February 2021

Monthly Archive

Sun 14 Feb 2021

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

MICHAEL CONNELLY – The Poet. [Jack McEvoy #1.] Little Brown, hardcover, 1996. Grand Central, paperback, 1997.

A question that most of us rarely have reason or take time to consider is, do we like a series most because we like the character, or because we like the prose? Then someone like Connelly writes his first non-series book, and we have a chance to see. You’ll have to wait a while, though; this has a publication date of January, 1996, but I’d bet [it will be out by] Christmas.

Jack McEvoy is a Denver reporter. His twin brother was a Denver cop, until he killed himself. Jack begins a story on police suicides as a way of dealing with his grief, and discovers a pattern that stretches across the country, and points to a serial killer who is preying on policemen as well as the victims of the crimes they are investigating. Jack seems to be ahead of other reporters and the FBI, but he’s not ahead of the killer.

The [rating of a] double-smiley-plus is for the first 95% of the book, and the frown is for the ending. Connelly is simply an excellent writer in terms of pacing, dialog, and characterization.

I even thought the serial killer was well done, and I’m not much at all for serial killers. This was well on its way to making my best few of the year list, and then came the denouement. Of course I can’t give it away and tell you exactly what the problems were, but I can and will say that there was a double plot twist at the end, and that I found neither necessary and the last just not credible at all.

Why in the hell Connelly thought he needed to do that I do not understand. It didn’t absolutely ruin the book for me, but it left a bad taste in my mouth, and kept it off my “best†list.

— Reprinted from Ah Sweet Mysteries #21, August-September 1995

Sat 13 Feb 2021

ROBERT W. TINSLEY “Smuggler’s Blues.†PI Jack Brady #1. First published in PI Magazine, Spring 1989. Collected in The Brady Files, Kindle edition, 2011.

Jack Brady is a big guy, not easily intimidated. He’s a former Navy SEAL and now a PI whose home base in El Paso TX, which as far as I know is a first among fiction PI’s. At six feet four and 280 pounds, he also finds it difficult to find furniture that fits him. And with El Paso right on the border with Mexico, one suspects that many of the cases he gets involved with involve border incidents of one kind or another.

This first case, “Smuggler’s Blues,†certainly does. Brady is hired by the brother of a man who died while being smuggled across the border, a Salvadoran who had recently been released from prison there for political reasons. The man supposedly drowned, and his death would have been written off as that, if Brady and his client hadn’t interfered.

The story is too short to be more than an incident, and by itself leaves little impression. Brady, who tells the story himself has just enough of a way with words to make the telling enjoyable. Efforts to sound like a tough guy are just a little iffy; a little more “down and gritty†would have helped. Chalk this one down as an early one in Brady’s career.

The Jack Brady stories —

“Smuggler’s Blues” (Spring 1989, PI Magazine)

“Killer” (Winter 1989, PI Magazine)

“Graveyard Shift” (April 2002, HandHeld Crime)

“No Good-Bye” (June 2002, HandHeldCrime)

“Beating On The Border” (Summer 2003, Thrilling Detective Web Site)

“Hijack on the Border” (Oct/Dec 2003, SDO Detective)

“Horse of the Same Color” (Fall 2003, Hardluck Stories)

“Grasshopper” (Winter 2003, Hardluck Stories)

“Double Death” (February 2004, Shred of Evidence)

“A Kiss Is Just A Kiss” (April/May/June 2005, Futures)

“For Felina…” (Winter 2004, Thrilling Detective Web Site)

“Out of the Shadows” (June 2005, Mysterical-E)

“The Horse Holder” (Aug/Nov 2005,Shred of Evidence)

“Sweet Dreams”

“The Prodigal”

“Questioning the Dead”

“The Running Man”

“Moby Dick in a Can”

These last five may be original to the Kindle collection.

Sat 13 Feb 2021

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

UNDER COVER OF NIGHT. MGM, 1937. Edmund Lowe, Florence Rice, Nat Pendleton, Henry Daniell, Sara Haden, Dean Jagger. Screenplay: Bertram Millhauser. Director: George B. Seitz.

Under Cover of Night features Edmund Lowe as a classy cop who matches wits for 24 hours with assorted ambitious academics competing to be named Department Head at a prestigious University. One of them is not above murder, and none of them is above lying, stealing or sleeping around to achieve their ends.

This was written by Bertram Millhauser, who penned some of the better Sherlock Holmes efforts over at Universal, and here manages to make his cast both believably flawed and entirely sympathetic — with the exception of Henry Daniell, who rises to new depths of Nastiness as the Villain of the Piece, a prof who callously tosses a puppy out the window to provoke his wife (on whom he has been cheating while taking credit for her research) into a heart attack.

— Reprinted from A Shropshire Sleuth #73, September 1995.

Sat 13 Feb 2021

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

BRIGITTE AUBERT – Death from the Woods. Elise Andrioli #1. Welcome Rain, hardcover, 2000. Berkeley, paperback, November 2005. Translated by David L. Koral. Setting: Contemporary France.

As the result of a car bomb, Elise Andrioli is a blind, mute quadriplegic. Left by her caregiver Yvette in a park to wait, Elise is befriended by Virginie, a seven-year-old who tells Elise she knows who is killing young boys. When Elise is attacked, she is faced with finding a way to communicate and to stay alive.

Translated from the French, the story, for the most part, flows well and was only occasionally in the dialogue aware of it being a translation. Aubert did a very good job conveying the protagonist’s emotions of frustration, anger, determination, humor and fear. But that was the strength of the book. The plot became more convoluted as it progressed and the ending was anticlimactic as the mystery wasn’t resolved through a series of clues, but by the recitation of one of the characters. So, while I felt the character of Elise was well done, the overall story was only average.

Rating: Good

— Reprinted from the primary Mystery*File website, January 2006.

Bibliographic Update: A second book in the series, Death from the Snows (2001) closed Elise Andrioli’s list of appearances in print, at least to this date. Other crime and suspense thrillers by the author, over a dozen or so, appear to have been published only in France.

Fri 12 Feb 2021

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

REVIEWED BY DOUG GREENE:

TECH DAVIS – Terror at Compass Lake. PI Aubrey Nash #1. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1935. No paperback or other later edition.

This is a better-than-average Golden Age detective novel – indeed as a first novel it shows so much promise that I briefly toyed with the thought that “Tech Davis” may have been the pseudonym of a better-known writer. (No, not JDC; and I’m too uncertain to reveal my candidate.) At any rate, the book is well worth reading.

It begins when a cocky but otherwise featureless young private investigator named Aubrey Nash receives a letter asking him to investigate a locked-room murder at Compass Lake: “If any man was ever sealed into a room and inaccessible, it was Powell and yet in the six hours that we slept someone entered his den, buried a dagger in1 his back, and left.”

Nash however refuses to come. “Three days previously he had completed a case so persistently baffling and so challenging to his health – and even his life – that after solving it he had decided upon Europe and relaxation.” But when Nash receives a second letter telling him not to come, he can’t resist the challenge.

Tech Davis, whoever he was, knew how to structure a book. After this intriguing introduction, the book goes back in time to provide the background events from the viewpoint of one of the characters. It turns out that there has already been an earlier murder, officially labeled a suicide, and like many detective novels written during the depression several minor characters are engaged in financial hanky-panky.

The book includes two maps, one of a plan of the house, the other a drawing of the murder-room. Nash does a good job investigating the crime; the characters are acceptably delineated, and the solutions are good. Experts on locked rooms should be able to solve Powell’s murder more quickly than does Nash, but the book includes a clever, though unlikely, alibi for the first murder.

Terror at Compass Lake shows signs of a neophyte – the middle of the book has too much padding – but I certainly will watch for copies of Davis’s later novels (two of them according to Hubin) about Aubrey Nash.

– Reprinted from The Poison Pen, Volume 4, Number 5/6 (December 1981). Permission granted by Doug Greene.

Bio-Bibliograhic Update: According to the current version of Hubin, we now know that Tech Davis was the pen name of Edgar Davis (1890-1974).

The Aubrey Nash series —

Terror at Compass Lake (n.) Doubleday 1935

Full Fare for a Corpse (n.) Doubleday 1937

Murder on Alternate Tuesdays (n.) Doubleday

NOTE: This book was reviewed by Bill Deeck earlier on this blog. Check it out here. (That review includes one of the maps Doug refers to in this one.)

Fri 12 Feb 2021

RUSSELL BENDER “Heat Target.†PI Dick Ames. Published in Black Mask, October 1936. Not known to have been reprinted or collected.

Richard “Dick” Ames is set up as a full-fledged private eye, with a license, an office, and a secretary. But in reality he’s a troubleshooter with only one client, that being Jonathan McCrea, the mayor of Terrapin City, Maryland. And his work is really cut out for him in “Heat Target,†apparently his only appearance in print. This one’s a doozy.

The boy friend of the mayor’s daughter is the problem. He’s been warned to stay away from Felicia (her friends call her Felix), but they’ve been seen together far too often for the mayor’s liking. But when the young lad turns up dead in his hotel apartment, and the mayor was seen entering at exactly the time of his death, Ames suspects it is an all but iron-clad frame-up, but he can’t prove it.

I liked this one. Bender tells the resulting tale, one chock full of a lot of shootings and other crooked business going on, with a terse, hard-bitten prose that does nothing more than remind you that there’s a reason why Black Mask is considered the best there was when it came to detective pulps in the 20s and 30s.

Here’s a lengthy description of Ames himself:

“He was a large, indolent looking man, broad of shoulder, slim of waist; but the indolence was in the careless grace of his walk, in th manner in which he slouched on a chair, slouched against tables, bars, telephone poles. He had a rugged face. There was a strength about him, but it was the strength of a dozing, stretching lion. His movements were slow but you knew instinctively that he could move as fast as hell.â€

I think I might have cast Robert Mitchum in the role if they’d ever made a movie of this one.

Strangely enough, while Russell wrote quite a few stories for the detective pulps, he wrote only two others for Black Mask: “Body-Guard to Death,†(novelette) October 1938 and “Copper’s Moll,” (short story) July 1940. Based on this one only, I’d have thought there’d have been more. There should have been.

___

Note: Some other information about Bender can be found in the comments following Paul Herman’s recent overview of the entire issue of the October 1936 Black Mask.

Thu 11 Feb 2021

X MARKS THE SPOT. Republic Pictures, 1942. Damian O’Flynn as PI Eddie Delaney, Helen Parrish, Dick Purcell, Jack La Rue, Neil Hamilton, Robert Homans, Anne Jeffreys, Dick Wessel. Co-screenwriter: Stuart Palmer. Director: George Sherman. The movie can currently be seen online here.

Just two days before he’s off to help fight the war, the father of PI Eddie Delaney is killed while on duty as an on-the-beat policeman. Grieving, Delany is given a chance to do something about it when he’s hired by a man to look into a case of trucks being hijacked while loaded with tires. Rubber being at a premium in the early days of the war, this is no trivial matter.

And besides working on the case, Delany senses a connection between it and his father’s death. His dad, he thinks, stumbled across something he shouldn’t have, and it cost him his life.

That’s about the extent of the plot, but the 52 minutes of running time is filled to the brim. Besides at least three deaths (I may have lost count), a budding romance between Delaney and Linda Ward (Helen Parrish) as one of the girls working at the headquarters of a citywide telephone jukebox system, and of course she helps him out with the case he’s on.

As a detective story, the screenwriters had a tough job keeping the killer’s identity a secret, with all of the suspects being killed off, one by one. By the time the last reel is shown, there are no suspects left.

The cast consists of players who have no name recognition today, and they may not have even back then. I sometimes wonder if they might not even be recognized by people such as ourselves who watch movies such as this one and go look them up on IMDb as soon as the movie is over.

Centralized telephone jukebox systems have come up for discussion on this blog before, that so happening as part of my review of Swing Hostess (1944), starring Martha Tilton, and the comments following. Here’s the link: Click here.

More details on such an operation and better photos from X Marks the Spot can be found here: Click here.

Thu 11 Feb 2021

SELECTED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

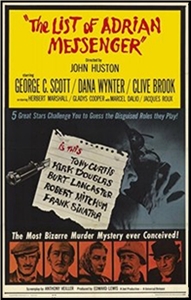

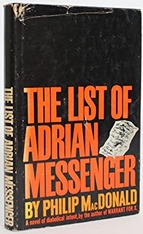

PHILIP MacDONALD – The List of Adrian Messenger. Col. Anthony Gethryn #12. Doubleday, US, hardcover, 1959. Bantam A2186, US, paperback, 1961; #F2643, 1963. Herbert Jenkins, UK, hardcover, 1960.

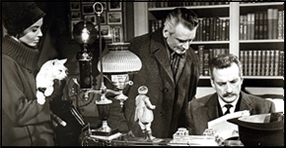

THE LIST OF ADRIAN MESSENGER. Universal-International, 1963. Kirk Douglas, George C. Scott, Dana Wynter, Jacques Roux, Herbert Marshall, Clive Brook, Gladys Cooper Guest Stars: Tony Curtis, Burt Lancaster, Frank Sinatra, Robert Mitchum. Screenplay by Anthony Veiller. Directed by John Huston. Available on DVD.

The tale hinges, like so much in humanity’s sorry history, on a piece of paper. In this case no broken treaty or injudicious epistle from one Personage to another, but a slip upon which Adrian Messenger wrote the names and addresses and occupations of ten men.

When writer Adrian Messenger asks a friend to use his influence to look into a disparate list of men from all walks of life and all parts of the United Kingdom it seems like nothing but a whim, but shortly after, when Messenger is killed in a plane crash the friend in question turns to Anthony Gethryn to look into the list, almost immediately one fact arises, all ten men died of untimely accidents, including Adrian Messenger, making for a strangely coincidental eleven accidental deaths seemingly unrelated deaths.

Semi-amateur sleuth Col.Anthony Gethryn (The Rasp, Warrant for X) suspects something, and with the help of one of the survivors, a Frenchman, Raoul St. Denis, who coincidentally was once a member of the French Resistance run by Gethryn anonymously in the war, it soon becomes apparent Adrian Messenger was onto something sinister and deadly.

At first Gethryn’s friend at the Yard, Lucas, and his old ally Inspector Pike, think Anthony is jumping at conclusions, but between a dying message left by Messenger in the lifeboat with St. Denis, and an expanding investigation it becomes clear there is a killer on the loose, one who has carefully over the years eliminated anyone who might know him for an as yet unknown reason.

A series, if not serial, killer who eventually tallies sixty seven murders over much of the globe, all disguised as accidents, a criminal genius who only has two more deaths to go, an old man and a fourteen year old boy, the Marquis of Gleneyre and his grandson, heirs to a considerable fortune.

Worse, there may be nothing the law can do to stop him.

The List of Adrian Messenger is the final novel in the Anthony Gethryn series that began at the height of the Golden Age of the Detective Novel from a writer whose books such as The Rasp, Warrant for X, Escape, Mystery of the Dead Police (X vs Rex), and Patrol led him to Hollywood and a long career as a screenwriter penning everything from Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto to Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca.

It is not the end of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction; writers such as Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh, John Dickson Carr, and John Rhode, not to mention Ellery Queen and Rex Stout in this country, continued to write for sometime after MacDonald’s death. Still it is coda to the era, and works both as a fair play mystery novel, and not unusual for MacDonald, as a suspense novel and a thriller, making it a compellingly readable mix of the old and the new.

Series killers, even serial killers, weren’t new to the Classical Detective story. Christie’s The Alphabet Murders, Conan Doyle’s Sign of the Four and A Study in Scarlet, MacDonald’s own Mystery of the Dead Police and Murder Gone Mad and the plot here has some interesting ties to MacDonald’s plot for his original screenplay for Circle of Danger in the motive for the killer.

What interests me here is where the 1959 novel and the fine 1963 film by John Huston vary, because while the Huston film uses large chunks of dialogue directly from the novel it varies importantly from the book on one key point, one that puts Anthony Gethryn in the mainstream of the high handed Great Detective model and ironically sets him against the entire genre.

So at this point:

Spoiler Warning!

Spoiler Warning!

Spoiler Warning!

One of the key personality traits of the Great Detective has always been his high handed behavior, hiding key facts from his Watson, playing God (almost all the Ellery Queen novels after The Door Between are concerned with Ellery’s unease playing God in his role as Great Detective), and acting as a figure of justice and vengeance and not merely law. When Sherlock Holmes at the end of “The Speckled Band†mused he wasn’t much bothered by the fact his actions led to the death of the brutal doctor Conan Doyle could hardly have imagined how many writers would take it to heart.

Philo Vance practically encouraged the murderers he caught to commit suicide. Even Charlie Chan saw quite a few of his killers dying by their own hand rather than waiting for a messy trial and even Agatha Christie’s seemingly cozy Miss Jane Marple defined herself as Nemesis and not merely a puzzle solver. John Dickson Carr’s Dr. Gideon Fell burns down a house to keep the police from charging a murderer in The Man Who Could Not Shudder to avoid a miscarriage of justice.

But few act as decisively as Anthony Gethryn does here.

In the film, as in the book, the killer, George Brougham (Kirk Douglas), is known about half way through the book, but he has left no trail. The police have nothing but suspicions, and short of catching him in the act, and nothing suggests he will be that stupid, he only needs to wait patiently to kill the fourteen year old heir who simply cannot be watched for the rest of his life.

Knowing that Anthony Gethryn (George C. Scott) deliberately lets Brougham know that he is close to uncovering his secrets and forces him to try to kill Gethryn, the attempt, and Brougham’s fate sealed at a fox hunt (which plays a large part in film and book though more so in the film because director Huston was devoted to riding to the hounds on his Irish estate) Brougham meeting a satisfyingly grim justice impaled on a farm implement he meant to use to kill Gethryn.

At which point the film pauses to show us the clever make up disguises used by Douglas and his four major guest stars.

And this is where the movie lets down fans of the book somewhat, because the ending of the book is considerably more stunning, Gethryn telling Lucas after he has seemingly walked away from the case.

“When I told Outram that George Brougham was an extraordinary criminal, and the police didn’t have the extraordinary powers need to deal with him, I was implying that he would have to be dealt with by some person or persons who weren’t bound by a book of rules.â€

Gethryn doesn’t just set a trap to capture Brougham, though he does use the young Marquis as bait to catch Brougham in the act, he knows that short of allowing Brougham to kill the boy in front of witnesses the law has almost no case, so Gethryn, St. Denis, members of the French resistance, Hispanic allies and friends of Gethryn, and the Marquis and Adrian Messenger’s cousin Jocelyn (Dana Wynter in the film) lure George Brougham to California and arrange for him to be hoist on his own petard, to die in an accident while fleeing a foiled attempt to kill the boy.

In short they conspire to and successfully execute George Brougham, by “accident,†or as St. Denis notes in the books final line, “What you would call, I think, a justice poetic…â€

I think it is that ending that gives the novel a unique place in the history of the Golden Age of the Fair Play Detective novel. The world has changed, and murder is no longer committed by gentlemen who can be expected to conveniently put a bullet in their own brain rather than face trial, imprisonment, and shame.

George Brougham has no shame. He is a modern killer, amoral, a sociopath, a cunning murderer willing to kill dozens to achieve his goal. He is evil, but a more mundane and frightening kind of evil than a Fu Manchu or a Moriarty. He is a human monster born out of WW II, ruthless, clever, and above the ability of the law to stop him.

The oh so civilized rules of the Golden Age Detective Novel have broken down and no longer apply, it is no longer just a game. The victims are ordinary men and potentially a boy who has harmed no one. The killer is as amoral and efficient as the monsters who marched millions into ovens to die in death camps, and his motive isn’t political, it’s money and power.

To defeat him, Anthony Gethryn has to forgo the academic and cool analytic of the Great Detective he becomes an avenger as much as a Bulldog Drummond, James Bond, or Mike Hammer, an agent of chaos and not order, the classical role of the Great Detective.

Hercule Poirot will find himself in the same role in his final adventure, Curtain. It is a concession of the Golden Age to the modern world. The brain and the intellect is not enough in the face of evil, the dragon must be met on his own level. Which at least, for me, makes The List of Adrian Messenger a fairly revolutionary statement from one of the masters of the Golden Age puzzle.

Murder is no longer a game and its victims no longer pawns. That idea that real people are dying and murderers walk among us is almost more than the fragile conceit of the Golden Age can bear.

I think a fairly good argument can be made MacDonald was putting the audience and his fellow writers on notice that the cozy comfortable world they created was no longer enough for readers and no longer sustainable as mystery fiction. You have to wonder whether he would have carried Gethryn beyond this point if he had lived longer, or if he had said all that could be said about the Great Detective from his point of view.

Wed 10 Feb 2021

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Susan Dunlap & Marcia Muller

AGATHA CHRISTIE – The ABC Murders. Hercule Poirot #13. Dodd Mead, US, 1936. First published in the UK by Collins, hardcover, 1936. Reprinted many time, in both hardcover and paperback. Film: MGM, 1966, as The Alphabet Murders, with Tony Randall as Hercule Poirot. TV adaptations: (1) As an episode of ITV’s Agatha Christie’s Poirot (1992) with David Suchet as Poirot. (2) BBC, three part mini-series, 2018, with John Malkovich as Hercule Poirot

Agatha Christie has long been acknowledged as the grande dame of the Golden Age detective-story writers. Beginning with her moderately successful The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), Christie built a huge following both in her native England and abroad, and eventually became a household name throughout the literate world. When a reader – be he in London or Buenos Aires – picks up a Christie novel, he knows exactly what he is getting and has full confidence that he is sitting down to a tricky, entertaining, and satisfying mystery.

This enormous reader confidence stems from an effective combination of intricate, ingenious plots and typical, familiar characters and settings. Christie’s plots always follow the rules of detective fiction; she plays completely fair with the reader. But Christie was a master at planting clues in unlikely places, dragging red herrings thither and yon, and, like a magician, misdirecting the reader’s attention at the exact crucial moment. Her murderers – for all the Christie novels deal with nothing less important than this cardinal sin – are the Least Likely Suspect, the Second Least Likely Suspect, the Person with the Perfect Alibi, the Person with No Apparent Motive. And they are unmasked in marvelous gathering-of-all-suspects scenes where each clue is explained, all loose ends are tied up.

As a counterpoint to these plots, Christie’s style is simple (even undistinguished). She relies heavily upon dialogue, and has a good ear for it when dealing with the “upstairs” people who are generally the main characters in her stories: the “downstairs” people fare less well at her hands, and their speech is often stilted or stereotyped.

Christie, however, seldom ventures into the “downstairs” world. Her milieu is the drawing room, the country manor house, the book-lined study, the cozy parlor with a log blazing on the hearth. Like these settings, her characters are refined and tame, comfortable as the slippers in front of the fire – until violent passion rears its ugly head. Not that violence is ever messy or repugnant, though; when murder intrudes, it does so in as bloodless a manner as possible, and its investigation is always conducted as coolly and rationally as circumstances permit. One reason that Christie’s works are so immensely satisfying is that we know we will be confronted by nothing really disturbing, frightening, or grim. In short, her books are the ultimate escape reading with a guaranteed surprise at the end.

Christie’s best-known sleuths are Hercule Poirot, the Belgian detective who relies on his “little grey cells” to solve the most intricate of crimes; and Miss Jane Marple, the old lady who receives her greatest inspiration while knitting. However, she created a number of other notable characters, among them Tuppence and Tommy Beresford, an amusing pair of detective-agency owners, who appear in such titles as The Secret Adversary (1922) and Postrn of Fate (1973); Superintendent Battle of Scotland Yard, who is featured. in The Secret of Chimneys (1925), The Seven Dials Murder (1929), and others; and the mysterious Harley Quin.

The member of this distinguished cast who stars in The ABC Murders is Hercule Poirot. Poirot is considered by many to be Christie’s most versatile and appealing detective. The dapper Belgian confesses gleefully to dying his hair, but sees no humor in banter about his prized “pair of moustaches.” And yet he has the ability to see himself as others see him and use their misconceptions to make them reveal themselves and their crimes.

A series of alphabetically linked letters are sent to Poirot, taunting him with information about where and when murders will be committed unless he is clever enough to stop them. The aging detective comes out of retirement, he admits, “like a prima donna who makes positively the farewell performance … an infinite number of times.” Is the murderer a madman who randomly chooses the victim’s town by the letter of the alphabet, or is he an extremely clever killer with a master plan? And why has he chosen to force Poirot out of retirement?

These questions plague Poirot’s “little grey cells” as the plot thrusts forward and then winds back on itself time and time again. Well into the novel, Christie teases the horrified reader by introducing a coincidence that looks as if it will solve the cases, then snatches it back, dangles another possibility, snatches that one back, too. And so on, until the innovative and surprising conclusion is reached. Poirot is al his most appealing here, and Christie’s plotting is at its finest.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Wed 10 Feb 2021

Posted by Steve under

General[4] Comments

Quiquid latine dictum sit altum viditur.

« Previous Page — Next Page »