLL. Allied Artists, 1957. John Agar, Gloria Talbott, Arthur Shields, John Dierkes, Mollie McCard, Martha Wentworth. Director: Edgar G. Ullmer.

With a title like this, you can probably figure out a fully-formed plot synopsis of your own and have it come out awfully close to the one that powers this one along. Gloria Talbott plays the daughter of you know who, which I’m sure you’ve already guessed from the cast listing, but now as a orphan she goes by the name of Janet Smith. What she does not know is that on her 21st birthday, she will inherit a large estate.

Her guardian is a gentleman named Dr. Lomas, and as she and her fiancé (John Agar) visit him together in her family mansion, he finds himself duty-bound to tell her in private about her father. Strange events — murderous events — begin to happen the same evening. Can she have inherited her doomed father’s fate of turning into a werewolf at the time of the full moon?

Well, not a lot of this makes much sense, and maybe the plot you might have put together yourself would have made a better film along these same lines than this one. But as the director, Edgar G. Ulmer manages to keep the action extra spooky, especially indoors, with all kinds of innovative camera angles and an excellent use of black and white lighting. Less effective is the mist effect used in outdoor scenes, which comes off only as if you’re looking through a smeared-up lens.

One other big plus is that Gloria Talbott never looked lovelier than she does in this movie, made the same year as The Cyclops, reviewed here. This one’s ten times better, if not more, and if you’re so inclined, which I assume you are, having read this far, the movie is well worth searching out for.

Sat 14 May 2016

A Mystery Review by Barry Gardner: MATT & BONNIE TAYLOR – Neon Dancers.

Posted by Steve under Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Characters , Reviews[4] Comments

MATT & BONNIE TAYLOR – Neon Dancers. Palmer Kingston #2. Walker, hardcover, 1991. No paperback edition.

This is the second in a series set in an unnamed Florida city featuring two reporters: Palmer Kingston and his lover and rival, A. J. Egan.

Kingston is something of an eccentric, living in a garish mansion surrounded by neon signs and antique cars. Egan is a tenant in the mansion. If it all sounds a little strange, well, it is. The story, though, is a relatively straightforward tale of hijinks with the zoning board, a U. S. Attorney out to make a name for himself, and various parties trying to either aid or thwart his and the zoning board’s designs.

The attorney turns up dead, and Kingston has problems with A. J., his publisher, the law, and just about everybody else. I found him to be a very likeable character, the milieu an interesting one, and the Taylors’ storytelling skills more than adequate.

In short, I liked it, and will hunt up the first in the series. Recommended.

— The Palmer Kingston & A. J. Egan series:

Neon Flamingo. Dodd Mead, 1987.

Black Dutch. Walker, April 1991.

Neon Dancers. Walker, November 1991.

Sat 14 May 2016

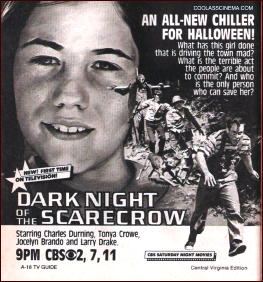

A Horror Movie Review by Jonathan Lewis: DARK NIGHT OF THE SCARECROW (1981).

Posted by Steve under Horror movies , Reviews[5] Comments

DARK NIGHT OF THE SCARECROW. Made-for-TV movie, CBS, 24 October 1981. Charles Durning, Robert F. Lyons, Claude Earl Jones, Lane Smith, Tonya Crowe, Larry Drake, Jocelyn Brando. Director: Frank De Felitta.

As an adult, returning to a horror film that scared the living daylights of me as a kid is always a fascinating experience. Before the film even begins, I am asking myself whether it’s going to be as terrifying, vivid, or scary as I remember it being. Is it going to look just plain silly, forcing me to doubt my youthful aesthetic judgment? After all, some kids just know when a movie stinks and when it’s good, right?

Enter the scarecrow. Dark Night of the Scarecrow, to be exact. As a made-for-TV movie originally aired on CBS, the movie has no particular right to be that good, let alone that memorable. As it turns out, I remembered a lot of it pretty well. Not so much the minor details, but the general atmosphere of suspense and the visceral nature of the revenge-driven plot. It’s a very unsettling movie, both emotionally and visually.

Then there’s Bubba. Portrayed by the late Larry Drake (L. A. Law, Darkman), Bubba Ritter is a kind, mentally challenged 36 year-old living with his mother on the outskirts of a small rural town. Drake’s performance is, in a word, unforgettable. He is able to convey his character’s childlike innocence, love for his mother, and his fear of the cruelty that surrounds him.

Case in point: the local men inhabiting this festering hole of bigotry are pieces of work. In particular, there is the morally repugnant Otis P. Hazelrigg (an exceptionally well cast Charles Durning), a loathsome bitter man who hates Bubba and loathes his friendship with Marylee Williams, a local girl (Tonya Crowe). When it looks as if Bubba may have been responsible for the girl’s murder, Hazelrigg and three other men exact vigilante justice on the terrified Bubba, shooting him dead in cold blood trembling for his life in a cornfield.

After the men are acquitted, things begin to get downright strange in the town. A mysterious scarecrow starts appearing, haunting the guilty consciences of the men responsible for Bubba’s death. Is it a supernatural occurrence or a prank designed into frightening the men into confessing their crime? After all, Bubba’s mother vowed that that there are other forms of justice than that dished out in courthouses. The violent deaths meted out to largely unsympathetic Bubba’s executioners in Dark Night of the Scarecrow demonstrate just how right she was.