Odessey and Oracle (1968) is the second studio album released by the British rock band The Zombies. At one time it was ranked number 100 on Rolling Stone‘s list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time:

December 2016

Fri 23 Dec 2016

Music I’m Listening To: THE ZOMBIES – Odessey And Oracle [Complete Album].

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening ToNo Comments

Thu 22 Dec 2016

EARL EMERSON РCatfish Caf̩. Ballantine, hardcover, August 1998; paperback reprint, September 1999.

This is number eleven in a series of what is so far fourteen books chronicling the cases of Seattle-based PI Thomas Black. The most recent is Two Miles of Darkness from 2015. It’s a good series. I read the first three when they first came out, but I regret to say I’ve been rather hit-and-miss with them from that point on.

In Catfish Café Emerson does something I think is rather daring. The case that he takes on is that of finding the daughter of his former partner on the police force; she’s gone missing after leaving the scene of an automobile accident, leaving the body of a dead man behind.

What is something out of the ordinary about this is that Luther Little, the girl’s father, is black, and in order to solve the case, Black has to maneuver his way through all kinds of secrets accumulated over the years by Luther’s very extended family. Not the kind of job a PI likes to do in general, but Black is white, and it takes a special knack on his part to make any kind of headway into prying the secrets loose.

There are wives and former lovers, daughters, sons and stepsons, fathers, uncles and cousins, a spunky grandmother, boy friends and more. The family is not poor, but neither are they well off. Many of them have problems. Some have prison records; the daughter Black is looking for has had a life on the streets.

To his credit, Emerson describes this family in detail well enough to convince me. The book is a long one, so it does seem to sag a little in the middle, but it’s also a complicated and interesting one. The ending also manages to gather up all the loose ends in satisfactory fashion, if not entirely happily to all of the various members of Luther’s family.

Thu 22 Dec 2016

A Movie Review by Jonathan Lewis: I ESCAPED FROM THE GESTAPO (1943).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Suspense & espionage films[5] Comments

I ESCAPED FROM THE GESTAPO. Monogram Pictures, 1943. Dean Jagger, John Carradine, Mary Brian, Bill Henry, Sidney Blackmer, Ian Keith. Director: Harold Young.

Talk about great casting. I Escaped from the Gestapo stars Dean Jagger as Torgut Lane, an escaped convict forced to work against his will as a counterfeiter for a Nazi spy ring and John Carradine as “Martin,†a Nazi saboteur and the head of the aforementioned spy ring. Both men portray their characters to the hilt in this offbeat, occasionally thematically quite dark, World War II era thriller, one that cinematically looks something like a cross between an action-packed film serial and an early film noir.

With a running time of seventy-five minutes, this programmer provides a surprising degree of characterization for noted forger Torgut Lane, demonstrating that during wartime even criminals can remain fierce American patriots. After Lane receives assistance in breaking out of prison, he soon comes to learn that his newfound friends aren’t friends at all. Rather, they are Nazi saboteurs based in Los Angeles who have decided they’ll hold Lane in virtual slavery while he works to produce counterfeit bank notes for them. Lane may be a criminal. But he’s no Nazi! And from the very beginning of his newfound captivity, he begins looking for ways to undermine the sinister Nazi plan against democracy.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention how perfectly suited John Carradine is to the role of the mysterious “Martin,†the Nazi ringleader. Urbane and polished on the surface, Martin’s deep down a true cold-hearted brute. In one particularly galling scene – one which likely shocked respectable audiences at the time – Martin sits and reads a book while his henchman beats Torgut Lane with a rubber hose. It’s a scene that would have fit well in the context of a late 1940s film noir, but seems unusually violent for a film released in 1943.

It’s also worth mentioning that the film also contains a rather unique subplot involving a Gestapo agent tasked with guarding Lane. The man named Gordon (Bill Henry) never smiles and has a killer’s look in his eyes. This leads Lane, who is clearly adept at reading people, to nickname Gordon “The Butcher.†As it turns out, Lane’s instincts are spot on. The man guarding him has a brutal past and is guilt-ridden from the atrocities in which he has participated against European Jewry while he was still in Europe. Lane is able to exploit this guilt to his own benefit. It’s a plot element that further solidifies my opinion that I Escaped from the Gestapo is far from a forgettable morale booster during wartime and is well worth a look.

Wed 21 Dec 2016

An Archived Christmas Mystery Review: ROBERT NORDEN – Death Beneath the Christmas Tree.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[4] Comments

ROBERT NORDAN – Death Beneath the Christmas Tree. Fawcett Gold Medal, paperback original; 1st printing, December 1991.

This is the second mystery adventure featuring widowed Mavis Lashley and her police photographer nephew Dale, both lovers of murder mysteries — the first being All Dressed Up to Die — and because Mavis turns out to be a very interesting woman, the story itself does, too, somewhat in spite of itself.

This one begins with a woman in a church choir being shot to death while part of a huge, glorious Christmas pageant in her church. Unfortunately several of the children in Mavis’s neighborhood are witnesses to the crime (as shepherds waiting for their cue to go on stage). Not only that, they may even know more.

This is not a happy story, as it turns out, and justice is left hanging out to dry at the end — more than which I cannot say, without telling you everything. But as a detective story, the solution to the second killing, at least, is no more subtle than one of those old five-minute Ellery Queen radio mysteries, in which the Maestro states the circumstances of the crime in three minutes, takes a minute for a commercial, then comes back in the final minute and tells you exactly how he knew who did it.

And Nordan’s prose while capable enough, is largely unimaginative — with confessions of various secrets coming forth like torrents, pages on end — but he does capture one idea very well: that while we may ever so much long for the past, what has past us by is gone and is not retrievable, whether it be our children, our youth, our cities, or (in some more general way) our way of life.

We can mourn it, whatever it is that we’ve lost, but we can’t bring it back. This book looks back, however, more than any other mystery I’ve ever read, not in anger, but in sorrow.

Bibliographic Note: There were two more in this series, Death on Wheels (1993) and Dead and Breakfast (2003).

Wed 21 Dec 2016

A Made for Cable TV Movie Review: THE PARK IS MINE (1985).

Posted by Steve under Action Adventure movies , Reviews[5] Comments

THE PARK IS MINE. Made for TV: HBO, 1985. Tommy Lee Jones, Helen Shaver, Yaphet Kotto, Lawrence Dane, Peter Dvorsky, Gale Garnett. Based on the novel by Stephen Peters. Original music by Tangerine Dream. Director: Steven Hilliard Stern.

Perhaps of some note as being the first movie made for HBO, this is a movie also made for its time, but one that has had such a cult following over the years that it has recently had a recent release on DVD (December 13th). Not many made-for-TV movies make the grade, not with official releases, they don’t.

Most of what makes the movie worth watching today is the performance of Tommy Lee Jones, no surprise there. He plays a Vietnam War veteran who is still having difficulty adjusting to civilian life. He cannot keep a job, he is separated from his wife, who won’t let him see his young boy, and most of all, he is totally burned up by the fact that no one cares for what sacrifices any of his fellow soldiers made during the war.

So what does he do? Thanks to another vet who has just committed suicide but before that secretly mined Central Park and fortified it with all kinds of heavy ammunition, he takes over the park, literally. A one man operation that keeps the police and, most particularly, the city administration, at bay. A three day period before Veterans’ Day that the park is his, that’s all he wants. No hostages, no ransom, just three days of respect.

Causes like this, especially with plenty of gunfire and bombs going off, make for movies that attract attention. Luckily no one is killed — only minor injuries — until the deputy mayor left in charge escalates matters too far, as well as over the top, when he sends in a couple of ex-mercenaries, one a former Viet Cong, with orders to kill.

This is an act that ends in disaster, and it changes what could have been a minor league protest into one of over the top comic book proportions. Helen Shaver, who is very easy on the eyes, provides more than capable support as a TV news photographer whose quest for a story lands her right in the middle of it.

There is an obvious moral to stories like this, and if done well, they can sweep the viewer along with them. This one isn’t likely to escape its cult-only status, however. The story, while it hints at more, just isn’t up to it.

Audio Bonus: Here’s the complete soundtrack recording, very effectively done by the group Tangerine Dream:

Wed 21 Dec 2016

Music I’m Listening To: LINN COUNTY “Black Night” + “Boogie Chillun.”

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening ToNo Comments

Two songs from this San Francisco-based blues rock band’s third and final album, Till The Break Of Dawn, released in 1970:

Tue 20 Dec 2016

A Book! Movie!! Review by Dan Stumpf: RAYMOND CHANDLER – The Long Goodbye / Film (1973).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[12] Comments

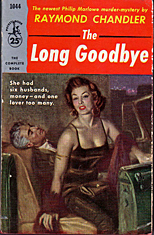

RAYMOND CHANDLER – The Long Goodbye. Houghton Mifflin, hardcover, 1954. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and soft, including Pocket 1044, 1955.

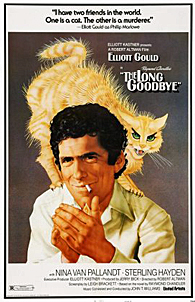

THE LONG GOODBYE. United Artists, 1973. Elliott Gould, Nina van Pallandt, Sterling Hayden, Mark Rydell, Henry Gibson, David Arkin, Jim Bouton. Screenplay by Leigh Brackett, based on the novel by Raymond Chandler. Director: Robert Altman.

I discovered Raymond Chandler back in High School, re-read him after College, and still dip into his work now and again. But I’ve kind of resisted re-visiting The Long Goodbye, which I recalled as somewhat flabby and overrated. Well, I approached it again a few years ago with interest and a bit of trepidation, wondering if I’d finish it. Then in the first couple pages I came across the line “She gave him a look that should have stuck out his back four inches,” and my ticket was stamped for the ride.

I wouldn’t call Goodbye flabby; it is/was over-rated by critics impressed by Chandler’s carping John-D-MacDonald-style about the society we live in, the sorry state of television and gays in the art world — all much less impressive fifty-odd years later. Goodbye lacks the vigor of The Big Sleep, and it’s not as poignant as The High Window, but Chandler keeps it moving with his own often-imitated prose and lively characters like Big Willie Magoon and Mendy Menendez, a flamboyant gangster who gives the piece a sense of motion even when there’s not much going on. I have to say, though, Goodbye really needs these colorful touches, because this plot re-e-ally takes its time unspooling. In all, I’m glad I took another look at it, but it’s far from his best.

In 1973 Robert Altman and Leigh Brackett (who co-adapted The Big Sleep for the movies in ’45) made a movie of The Long Goodbye which was generally scorned by critics, savaged by Chandler fans and ignored by the public — I’ve always loved it.

In those days before noir came back in style, it was artistically impossible to do a hard-boiled mystery like they used to – look at the sorry attempts with James Garner and Robert Mitchum – so Altman/Brackett turned “Raymond Chandler’s savagely disenchanted outlaw-within-the-law†(Bosley Crowther) or the “Knight Without Meaning†(Charles Gregory) into a faintly comic, out-of-step icon.

The sensitivity is still there, along with the Instant Bullshit Detector, but the showy hardness is replaced by bemused detachment and Popeye-mutter. It works, enacted by Elliott Gould and a superb cast including Nina Van Pallandt, Sterling Hayden, director Mark Rydell (great in the flashy-gangster role) Henry Gibson(!) and Arnold Schwarzenegger(try to spot him.)

I’m not a big fan of the late Robert Altman, but (as yet another critic pointed out) this movie shares a lot of qualities with Alphaville and Point Blank: dis-location of space and time, use of décor as landscape and landscape as décor, absurd violence, and stock characters who refuse to act like stereotypes… in all a film kinky, off-beat and surprisingly faithful.

As an interesting sidelight, Long Goodbye was done for television in 1954, or thereabouts with Dick Powell as Marlowe on an hour-long show called Climax – the same show that first did Casino Royale.

And another interesting bit: When this film came out I was dating two women, and dating them pretty seriously — seriously enough that I couldn’t afford to keep it up very long, so I took them to The Long Goodbye (on different nights; this was the 70s, not the 90s) to see how they reacted: One loved it, the other asked me how I could possibly enjoy such a film, and told me never to take her to another like it.

In due course, I married the second one.

Mon 19 Dec 2016

A Christmas Review by William F. Deeck: DAVID WILLIAM MEREDITH – The Christmas Card Murders.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Reviews[7] Comments

William F. Deeck

DAVID WILLIAM MEREDITH – The Christmas Card Murders. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1951. No paperback edition.

Four men living close together in Stelton, New Jersey, receive Christmas cards with Happy New Year struck out and an added message reading, “You will die before the old year ends.” A practical joke by a child in the neighborhood, Douglas Martin concludes. And then one of the four men is stabbed to death on Christmas Eve.

Murder and attempted murder follow as Martin, a reporter who is recovering from polio, investigates in an effort to keep himself and others alive.

Quite a Christmasy novel, with not only murder after a carol singing but chapter titles taken from Clement Clark Moore’s “A Visit From St. Nicholas.” Martin is a well-drawn character, as are his family and neighbors, with all their strengths and weaknesses. My only complaint would be that the author unnecessarily repeats the major clue, and that repetition immediately put me on to the murderer. Highly recommended.

Bio-Bibliographical Notes: David William Meredith was the pen name of Earl Schenck Miers (1910-1972). This as his only mystery novel, under either name. According to Wikipedia, Miers was “an American historian. He wrote over 100 published books, mostly about the history of the American Civil War. Some of them were intended for children, including three historic novels in the We Were There series.”

Mon 19 Dec 2016

Music I’m Listening To: LAMB – A Sign of Change [Complete Album].

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening ToNo Comments

Lamb was a San Francisco-based rock group who appeared at the famed Fillmore Auditorium several times in the early 70s. The band was formed by Texan singer Barbara Mauritz and guitarist Bob Swanson.

Says Wikipedia: “Their debut album on the Fillmore label, A Sign of Change, was perhaps their most uncompromising and experimental, relying largely on jazz-folk acoustic arrangements and spotlighting Mauritz’s impressive voice on impressionistic, dream-like lyrics.”

The album has been released on CD but is out of print. Be prepared to pay $40 and up.

Mon 19 Dec 2016

NERO BLANC – Two Down. Berkley, trade paperback original, 2000; mass market paperback; August 2001.

This is number two in a series of twelve crossword-related mysteries tackled together by Newcastle MA-based PI Rosco Polycrates and the newfound love of his life, Belle Graham, crossword editor of the Evening Crier. A big attraction for readers of the series was always the inclusion of six or so crossword puzzles that, when solved, contribute greatly to the solving of whatever case they happen to be working on at the time.

Missing in Two Down are the wife of a local and very wealthy businessman and a close actress friend trying to escape Hollywood and all that too much fame entails. They set sail together for Nantucket Island and never made it. Rosco is hired by the husband first to hurry up the Coast Guard search, then to discover what went wrong.

The overlap between readers of detective puzzle readers and crossword solvers must be sizable, but in spite of the longevity of the series, on the basis of this first sample on my part, I don’t think the two authors (Cordelia Frances Biddle and Steve Zettler) got the two ideas to mesh as well as I thought they should. The crossword puzzles themselves are very well constructed, but the whole concept of anonymous puzzles sent to Belle on the part of a person unknown for some mysterious purpose never rose beyond the totally artificial stage.

It does not help that the story is very predictable and that the characters themselves are only gossamer thin, never coming to life for me. Nor was I pleased with the act of horrific violence toward the end, a death that seems glossed over far too soon — in the very next chapter, in fact, in true cozy fashion.