Another song I challenge you to listen to and sit absolutely still:

June 2018

Fri 15 Jun 2018

Music I’m Listening To: DELBERT McCLINTON “Why Me?”

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening To[2] Comments

Thu 14 Jun 2018

Reviewed by LJ Roberts: JOHN LESCROART – Poison.

Posted by Steve under Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Characters , Reviews[4] Comments

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

JOHN LESCROART – Poison. Dismas Hardy #17. Atria Books, hardcover, February 2018.

First Sentence: If opening day wasn’t the happiest landmark in Dismas Hardy’s year, he didn’t know what was.

San Francsico attorney Dismas Hardy is recovering from two gunshot wounds and thinking about retirement. The murder of Grant Wagner, the owner of a successful family business, changes his plans. Abby Jarvis was a former client of Hardy’s and is the prime suspect. She was Wagner’s bookkeeper and was receiving substantial sums of cash off the books, but she claims she is innocent. The further Dismas digs into the family relationships, the more precarious his own life becomes.

If you’ve not read Lescroart in a while, or ever, this is a good time to change that. He is a true storyteller. He engages the reader from the beginning with his style and humor— “Part of it, of course, was AT&T Park, which to his mind was essentially the platonic ideal of a ballpark. (Although, of course, how could Plato have known?)â€

There is a fair number of characters in the story, but Lescroart is adept at introducing them all and making them distinct enough not to become confused. Having the perspective of the victim’s family is an interesting approach.

In addition to a good recounting of the past case which caused Hardy to be shot, there is an excellent explanation of the steps and process of the law. Rather than its being dry reading, it involves one as if they are the defendant. Early on, it is revealed that poison was the cause of Wagner’s death, and interesting information on wolfsbane is provided. The link made from the first murder to the second is nicely done as it then becomes personally dangerous to Dismas.

The mention of food and family— “Hardy made them both an enormous omelet in his black cast-iron pan… They discussed the irony that he’d spiked the eggs with a cheese from Cowgirl Creamery named Mt. Tam, and that Frannie was going out to climb the very same Mount Tamalpais with her women’s hiking group in the next half hour or so.†—local landmarks, and all the San Francisco references, add realism to the story. Another such touch is the mention of a fellow author— “…C.J. Box novel, stopping on a high note when he laughed aloud after coming across the line ‘Nothing spells trouble like two drunk cowboys with a rocket launcher.’â€

Lescroart not only shows what happens on the defense side of a case, but also with the homicide team and, somewhat, with the prosecution team. The crisis within the Hardy household is realistically portrayed. Lescroart has a very good way of subtly increasing the suspense.

Poison is an extremely well-done legal thriller filled with details which can seem overwhelming yet are interesting and, most of all, important. The well-done plot twists keep one involved and the end makes one think.

The Dismas Hardy series —

1. Dead Irish (1989)

2. The Vig (1990)

3. Hard Evidence (1993)

4. The 13th Juror (1994)

5. The Mercy Rule (1998)

6. Nothing But the Truth (1999)

7. The Hearing (2000)

8. The Oath (2002)

9. The First Law (2003)

10. The Second Chair (2004)

11. The Motive (2004)

12. Betrayal (2008)

13. A Plague of Secrets (2009)

14. The Ophelia Cut (2013)

15. The Keeper (2014)

16. The Fall (2015)

17. Poison (2018)

18. The Rule of Law (2019)

Thu 14 Jun 2018

ED McBAIN – Another Part of the City. Mysterious Press, hardcover, 1986; paperback, April 1987.

I wonder if this was ever intended to be the first of a new series for McBain, or if it was never meant to be more than the one-shot it is. All of his 87th Precinct stories take place in Isola, a purely fictional borough of a larger unnamed city. As a change of pace, perhaps, Another Part of the City, still a police procedural in the same vein as the other series, definitely takes place in Manhattan.

The primary detective in this one is a homicide detective by the name of Bryan Reardon. He has a partner and fellow officers, but all of the others seem to disappear ito the cold December air, except when they show up every so often in the underheated squad room on their own cases and pieces of his, as needed.

Which leaves Reardon pretty much on his own to tackle the case of the shooting of a Italian restaurant owner in his precinct’s part of town — all the way downtown. Tied in somehow, as McBain relates the tale, are the various members of an uptown family — part of the rich and powerful elite of the city — as they busily try to accumulate millions of dollars in ready money to help seed a billion dollar project they have in mind — and one they strongly prefer to keep a secret.

And what connection does Reardon’s case have to do with them? Quite a bit, of course. This is the kind of story in which the twain definitely do meet. We’d be more surprised if they didn’t.

Quite a bit of Reardon’s private life is revealed to us as well. He is going through a divorce, unwanted on his part, with the custody of his six-year-old daughter at stake. A bit of romance with a female member of a jury which allowed the defendant got free — a rapist who Reardon helped haul in — seems unlikely when it begins, but by book’s end, things seem to be moving along quite well in that regard.

McBain/Evan Hunter is such a good writer that it’s easy to miss how slim and trim the book is, under 200 pages long, but that’s no complaint as far as I’m concerned. I was bothered quite a bit more by the fact that Reardon resorts to reading old newspaper accounts of the murder of the man whose death connects Story A with Story B. I don’t know why he didn’t get in touch with the officers in charge of the case. I think it would be to be a lot more effective way to go about it.

[WARNING: PLOT ALERT] But in the end, he has untangled all of the various plot strands, and he knows who done it and why. But can he prove it? In true noirish style, that is the question. (And hence the title of the book.)

Wed 13 Jun 2018

A Western Double Bill Reviewed by Dan Stumpf: THE FASTEST MAN ALIVE (1956) / FIVE GUNS TO TOMBSTONE (1960).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Western movies[9] Comments

THE FASTEST GUN ALIVE. MGM, 1956. Glenn Ford, Jeanne Crain, Broderick Crawford, Russ Tamblyn, Leif Erickson, John Dehner, Noah Beery Jr. Written by Frank D. Gilroy and Russell Rouse from an original teleplay (The Last Notch, 1954) by Gilroy. Directed by Russell Rouse.

FIVE GUNS TO TOMBSTONE. United Artists, 1960. James Brown, John Wilder, Walter Coy, Robert Karnes, Della Sharman, Willis Bouchey. Written by Richard Schayer and Jack DeWitt, from an original screenplay (Gun Belt, 1953) by Arthur E. Orloff.

Two films I happened to watch back-to-back, and they go me to thinking….

The Fastest Gun Alive was based on an early television drama, and it has the pared-down self-importance of that time. Where Shane mythologized the clichés of the Western, this seeks to codify them, with Glenn Ford as the eponymous pistolero, trying to resist his addiction to firearms until called on to save his community.

According to the story, if anyone is known as a fast gun, every other gunfighter in the known universe will come after him, and they will meet on Main Street with guns holstered for a fair fight. Pure bosh of course, conveyed with a great deal of talk, but MGM saw fit to stretch the thing out by ringing in Russ Tamblyn for an acrobatic and completely extraneous dance number. There’s also the usual nod to High Noon, with the townsmen cowering for safety (and more talk) in a church as they hide from fast-gun Broderick Crawford and his back-up group.

On the plus side, Director Russell Rouse opens it out well, Glenn Ford delivers a fine performance, and there are a lot of familiar B-Western faces around. Best of all, there’s John Dehner in a very well-written part as Brod’s lieutenant owl-hoot. This, with Man of the West, puts Dehner at the top of my list as Best of the 2nd-String Bad Guys.

Five Guns to Tombstone, on the other hand, boasts no self-importance at all, and the players will be familiar only to the most devoted of B-Western fans. Directed by that veteran hack Edward L. Cahn (The She Creature, It: The Terror from Beyond Space) it moves with an uncomplicated simplicity that celebrates, rather than solidifies, the familiar paces of its story.

The story? Ah yes. Something about another ex-gunfighter (James Brown) trying to get along peaceable-like until his outlaw brother drags him into a Wells Fargo robbery fraught with treachery and sudden endings. No memorable acting here, but everyone is more than competent, and the parts only require as much depth as a strip of celluloid – that and the ability to ride, fight and shoot convincingly. And speaking of shooting: In this movie, everybody, good guys and bad, pull out their irons at the first sign of trouble and go in shooting.

Five Guns is hardly memorable, but as I watched it zip through its allotted time, after listening to Fastest Gun talk its way along, it was like a breath of fresh and simple Western air. Not a great western, maybe not even a very good one, but I found it refreshing.

Mon 11 Jun 2018

THE NON-MAIGRET NOVELS OF GEORGES SIMENON, by Walker Martin.

Posted by Steve under Authors[21] Comments

by Walker Martin

In the comments following Steve Lewis’s review of Georges Simenon’s Inspector Maigret novel, The Bar on the Seine, he asked about my favorite non-Maigret novels. I see from my notes that I spent most of 2015 reading Simenon’s psychological crime novels. I read most of the hundred or so novels and even thought of writing an article for Mystery*File about my experience. But I couldn’t figure out how to discuss 75 or so novels in an article without making it into a long book.

But now that the question has come up again, here’s a short answer. For anyone interested in Simenon’s non-series crime novels, I recommend that you buy an omnibus of four novels titled A Simenon Omnibus (Hamish Hamilton, UK, 1965). Here are my notes on all four:

MR. HIRE’S ENGAGEMENT. This was one of the first of his serious non-Maigret novels. Told from the viewpoint of a very strange man, a peeping Tom. Made into two movies: Panique (1947, France) and Mr Hire (1989, France).

SUNDAY. Told from the viewpoint of a guy plotting to poison his wife. Looks autobiographical to me especially in regard to his relationship with the girlfriends. Simenon said more than once that he had thousands of sexual encounters.

THE LITTLE MAN FROM ARCHANGEL. Excellent tale of a second hand book store owner and stamp collector who makes the mistake of marrying a slut 16 years younger. He’s 40 and she is 24. Needless to say, this does not have a happy ending. The book and stamp details are fascinating.

THE PREMIER. Also known as The President. Not only a study of politics and the political life but also a look at old age and the impact it has not only on the famous but also every man. I was so impressed by this novel that I reread most of it immediately. Made into a 1961 movie starring Jean Gabin (Le President).

I consider all these novels excellent and there are many more titles that impressed me, too many to list here.

Sun 10 Jun 2018

A Western Movie Review by Jonathan Lewis: THE TEXICAN (1966).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Western movies[10] Comments

THE TEXICAN. Columbia Pictures, 1966. Audie Murphy, Broderick Crawford, Diana Lorys, Luz Márquez, Aldo Sambrel, Anthony Casas, Gerard Tichy. Director: Lesley Selander.

I feel as though I liked The Texican far more than I deserved to. Perhaps that’s a strange way to begin a film review, but it seems apt in this case, mainly because, all things considered, this Audie Murphy vehicle has a lot of noticeable flaws. First of all, there’s the score, which fits perfectly in a quirky late 1960s paella Western but which completely overwhelms this movie and feels gratuitously out of place. Then, there’s the dubbing of voices. And not just the Spanish actors, but also that of Broderick Crawford, whose voice was likely dubbed into Spanish and then back into English. Much like the film soundtrack, it seemed out of place.

What won me over, I confess, was seeing Murphy in a Western role that was far less squeaky-clean than many of the programmers he starred in throughout the 1950s. Not that he always played perfect heroes in the past. But in The Texican, it also seemed as if being physically out of Hollywood and no longer on a studio lot allowed Murphy to portray a world-weary gunfighter in a more convincing manner than he could have when he began his acting career. Sadly, Murphy would pass away five years later in a tragic plane crash in Virginia.

There’s also Broderick Crawford, whom I mentioned above, who is a superbly intimidating physical presence, even without his trademark growly voice. He portrays a heavy (pun semi-intended) by the name of Luke Starr who has the town of Rimrock under his thumb. That is until Jess Carlin (Murphy) begins to investigate the mysterious death of his brother Roy, a newspaperman who was a thorn in Starr’s side.

The plot, for a 1960s Western, is rather conventional, but sometimes it’s good to revisit traditional narratives. Not every movie has to deconstruct the Western mythos. From what I have ascertained online, The Texican is a reimagining of Lesley Selander’s 1948 film Panhandle, also co-written by John C. Champion, in which Rod Cameron took top billing. I haven’t seen that one, but it’s now on my list.

As far as The Texican goes, your cinematic life won’t be lacking if you never end up catching up with it But for simple escapist entertainment that checks all the boxes, you could do a lot worse.

Sun 10 Jun 2018

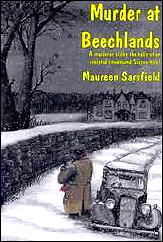

MAUREEN SARSFIELD – Murder at Beechlands. The Rue Morgue Press; trade paperback; 2003. Originally published in the UK as Dinner for None, Nicholson & Watson, 1948. First published in the US as A Party for Lawty, Coward-McCann, 1948.

I wonder how many of you have ever heard of Maureen Sarsfield before starting to read this review? Not many, I don’t imagine, and yet, on the basis of my reading this one just now, perhaps you should have.

Not much is known of the author. She wrote two mysteries and one mainstream novel, Gloriana, the latter never published in the US and good luck on finding a copy. For the sake of completeness, her other mystery is:

Both mysteries feature the same detective, Inspector Lane Perry, but I’m getting ahead of myself. When the folks at Rue Morgue Press, Tom and Enid Schantz, publish a book, their introductions always provide in-depth looks not only at the book itself but also at the author, chatty and informative. Maureen Sarsfield has them stumped, this time. The lady seems to have disappeared without a trace, leaving behind her all sorts of questions, such as, why only the two detective novels and no more?

Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV happens to have a piece of data the Schantzes don’t include in their introduction to Murder at Beechlands, and that is that the author’s real name was Maureen Pretyman. (On the Rue Morgue website, I see, however, that they do mention that she wrote children’s books under that name, so it isn’t something they don’t know.)

One of the ways of coming up with a detective novel is to reinvigorate the well-used idea of the isolated mansion house where murder has occurred, with any one of the people in the house capable of being the guilty party. Beechlands is such a mansion, sort of. What it is really isa drab but dowdy hotel in Sussex, and the blizzard that snows in all of the guests (some paying, some not), staff and servants is the same storm that forces Inspector Parry’s car off the road, just in time to have him witness the discovery of a body during an outdoor snowball party.

Soon enough the phone lines are cut, reducing drastically the chances that the dead man either fell or jumped out of the window on his own, but the burglar alarms are left on, making sure that no one can escape without being noticed. Every so often a recap (of who may have done what to whom, and who was where when) is offered, which was not a bad idea on the author’s part, because that is 99% of what this detective novel is about.

After a while, in fact, you may even get the idea, if this is your kind of story to begin with, that too much of a good thing is not so good after all.

But the author’s sure hand on keeping the reader’s eye away from what is essential is also a key ingredient, which is a small inside joke on my part, because as soon as the key to the hotel safe is found, all of the mystery immediately begins to unravel. The characters themselves are minor beings, Lane Perry included, but some of the readers of this story may eventually find themselves becoming wistful about some of them.

The England in this story is long past, and so is the type of mystery this is. One certainly may wonder why Maureen Sarsfield never wrote more than the two detective novels she did, but on the other hand, the day for detective novels like this one was waning as soon as it was first written. If this is the kind of mystery story you like, however, you will really like this one.

NOTES: Enid Schantz died in 2011, and while I don’t know the exact date, Rue Morgue Press closed down operations shortly thereafter. The website referred to in this review is no longer active.

Bill Deeck reviewed this same book earlier on this blog. You can read his comments here.

Sat 9 Jun 2018

A Movie Review by Dan Stumpf: CASBAH (1948).

Posted by Steve under Films: Comedy/Musicals , Reviews[4] Comments

CASBAH. Universal, 1948. Tony Martin, Yvonne De Carlo, Peter Lorre, Marta Toren, Hugo Haas, Thomas Gomez. Screenplay by L. Bush-Fekete and Arnold Manoff. Directed by John Berry.

The idea of a musical remake of Algiers / Pepe le Moko starring Tony Martin and Yvonne De Carlo struck me as so incredibly kitschy that I had to see it. I went into this movie hoping for something spectacularly awful, but I was disappointed — happily so, because it’s really quite a fine film, and worthy in my opinion to stand beside its romantic forebears.

If you’re not familiar with the tale, it’s about master thief Pepe Le Moko, who rules a Thieves Kingdom in the Kasbah, but knows he will be caught if ever he tries to leave. And if you can’t see the ending coming from here, well I’ll just let it surprise you.

I will say up front that Tony Martin is the real surprise here, displaying a brooding discontent light years away from The Big Store or his other light-weight musicals. Yvonne De Carlo offers her usual exotic thing as his Algerian squeeze, and Marta Toren lends just the right touch of wistful class to her role as the woman who awakes Pepe’s nostalgic yen for Paris.

Even better are the supporting players: Thomas Gomez as a crude police chief, Herbert Rudley as Marta’s acquisitive sugar-daddy, Douglas Dick as Pepe’s old-cohort-turned-quisling, the legendary Hugo Haas, and especially Peter Lorre as the only character who moves easily among them all.

Lorre in fact, is the glue that holds the story together, in one of the best parts of his later career: Knowing, witty, and possessed of a Zen-like patience, he gives the film an emotional depth and resonance that are a pleasure just to watch.

But I credit Casbah’s success to director John Berry. Back when I reviewed Tension (here ) I cited the strong sense of local atmosphere that film evoked. Well here, Berry does the same thing for the Kasbah. Perhaps he was aided considerably by cinematographer Irving Glassberg, who worked with Douglas Sirk and Anthony Mann at the height of their days at Universal, and by the alluring sets of John DeCuir, who went on to South Pacific and The King and I, but it’s Berry’s sure hand for composition and tracking that lead us dizzyingly through maze-like streets and alleys, in and out of steamy nightclubs and squalid apartments… well, squalid by the standards of a Universal movies — most of them look classier than my old Bachelor digs.

To get back to the Casbah, though, the film comes off with a romantic intensity that surprised me. The songs by Harold Arlen suit the mood splendidly, and there’s even a sultry dance number from Eartha Kitt. And best of all, when we reach the ending we all knew was coming (if we’ve seen the previous versions) Berry does it up with originality and an artistry all his own.

This is not an easy film to find, but if you get a chance, don’t miss it.

Sat 9 Jun 2018

GEORGES SIMENON – The Bar on the Seine. Inspector Jules Maigret #11. Penguin, US, softcover, 2007; translated by David Watson. First published in 1931 as La Guinguette a deux sous (The Tuppenny Bar). First British edition: Routledge, hardcover, 1940, as The Guinguette by the Seine. First US edition: Combined with The Flemish Shop as Maigret to the Rescue (Harcourt, hardcover, 1941). Other reprint titles include Spot by the Seine, Maigret and the Tavern by the Seine, and The Two-Penny Bar (2015). TV adaptations: (1) “The Wedding Guest.” Season 3, episode 4 (15 October 1962) of Maigret (UK), starring Rupert Davies; and (2) “La guinguette à deux sous.” Season 1 Episode 27 (11 October 1975) of Les enquêtes du commissaire Maigret, starring Jean Richard.

This early short Inspector Maigret has a strangely surreal atmosphere to it, heightened by this, the second paragraph:

And the beginning of Maigret’s involvement in the case begins in an odd way, with an interview with a prisoner who is to be executed the next day, in which he tells Maigret of a murder he and a friend saw committed, an incident which they used to blackmail the killer for several years before losing track of him.

He will say no more. The only clue that Maigret has to work on is the killer is one of the regulars at a little bar called the guinguette a deux sous. Not until Maigret overhears a man buying something to wear to a mock wedding and mentioning the bar in passing does he have a foothold in the case.

Somehow getting himself involved with the wedding party, Maigret travels along with them to the place on the Seine where a group of friends congregate for fishing and fun every weekend. One of them is a killer, but who? Maigret watches and listens carefully, then suddenly and unexpectedly a shot rings out. One of the merrymakers is dead, another is standing over him with gun in hand. The latter then manages to make his escape.

For a short novel — only 154 small pages in the Penguin edition — the story is a complex one, as various liaisons between the husbands and wives gradually come to light. More blackmail is involved, based on the latter activity, and it requires some good police work as well as Maigret’s instincts and intuition to bring the case to a solid but very noirish conclusion.

Good detective work, a leading character with some character, and a noirish conclusion. What more could you want in a mystery novel?

Fri 8 Jun 2018

A Movie Review by Jonathan Lewis: SWORD IN THE DESERT (1949).

Posted by Steve under Films: Drama/Romance , Reviews1 Comment

SWORD IN THE DESERT. Universal Pictures, 1949. Dana Andrews, Märta Torén, Stephen McNally, Jeff Chandler. Director: George Sherman.

Sword in the Desert marked Jeff Chandler’s first appearance in a war movie, a film about Jewish resistance fighters during the final days of British rule in Mandatory Palestine. The movie premiered in New York City on April 23, 1949. It remains a milestone both in Chandler’s then still burgeoning screen career and in representations of Israeli national identity, with one observer going so far as to label Sword in the Desert the first within a new American film genre, “the Israeli Film.†The latter would be replicated in American cinema with Edward Dymytrk’s The Juggler (1953) and with the formidable screen presence of Paul Newman as Ari Ben Canaan in Otto Preminger’s commercially and critically successful Exodus (1960).

Although Chandler was not top billed in Sword in the Desert, the film nevertheless demonstrated his natural ability in portraying gruff and laconic men toughened by war and by circumstance, characters faced with numerous obstacles and constrained by difficult choices.

Directed by George Sherman (1908-1991), who later worked with Chandler in two competently directed, but altogether undistinguished, Westerns, The Battle at Apache Pass (1952) and War Arrow (1953), Sword in the Desert is a quixotic and unevenly constructed war film set both chronologically and geographically on the margins of the Second World War. Although most definitely a war film, Sword in the Desert is as much a character study and a compelling drama as an action-packed epic about two opposing factions fighting over the same land.

With a script and production by Robert Buckner, known primarily for his work at Warner Brothers in the 1930s and early 1940s, the movie follows the path, both literally and metaphorically, of Irish-American freighter captain, Mike Dillon (Dana Andrews), the nominal protagonist.

As a smuggler of desperate and impoverished refugees, many of them Holocaust survivors attempting to gain entrance to Palestine, Dillon inadvertently gets mixed up with the Jewish struggle for political sovereignty in the late 1940s Middle East. The British authorities, however, are adamant at stopping the flow of illegal Jewish immigration. So Dillon is able to charge a sizeable fee for his efforts, something he won’t let his initial contact in the Jewish underground, David Vogel (Stephen McNally) forget.

Initially skeptical about any cause larger than his own financial well-being, Dillon ultimately ends up sympathetic to, or at least more understanding of, the Jewish cause in Palestine. It is Chandler’s character, the Israel underground leader, Kurta, who serves as the catalyst for change in Dillon’s personal, political, and spiritual transformation.

This occurs toward the end of the movie, when Dillon refuses to divulge Kurta’s secret identity to the British military authorities. For Andrews, this role, much like the role of a ship’s captain in Sealed Cargo (1951), made him “one of the silver screen’s most decent and desirable leading men.†Indeed, Andrews’s performance in Sword in the Desert, while certainly less known than his work in such films as Laura (1944) and The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), is nevertheless an exceptional one, one that demonstrates skill in conveying both gravitas and world-weariness.

Although Andrews, well into his prime acting years, is a formidable screen presence, it is Chandler’s portrayal of Kurta that remains the highlight of the movie. The viewer first encounters the bronzed, tall, and proudly Jewish fighter some twenty-three minutes into the story. He is taking notes with a pencil while a fellow resistance leader, Sabra, delivers anti-British propaganda over the local airwaves.

Sabra is portayed by Swedish actress Märta Torén, who would go on to co-star with Dana Andrews in the spy film, Assignment – Paris! (1952). After listening intently to Sabra, Kurta speaks. He delivers an impassioned speech about how freedom will come soon to the Jewish people of Mandatory Palestine, ending his broadcast with three poignant words: “God Save Israel.â€

Throughout the film, Kurta proves himself to be both tough and sensitive, determined in his goal to drive the British from Palestine. Although the viewer does not learn whether Kurta was born in Palestine, he does demonstrate all of the characteristics of a Sabra, a euphemism for a native-born Israeli taken from the name of a prickly pear characterized by a tough exterior and soft interior. But Kurta does not allow his idealism to get in the way of his pragmatism. He realizes that he needs Dillon’s assistance in bringing more Jewish refugees past the British naval blockade, and he is willing to overlook the freighter captain’s initial mercenary, if not borderline hostile, attitude toward the Jewish people’s struggle for independence from British control.

On his lapel, Kurta wears a pin in the shape of a sword. It is meant to symbolize Kurta’s status as a leader in the Jewish underground. The film’s title is derived from a poignant scene in which Kurta, surrounded by troops outside Beersheba, drops the sword pin in the desert sand in an attempt to shield his identity from the British forces.

Chandler’s final scene in the movie is both a noble and a tragic one for his character. Wounded badly by gunfire after a controversial and over-the-top sequence in which Jewish commandos raid a British military installation on Christmas Eve, Kurta thanks Dillon for not betraying him to the British authorities. He apologizes to the Irish-American captain for not being able to fulfill his earlier promise to escort him to Beirut so he could get back to his ship. With his final breath, Kurta instructs his subordinate David to ensure that Dillon, now squarely in the pro-Zionist camp, safely gets to Lebanon.

As the first Hollywood film to depict the paramilitary struggle for the contemporary State of Israel, Sword in the Desert is also notable for being one of two movies in which Chandler portrayed an overtly Jewish character, the other the made-for-TV Biblical epic, A Story of David (1960). Although the film barely alludes to the nascent ethno-political conflict between the Zionist movement and Arab nationalism, its political sympathies could not be clearer. One could hardly imagine a major studio today wading into the Middle East conflict with such alacrity and daring.

On the other hand, the film took perhaps one too many liberties with the historical record. This may have inadvertently weakened its chance at getting a wider reception. For instance, the film’s strident depiction of the British military forces in Mandatory Palestine as fundamentally unjust, as opposed to a more nuanced approach, actually weakens the story. Likewise, the historically inaccurate scene in which Jewish commandos attack a British military base does little to move the story forward and may have aided in sinking the movie into obscurity. Not surprisingly, the film’s release was controversial in the United Kingdom, leading at least one London movie theater to shut down a screening due to protests.

While overtly sympathetic to the cause of Israeli national independence, Sword in the Desert was nevertheless geared toward the largely Christian-American movie-going public. This may help explain why Christian symbolism plays such an important role in the movie, such as when Dillon refuses to reveal Kurta’s identity to the British lest he become a “Judas,†the Christmas Eve celebration at the British military compound, and a brief visual reference to the City of Bethlehem at the very end of the film which bolsters the movie’s place within the “Judeo-Christian†tradition.

It might also perhaps explain why Andrews’s character, Dillon, is of Irish heritage, as well as the character, Jerry McCarthy (Liam Redmond), an Irish nationalist who joined the Jewish cause in Palestine primarily as a means of fighting British soldiers. By way of contrast, Kurta never appears to be animated by any particular animus toward the British, so much as by a deep love for the Land of Israel. This helps make his character the most compelling and sympathetic one in the film.