From this jazz singer and five-time Grammy nominee’s album Wild for You, released in 2004. I think you’ll recognize the song, one of my favorites:

May 2017

Thu 4 May 2017

Music I’m Listening To: KARRIN ALLYSON “Help Me.”

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening ToNo Comments

Wed 3 May 2017

MIKE NEVINS on HARRY STEPHEN KEELER, GEORGES SIMENON and COLIN DEXTER.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Columns , Obituaries / Deaths Noted[4] Comments

by Francis M. Nevins

Last month I talked about some of the correspondence between Erle Stanley Gardner, creator of Perry Mason, and Harry Stephen Keeler, creator of the craziest characters — not to mention the books that housed them! — ever conjured up on land or sea. But I had no space to say anything about the one Keeler book in which ESG is mentioned. THE GALLOWS WAITS, MY LORD! was written in 1953, the year Harry’s last novel to appear in English in his lifetime came out, and was published nowhere, not even in Spain, which continued to put out books of his until shortly before his death in 1967.

Thanks to that rogue publisher Ramble House, GALLOWS has been available in Keeler’s native tongue — which is not to be confused with English! — since 2003, and it can still be found on the Web. The setting is the mythical banana republic of San do Mar and the plot has to do with the frantic attempts of a Yank who bears the un-Yankish name Kedrick Merijohn to escape hanging, by order of Presidente Doctor Don Carlos Foxardo — whose crack-brained treatise is the required text in every hospital in the country, not to mention its med school! — for the poisoning murder of a stranger while the stranger was trying to poison him. It doesn’t help Merijohn’s case that he inexplicably changed shoes with the corpse after the fatal incident.

Very late in the book we join British diplomat Sir Clyde Kenwoody in Hollywood where he meets Detective Sergeant Pete O’Swin, who’s wearing a purple derby and a rainbow-hued plaid jacket.

This paragraph, which no one else living or dead could have written, not only reveals how HSK made use of ESG — and why whenever I write about our Harry I tend to insert clauses like this one, which invariably end with an exclamation point! — but perhaps will explain to readers who have been spared any acquaintanceship with his immortal works why I call him the wackiest wackadoodle who ever wore out a typewriter ribbon.

Keeler sometimes played the wack for the game’s sake, sometimes to make a point, and occasionally he did both at once, as witness a passage one chapter later when the same O’Swin expounds on one of Harry’s loony laws while also reminding us that his creator was something of a Socialist.

When the issue is raised that perhaps the actions of O’Swin and Sir Clyde are unconstitutional, the diplomat points out that “if you’re taken over there [to the police station], and start to set forth your constitutional rights and prerogatives, you’ll only wake up a few hours later lying on a cold cement floor of an isolated cell, with an aching — more probably broken — jaw….†To which O’Swin adds: “Well … we have evoluted certain interestin’ methods t’ cope with the Bill o’ Rights and the Constitution.†This is precisely how matters stood until a number of years later when the Supreme Court began applying federal Bill of Rights protections to criminal defendants in state courts.

In another recent column I devoted an item to the strange case of Georges Simenon’s stand-alone crime novel STRANGERS IN THE HOUSE, which was published in Nazi-occupied France in 1940 as LES INCONNUS DANS LA MAISON and made into a French movie of the same name the following year but wasn’t translated into English until after World War II. The translation, by Geoffrey Sainsbury, appeared in England in 1951 and in the U.S. three years later.

It’s the same translation both times, right? Wrong!!! In the English version as reprinted in 2006 by the New York Review of Books with a new introduction by P.D. James, we find on page 70 a passage where the protagonist Hector Loursat ponders whether there are any similarities between him and any of the strangers in his house. “Yet there was no connection. Not even a resemblance. He hadn’t been poor like Emile Manu or a Jew like Luska….â€

In the American version this becomes: “There was no connection. No resemblance. He hadn’t been poor like Manu, or an Armenian like Luska….†Incidentally, Manu’s first name in the American version is Robert, not Emile. The first alteration is understandable, and exactly what Anthony Boucher had done several years before when translating for EQMM a Simenon story with a Jewish villain. But why the second change? And, if we were to compare the two versions line by line, how many more alterations would we discover?

It’s not connected with anything else in this column, but I feel compelled to bring up a recent death. Colin Dexter, creator of the immortal Inspector Morse, died on March 21, age 86. I met him once, when he was on a book tour with a St. Louis stop, and was smart enough to bring with me the only Morse novel I then had in first edition, LAST SEEN WEARING (1976), which he signed for me.

The earliest entries among his thirteen novels didn’t make much of an impression, but once the Morse TV movie series was launched, John Thaw’s superb performance as the brilliant but flawed Oxford sleuth caused Dexter’s sales to climb into the stratosphere. The series lasted for 33 episodes, each approximately two hours long. Ten of them, including my favorites — “The Silent World of Nicholas Quinn†and “Service of All the Dead†— are based on his novels.

The other three novels — THE RIDDLE OF THE THIRD MILE (1983), THE SECRET OF ANNEXE 3 (1986) and THE JEWEL THAT WAS OURS (1991) — were never officially filmed. Three early episodes were based on ideas or other material by Dexter, and when he turned them into the novels above, they were not remade. (The respective telefilm titles for the trio are “The Last Enemy,†“The Secret of Bay 5B†and “The Wolvercote Tongue.â€)

In Dexter’s final novel, THE REMORSEFUL DAY (2000), which was also the source of the last Morse TV movie, the Inspector dies — not at the hands of a murderer but because, as Dexter explained, he drank too much, smoked too much and almost never exercised. Well, he may have died physically, but I strongly suspect he and his creator will live on for many decades to come.

Wed 3 May 2017

A Science Fiction Review: CLIFFORD D. SIMAK – Shakespeare’s Planet.

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Science Fiction & Fantasy[8] Comments

CLIFFORD D. SIMAK – Shakespeare’s Planet. Berkley/Putnam, hardcover, 1976. Berkley, paperback; 1st printing, May 1977. Del Rey, paperback, 1982.

Back in my teens and 20s when I was reading SF by the armload, two of my favorites were, of course, Robert A. Heinlein and Isaac Asimov. I say “of course” because those were the two authors that my SF-reading friends were also reading (all two of them).

But as time went on and I started reading Astounding and Galaxy and some of the other magazines that came out around then, I started finding other authors that appealed to me even more than the big two. (I won’t go into who the “Big Three” might be.)

As you may have guessed by now, this is when I discovered Clifford D. Simak. He wrote simple stories about some not so simple ideas, and what’s more he made them sound simple. I grew up in a small town in the Midwest (Michigan), and Simak was if nothing else a master of small town ideas and values, and of creating characters who believed in them, no matter how far out in time or space they happened to be.

Shakespeare’s Planet is a prime example. It begins with Carter Horton waking up on an expeditionary spaceship as the only survivor of four humans on board. His only companions, if you will, being a robot named Nicodemus and a ship named Ship, controlled by the minds of three people who gave up their bodies for the voyage: a monk, a scientist and a grande dame.

The planet the ship has found is inhabited, as it turns out, by an alien creature named Carnivore. Recently deceased is a human dubbed Shakespeare from the book of plays he owned. Tunnels in space have led to this world, but something has gone awry, as they function only in one direction: in, not out.

And the ship cannot return to Earth, which is now 1000 years away. One new arrival to the planet after Horton is Elayne, a female explorer of the tunnels through space. She is also trapped with the others. But there are other beings on the planet, each more fantastic than the next, nor do they get along as well as those already described.

Before the book ends there is a lot of discussion of life, the universe, and the role of humanity in it. Some of this discussion may be dismissed by some as being on the level of sophomores living in a college dormitory, but Simak has a way of making it seem a whole lot more than that — he works with a canvas the size of the entire cosmos –and if I could explain what he does any better than that, I’d be writing SF instead of only reading it.

Tue 2 May 2017

A Western Book! Movie!! Review by Dan Stumpf: LES SAVAGE JR. – Return to Warbow / 1958.

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Western Fiction , Western movies[3] Comments

LES SAVAGE, JR. – Return to Warbow. Dell First Edition #65, paperback original; 1st printing, 1955.

RETURN TO WARBOW . Columbia, 1958. Philip Carey, Catherine McLeod, Andrew Duggan, William Leslie, Robert Wilke, James Griffith and Jay Silverheels. Written by Les Savage Jr from his novel. Directed by Ray Nazzaro.

I was mildly impressed by Les Savage’s novel for the efforts it took to be a bit different; the film he wrote from it impressed me too, but for all the wrong reasons.

To start with the novel — well actually, before the novel starts, a small-time rancher named Elliot Hollister needed money for his sick wife, but he was already deep in debt and the only friends he had in the town of Warbow were the drifters and low-lifes he met in saloons where he drank to drown his troubles.

One of these reprobates roped him in on a stagecoach heist, but a third party horned in, killed Elliot’s partner and a popular local businessman and left Elliot holding the bag — but not the loot. So as the story starts, Elliot has served his time and returns to Warbow, where he is universally reviled and suspected of having stashed the haul, and he means to figure out who the killer really was.

Got all that? Well pay it no mind, because the central character here is Clay Hollister, Elliot’s adult son who has grown up, got out from under the onus of his father, built up the ranch, and bids fair to marry the daughter of the man his daddy is thought to have killed. When his father hits town Clay feels compelled to take him in and the two begin an uneasy relationship punctuated by violent encounters with the locals who still hate Elliot for that killing he never done, plus those who think he can lead them to a fortune in stolen gold, and the mysterious third man, who simply wants him silenced in the surest way possible.

Savage gives the thing a bit of emotional complexity, particularly as some of Elliot’s persecutors see the results of their work and waver a bit, and he sets the tale in the nasty midst of a Montana blizzard, lending a welcome edge of realism. None of this makes Warbow a great novel, but it does lift it a bit out of the ordinary.

You can imagine my surprise then, when I watched the film version, also written by Les Savage Jr., and found he had leeched out just about everything that made the book worthwhile.

The film eschews the wintry setting of the book in favor of that perpetual sunny summertime of just about every other Western ever made. And in this version there’s no Elliot; Clay Hollister (Phil Carey) is an unrepentant robber who breaks from a chain gang with a couple of other bad guys and returns to his home town to recover the loot he left with his weakling brother (a fine performance from James Griffith).

There are the usual complications: Hollister’s new partners want more than their share of the loot (a wrinkle that recalls Big House U.S.A., reviewed here not long ago) his ex-girlfriend has married upstanding Andre Duggan, and they are raising his son as their own; there’s a posse on his trail; and that brother of his is awfully evasive about where he hid the dough.

Which is pretty much where things just stop and pot around for awhile. Everyone chases everyone else around the Columbia Western Town set and the familiar environs of Simi Valley. We get a few fights, a bit of shooting, and no real sense that anything’s going anyplace very much. Ray Nazarro was always a competent director, but that’s all he was, and he never enlivens the rather stale proceedings.

As for the script, well I have never seen an author trash his own work so completely, and I just hope Savage got well paid for it.

Tue 2 May 2017

Archived Review: SIMON NASH – Dead Woman’s Ditch.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Reviews[3] Comments

SIMON NASH – Dead Woman’s Ditch. Geoffrey Bles, UK, hardcover, 1964. Roy, US, hardcover, 1966. Perennial Library PL777, US, paperback; 1st printing, 1985.

Most of this adventure of Adam Ludlow takes place in and around a small English hotel in remote Somerset at the end of September, and for some reason, all of the rooms are filled. What it takes a while for the police to realize, after one of the guests has been murdered, and unpleasant man by the name of Silas Taker, is that each of the others has a motive, that of blackmail.

Scotland Yard is called in, and back in the days when they could still so things ike that, they call upon Ludlow for assistance themselves. Ludlow is what you might call a literary academician, an amateur dabbling in crime, and in this one he gets a (brief) taste of impending personal violence as well.

There are obviously lots of suspects in the case, plus lots of clues and false trails, and it’s still a puzzle to me why the naming of the killer seems to fall as flat as it does. Barzun and Taylor [in A Catalogue of Crime] feel that this is one of Ludlow’s weaker adventures. Since it’s the first I’ve ever read, I wouldn’t know, but while I enjoyed the book, I guess what I was expecting was a stronger finale.

Bio-Bibliographic Notes: Simon Nash was the pseudonym of Raymond Chapman, 1924-2013, a Professor of English at London University and an Anglican priest. There are no books in Hubin under his own name.

The Adam Ludlow series [each also features Inspector Montero] —

Dead of a Counterplot, 1962.

Killed by Scandal, 1962.

Death Over Deep Water. 1963.

Dead Woman’s Ditch, 1964.

Unhallowed Murder, 1966

Tue 2 May 2017

Music I’m Listening To: RUBY STARR – Scene Stealer (Complete Album).

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening To[2] Comments

Ruby Starr was the long-time lead singer for the Southern rock band Black Oak Arkansas. This solo album is from 1976.

Mon 1 May 2017

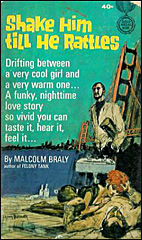

A 1001 Midnights Review: MALCOLM BRALY – Shake Him Till He Rattles.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Reviews[6] Comments

by Ed Gorman

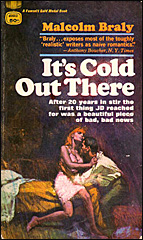

MALCOLM BRALY – Shake Him Till He Rattles. Gold Medal k1311, paperback original; 1st printing, 1963. Pocket, paperback, 1976. Stark House Press, trade paperback 2006 (a two-in-one edition with It’s Cold Out There).

When On the Yard, the novel Malcolm Braly based on his ears in prison, appeared in 1967, everyone said he was major. But for a major writer, Braly, who was killed in an automobile accident at age fifty-five, is virtually forgotten today.

By any standard, however, Yard and the three novels he wrote for Gold Medal in the early Sixties are books worth reading, books in many respects as frenetic and confessional ional as the more literary novels of the era.

Shake Him Till He Rattles concerns Lee Cabiness, a sax player whose only goal is to stay out of prison. Lieutenant Carver of the San Francisco narc squad has other ideas. Braly obviously based Carver on both personal experience and his reading of Dostoevski, for the cop here is almost mythic in his malice and darkness, his repudiation of all human values.

Braly posits the jazz musicians of his book, however, as magic revelers in the human song: “Furg was a child, a vagabond child, a fey and travel-torn minstrel barely suffered in the halls of the minor barons. But, whether they knew it or not, Furg was necessary to them, to breathe into their lives the vital stuff of myth.”

Later Braly describes the same world Jack Kerouac earlier set down as “beat.” Only Braly saw it differently: “People were coming in. Pink, clean examples of college and social Bohemia, mostly young, roughly thirty per cent gay. He saw Clair moving around. In her white dress with her pale hair she looked chilly. He caught her smile coming and going, like distant sunlight on ice.”

The conflict between Cabiness and Carver grows, of course, as the narc makes frustrated moves on his prey, trying to demean and unman him as he closes in. The battle, again, is out of Dostoevski — the perversion of a legal system and its victim. The details, interestingly, remain “beat.”

Braly’s fiction testifies to the indomitable human spirit of the intelligent loser. There is a wealth of sadness and humor alike in his pages and a kind of quirky defiance. His was the ultimate loneliness, it seemed, belonging as he did to neither world, criminal nor straight. He charted a type of experience seldom seen in crime fiction –the real world of the criminal.

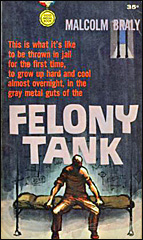

A rediscovery of this and Braly’s other fine novels — Felony Tank (1961), It’s Cold Out There (1966), and The Protector (1979) — is long past due.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

UPDATE: The good news is that of the books Ed Gorman mentioned in this review, I believe that all but The Protector is currently in print. Stark House Press has reprinted this, It’s Cold Out There and in a separate edition, Felony Tank, while The New York Review of Books has recently published On the Yard.