January 2023

Monthly Archive

Fri 13 Jan 2023

GROVER AVENUE BLUES:

The 87th Precinct TV Series, Part One

by Matthew R. Bradley.

Under the byline Evan Hunter, legally adopted in 1953, Salvatore Albert Lombino (1926-2005) was the original author and/or screenwriter of such films as The Blackboard Jungle (1955), adapted by director Richard Brooks; John Frankenheimer’s The Young Savages (1961); and Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963). His scripts and stories were seen on Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Kaiser Aluminum Hour, and Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre.

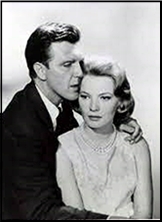

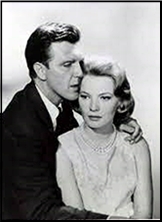

As Ed McBain, he was the acknowledged master of the police procedural, his 87th Precinct mysteries comprising 55 books over half a century, possibly inspiring Hill Street Blues. Cop Hater, The Mugger, and The Pusher (all 1956) were filmed between 1958 and 1960; the following year, NBC’s 87th Precinct debuted. Robert Lansing, carried over from The Pusher (1960), played Det. Steve Carella, and later Gary Seven in the Star Trek spin-off manqué “Assignment: Earth†(3/29/68).

In a 1989 introduction to Cop Hater and afterword to The Pusher, McBain discussed his innovation of a “conglomerate hero in a mythical city…[that] was like New York but not quite New York,†with analogs for each borough. “[O]ne cop can step into the spotlight in one novel, another in the next novel [as when Carella is honeymooning in The Mugger], cops can get killed and disappear from the series, other cops can come in, all of them visible to varying extents…†The show standardized the duty roster to Carella and three colleagues, replacing “Isola†with its model, Manhattan.

Ron Harper — later astronaut Alan Virdon on Planet of the Apes — co-starred as Bert Kling, promoted from patrolman after cracking a murder in The Mugger. The landlord on Three’s Company, Norman Fell played sardonic family man Meyer Meyer, per McBain “a Jew whose father had a hilarious sense of humor.†Immortalized in Ed Wood’s Plan 9 from Outer Space (1957), Gregory Walcott was the sanitized Roger Havilland, whose prose original tried to break up a street fight; broken in four places by a lead pipe, his arm had to be rebroken and reset, said ordeal rendering him a violent cynic.

◠Of the 30 episodes, 11 were based on McBain’s works, including all nine novels following The Pusher; “The Floater†(9/25/61) was adapted from The Con Man (1957), previously dramatized on Climax! as “The Deadly Tattoo†(5/1/58). The 87th Precinct premiere was written by Winston Miller, who went on to co-produce the series with Boris D. Kaplan, while Alfred Hitchcock Presents and Thriller workhorse Herschel Daugherty directed the first and last episodes. This introduced Carella’s deaf-mute spouse, Teddy (Gena Rowlands), and medical examiner Dr. Tom Blaney (Paul in the novels; Dal McKennon).

Robert Culp guest-stars as serial killer Curt Donaldson, who selects prospective wives with personals ads, gains control of their money, and dispatches them with arsenic after “signing his work†with distinctive tattoos. Teddy plays a prominent role, following Curt and his latest victim from a tattoo parlor to Pier 7, where she is almost killed before the squad arrives to save both women. Havilland provides a vastly toned-down account of McBain’s transformative trauma, while the lethally affable Culp was followed by such up-and-comers as Dennis Hopper, Leonard Nimoy, Robert Vaughn, and Peter Falk.

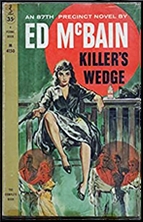

◠McBain personally scripted “Lady in Waiting†(10/2/61) and “King’s Ransom†(2/19/62); adapted from Killer’s Wedge (1959), the former marked Rusty Lane’s debut as Desk Sergeant Dave Murchison. Virginia Colt (Constance Ford) holds the disarmed Meyer, Kling, and Havilland hostage at the station house — located, per McBain, on Grover Avenue, facing Grover Park — with a bottle of alleged nitroglycerine, vowing to kill Carella on arrival for sending her safecracker husband to prison, where he has died.

Stumbling in, clerk Alf Miscolo (Miguel Landa) is shot, concealed, and denied a doctor as Roger turns off the fan, closes the windows, and cranks up the thermostat, prompting Virginia to remove the coat in which she pocketed his gun. Teddy arrives as Roger goes for his weapon, and Meyer pretends she is a complainant, but Virginia recalls reading of Mrs. Carella’s disability, and threatens her before being subdued in a scuffle by Roger and Bert. Delayed by a flat, Carella is baffled by the Bomb Squad’s call to say, “it was.â€

Dropping Teddy’s pregnancy and the B story of Steve’s locked-room “suicide,†McBain nicely depicts the squad’s ingenious efforts at extrication, defeated by stupidity. Bert slyly tries to summon help while answering a call from the precinct commander, who is oblivious to his hints; assuring a clueless Dave that the shot he heard was accidental, Meyer says he’ll see the sarge “forthwith,†police jargon for “report immediatelyâ€; Meyer is pistol-whipped by Virginia when she listens in on an imprudent call from Headquarters after two boys find a note he slipped out the window. McBain also retains his sympathetic portrayal of a Puerto Rican immigrant arrested for slitting the throat of a man who “got funny†with her.

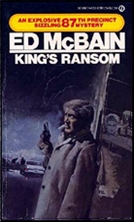

◠“King’s Ransom†was based on McBain’s 1959 novel, filmed by Akira Kurosawa as Tengoku to jigoku (Heaven and Hell, aka High and Low; 1963). Businessman Douglas King (Charles McGraw) faces an ethical dilemma when his chauffeur’s son, Jeff (Buzz Martin), is mistakenly kidnapped instead of his own, and Sy Barnard (Tony Carbone) demands that he pay regardless. Needing the money he has raised for a boardroom power struggle, King shocks his wife, Diane (Nancy Davis), by refusing to pay, but is advised to play for time by saying he will.

With Carella on the floor in the back, King is given the runaround by Sy’s accomplice, Eddie Folsom (Charles Aidman), transmitting by radio to his car phone to direct him to a drop-off for Sy. But Eddie’s wife, who wants nothing more than a fresh start in Mexico, fears that Sy plans to kill Jeff either way, so she blurts both their location and his into the open mike, and when the hideout is raided, Jeff repays her kindness by insisting he’s been alone since Sy left. This exceptionally well-cast episode makes the boys 18, rather than 8, and when the Kings tell Carella that Doug’s power grab succeeded, we learn the Folsoms were caught, unlike in the book.

◠Faithfully adapted by John Hawkins from the 1958 novel, “Lady Killer†(10/9/61) introduces department psychiatrist Ben Daniels (Harlan Warde); Sam Grossman (Michael Fox), who runs the police laboratory; and his technician, Joe Richards (Dennis McCarthy). Taking a complaint, Kling barely notices when Frankie Annuci (Billy Hughes) — paid $2 by an unknown man — delivers a pasted-up note reading, “I will kill The Lady tonight at 8. What can you do about it?†Carella sees binoculars glinting from a roof across the street, so Bert slips out back to investigate, but is clouted before getting a good look at the perp.

Meyer learns that the purchaser of the dropped glasses may have lost them at the 708 Club, yet Frankie says he isn’t the man, and works with a sketch artist. Checking tenements, Meyer learns that the sketch may match tenant “Mr. Smith,†who fires on him and flees; he finds cards from the Jo-George diner, where George Ladonna (Peter Leeds) says partner Jo Cort (Lee Krieger) took a few days off. With George headed for drinks at 8:00 at the nearby 708, Carella remembers “la donna†is Italian for “the lady,†and they arrive just in time to save George, who loyally denied recognizing the sketch, thinking that Jo — jealous because his ex-girlfriend prefers George — was in routine trouble.

◠The first of Norman Katkov’s two adaptations, “Killer’s Payoff†(11/6/61) was based on McBain’s 1958 novel and directed by John Brahm, like Daugherty a mainstay of the Hitchcock series and Thriller. Slain blackmailer Hank Richards paid for an apartment for dancer Nancy Johnson (Beverly Garland), from whom Havilland gets his “client list.†Kling overhears ex-model Lucy Mencken (Jeanne Cooper), shielding her husband from racy photos, make a rendezvous with Hank’s would-be successor, but following her, Roger is pistol-whipped.

Havilland’s questioning provokes an angry visit in which Hank’s friend Marty Torr (Paul Richards) slaps Nancy around, admitting that he killed Hank and then followed the cops to identify his marks. He’s about to shoot Nancy when Roger calls to invite her to dinner, and her cleverly off-kilter reply cues him to go in with gun blazing. McBain’s far more convoluted solution involved a “conglomerate perp,†three hunters whom the blackmailer saw accidentally kill, and bury, a fourth; they joined forces to shoot him, and almost claim the life of the detective trying to trap them.

◠Adapting “’Til Death†(12/11/61) from McBain’s 1959 novel, Katkov turns Steve from an expectant father (of twins born on the last page) and the brother of bride Angela (Judi Meredith) into a family friend. Tommy Palmer (Darryl Hickman) and Angela receive deliveries containing, respectively, a black widow and condolence card. Marty Kellogg (Johnny Seven), who blamed Tommy for a buddy’s death in Korea, was just released from a veterans’ hospital, so Kling agrees to attend with his fiancée, Claire Townsend (Margie Regan), in tow.

Dancing with Angela at the reception, best man/long-ago beau Ben Darcy (Corey Allen) says it should have been theirs, and he’ll be there if anything happens to Tommy; overhearing, Steve confirms Ben’s handwriting on the delivery cards, which he says were jokes. Marty arrives, professing no hard feelings, but clocks Kling, who was searching for him, and attacks Tommy with a switchblade, stopped by Steve in the nick of time. Katkov streamlines McBain’s bizarre plot, putting commendable focus on emotions and relationships.

◠Richard Collins wrote three adptations, starting with “Empty Hours†(11/20/61), which was shorn of the initial article from a novella published in Ed McBain’s Mystery Book #1 (1960) and the titular 1962 collection. Claudia Davis drowns when Eric Blau (William Schallert) fires at her canoe on Triangle Lake, while onshore companion Josie Thompson (Patricia Crowley) — oblivious to the silenced shots — tries to save her. Penniless Josie, reported drowned, has her hair cut and dyed, telling fiancé George (Henry Brandt) that their uncanny resemblance will enable her to claim her best friend’s inheritance.

Blau’s employer says “Claudia†is writing checks that lead Steve and Bert to a witness, recompensed for workdays the inquest cost him, and a passport photographer; records also reveal a traffic violation. The embezzling executor asks “Claudia,†unseen since childhood, to refrain from drawing interest, citing an investment tip, and has Blau try again, but questioning a cabbie hired to drive “Claudia†— who didn’t know how — back to town tips off Carella and Kling in time to stop him. Inventing Blau, George, and the executor, Collins here takes the greatest liberties with McBain’s source, which opens with “Claudia†found strangled by a panicked burglar.

◠In “The Heckler†(12/18/61), Collins masterfully distills the 1960 novel introducing the precinct’s Moriarty, the Deaf Man, aka Sordo; with the iciness he later showed in Bullitt (1968), Robert Vaughn is perfect as the ruthless, methodical villain. His complex scheme involves death threats to a man whose loft is above the soon-to-relocate Mercantile State Bank, and to others located near lucrative businesses. Distracting the police with those and bombs made by night watchman “Pop†Smith (Frank Albertson), he hopes to heist more than $1 million from the the vault in the new location, under which he has tunneled during construction.

Learning that Pop concealed a fiancée, Sordo coldly shoots him, but a hotel matchbook found in his burned uniform leads to Lotte Constantine (Mary La Roche); Kling catches her retrieving love letters from his apartment and finds a bank floor plan before Sordo — who learned Pop copied it — bursts in to wound Bert. Sordo follows with the kidnapped Lotte while his henchmen take the loot to the ferry in an ice-cream truck. Disembarking after a family vacation, Meyer accosts the driver over a license-plate discrepancy, but timely warnings from his wife, Sarah (Ruth Storey), and Lotte allow him to disarm the thieves.

◠Scripted by Luther Davis and Collins, “Killer’s Choice†(3/5/62) was based on McBain’s 1957 novel, previously an episode of Kraft [Mystery] Theatre (6/11/58). That and another live Kraft entry — Larry Cohen’s original teleplay “87th Precinct†(6/25/58) — were the first attempt at a series, with several cast members in common; Cohen later wrote the telefilms Ice (1996), based on McBain’s 1983 novel, and Heatwave (1997), another original. Amy Boone (Gloria Talbott) is found shot dead in the liquor store where she worked for Franklin Phelps (R.G. Armstrong), with whom she was having an affair.

“It sounds like we’re talking about three different people,†Kling says when the squad compares accounts by her mother, ex-husband, and other “friendâ€; Mrs. Phelps is tricked into admitting she killed Amy, having slipped away from a Miami party and taken a round-trip flight to New York. In the novel, McBain introduced Det. Cotton Hawes and killed Havilland with the shards of a plate-glass window through which a perp pushed him, a B story incorporated into “New Man in the Precinct†(4/16/62), supplanting Havilland. (McBain’s Pusher afterword reveals he wanted Carella to succumb to gunshots there, but was dissuaded by his agent and editor.)

◠Written by Robert O’Brien and James Gunn, “New Man†finds Cotton (Fred Beir) filling in from the ritzier 30th for vacation-bound Det. Frank Kanin (Ray Montgomery), who meets the literary Havilland’s fate. He stops to help stricken Matt Murdock (Robert Colbert), winged by Dave Evans (Max Slaten) after breaking his jaw with a left hook in a liquor-store robbery; noticing the blood, Frank gets the same, hurled to his death. Carella checks out ex-pugs in trouble with the law, and Evans identifies Murdock, who persuades a doctor to remove the bullet, although daughter/nurse Linda Walters (Elizabeth Perry) warns it’s illegal not to report it.

Social Security leads Carella and Hawes to Murdock’s hotel, but Cotton naively knocks on the door, eliciting a hail of bullets that nearly kills Steve. His wound reopened, Murdock blackmails Linda into coming to his new digs to patch it up, with a penicillin chaser, yet when the clerk spots his newspaper photo and drops a dime, the syringe is found. Bluffed to believe her father’s prints are on it, Linda recalls Murdock’s unusual phraseology regarding his getaway, a trucking company’s marketing slogan; the squad apprehends him at the depot, and Hawes learns that Steve is not one to hold a grudge.

◠In “Give the Boys a Great Big Hand†(1/15/62), adapted by Shimon Wincelberg from McBain’s 1960 novel, a severed hand in a flight bag from Las Vegas sends Bert to Missing Persons, where he’s offered the file on stripper Barbara “Bubbles†Caesar as a diversion. Kling and Carella investigate merchant seaman Karl Andrade (Michael Forest), who stormed out on learning of Milly’s (Suzi Carnell) pregnancy. He got drunk, and a previous flame — whose photo Bert recognizes as Bubbles — called to say he was there, asleep, but Karl claims it’s all over between them.

Choreographer Warren Tudor (Barry Atwater) brought his “soul mate†from Vegas and hated the baser attentions she received at the club where drummer Mike is also missing; Karl wants her to convince Milly nothing happened, and sets up a meeting at Tudor’s, but it’s a trap. Carella and Kling arrive just in time to prevent Tudor from chopping off the hands that “defiled my love†with a sword, finding Barbara and a mutilated Mike, both killed when caught in flagrante delicto by Tudor, who deludes himself that she is still alive. Wincelberg ends on a more positive note with the Andrades reconciling, whereas McBain’s unsympathetic seaman, obsessed with Bubbles, planned to abscond with her.

— Copyright © 2023 by Matthew R. Bradley.

END OF PART ONE: TO BE CONTINUED …

Fri 13 Jan 2023

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

THOMAS B. DEWEY – Death and Taxes. Mac #14. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, hardcover, 1967. Berkley, paperback, May 1968.

This one starts out the way a good old-fashioned PI story should – no, I’ll take that back. Any good PI story should start with a good-looking blonde entering the PI’s office as a would-be client. But consider this as the next best thing:

They shot Marco Paul on June 18 at 2:15 in the morning, in an alley behind a place called Ezra’s on the Northeast Side.

Given that Marco Paul having been an old-fashioned Chicago gangster for most of his life, and this is an old-fashioned hit straight out of Black Mask Magazine, you might even decide that this is a better first sentence than the worn-out Gorgeous Blonde Client Gambit.

And as it turns out, Marco Paul is/was on the verge of becoming Mac’s client. What Paul wanted Mac to do is make sure that his daughter gets the million dollars in cash he has stashed away for her, tax-free.

So far, Mac has said he’d think about it. Does he know where the million dollars is? No. They hadn’t gotten around to that. Do other parties (both friends — some closer than others — and family) think he knows where the million dollars is? Yes, and they become actively involved in finding out where it is.

At one point along the way Mac is severely tortured and beaten. Does he recover in the very next scene and carry on as usual, as a certain detective named Joe Mannix always did after being conked on the head? No. Definitely not. This is real life that Mac is living through, and real life often hurts.

I mentioned Black Mask a short distance upstairs. This reads – or at least the first half does – like a finely tuned Black Mask story, a little more literate and a little more polished, perhaps, and it is a lot of fun to read. Unfortunately when it comes time to pull all of the plot threads together, Death and Taxes becomes a lot more standard type of PI tale, with lots of guns blazing away and a lengthy explanation of who did what to whom and when.

I going to call it a mixed bag, then, and let you decide, once you take me up on this proposition, to read this for yourself and tell me which half you preferred.

Thu 12 Jan 2023

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

REVIEWED BY BOB ADEY:

SIMON JAY – Death of Skin Diver. Collins, hardcover, 1964. Doubleday Crime Club, US, hardcover, 1964.

The author’s first book and he only wrote one more. Set in New Zealand, it opens with the accidental drowning of a skin diver – or at least it appears to be accidental until absent-minded detective, Dr/ Peter Much, a practicing pathologist, notices one or two inconsistencies and follows them up.

More violence and death follow, and Much is nearly killed himself. There is mysterious sea chase (and endpaper map to illustrate it), and the unusual crime of gin running (yes, that’s right, gin not gun) is at the bottom of it all.

By no means a classic, but nonetheless well worth searching out for Dr. Much and his haphazard detection.

– Reprinted from The Poisoned Pen, Volume 4, Number 4 (August 1981).

Bibliographic Update: Simon Jay’s second and only other mystery novel was Sleepers Can Kill (Collins, 1968). Unfortunately, there is no indication in Hubin that Dr. Much made a second appearance in it.

Wed 11 Jan 2023

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

J. D. KIRK – A Litter of Bones. DCI Jack Logan #1. Zertex Crime, hardcover, October 2020. Setting: Scotland.

First Sentence: The total collapse of Duncan Reid’s life began with a gate in the arse-end of nowhere.

The past comes back to haunt DCI Jack Logan. A boy has disappeared, and the case has all the characteristics of “Mister Whisper,” a serial child-killer Logan put away ten years ago. When another child goes missing, Jack is sent to lead the investigation. Did Jack have the wrong man all those years ago? Is this a copycat. Either way, Jack needs to do everything possible to rescue the boy.

It takes very little time to recognize the quality of Kirk’s writing and his skill for dialogue. He provides a well-done introduction to Logan’s team and their personalities. Sinead and DC Hamza Khaled are particularly well utilized in their roles.

One appreciates the hints of humour with their very Scottish flair— “But in a minute, I’m going to hear a cry for help from within this house, giving me no choice but to break this door down and investigate.” …Sinead hesitated, then nodded. …He watched as Sinead leaned past him, turned the handle, and pushed the door open. “It’s the Highlands,” she told him. “We don’t always lock our doors.” What a good example of Logan being out of his element while showing his fallibility.

Kirk establishes an excellent sense of place, whether it be a small, mid-terrace house, or the open area. Yet it is the excellence of conveying the fear and frustration of the family which are particularly compelling. His ability to escalate suspense is palpable, cementing the plot as being a ripping page turner filled with wicked twists. Be aware that there are scenes related to animal torture, and others not for the faint of stomach.

A Litter of Bones is a straight-through, non-stop read filled with great characters, action, suspense, emotional impact, twists and just enough humor for balance. There are no portents, just a wicked good story that keeps on turning the pages. It is dark, and there are scenes unpleasant to read, yet the positive qualities outweigh the negative and compel one to read the next book.

Rating: Excellent.

Tue 10 Jan 2023

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

RAYMOND CHANDLER – Farewell, My Lovely. Philip Marlowe #2, Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1940. Reprinted many times.

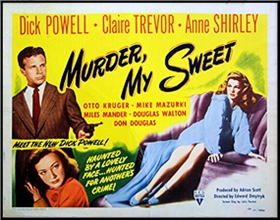

MURDER, MY SWEET. RKO, 1944. Dick Powell, Claire Trevor, Anne Shirley, Otto Kruger, Mike Mazurki and Miles Mander. Screenplay by John Paxton, from the novel Farewell, My Lovely, by Raymond Chandler. Directed by Edward Dmytryk.

I like to get back to Raymond Chandler once a year or so, and late last year it was Farewell, My Lovely (1940) a fun read enlivened by Chandler’s polished prose and feel for violence. This is the one with Marlowe getting knocked around by Moose Malloy — a character who seems to have inspired the Incredible Hulk — then waking up in a sanitarium for more sadistic fun. Add some engagingly corrupt cops, stolen whoosis and the inevitable near-fatale femme and you get a book that set the standard for a whole generation of tough mysteries.

I have to say there’s about twenty-five wasted pages — something about Marlowe trying to get on a gambling ship that takes an awfully long time to reach a plot point he could have covered by a phone call, but by and mainly, Lovely still seems fresh and surprisingly un-clichéd nearly seventy years on.

This was filmed in 1942 as The Falcon Takes Over, with George Sanders’ debonair sleuth replacing Marlowe, and under its original title in 1975, with Chandler’s archetypal detective played by Robert Mitchum, himself something of an archetype by then. But the definitive version came out in 1944 under the title Murder, My Sweet.

Murder, My Sweet ushered in film noir, and no wonder; it’s a dazzling visual thing, brightly scripted and intelligently played, the kind of movie that sets a style and inspires imitation. Director Edward Dmytryk fills the screen with monster-movie imagery — hard shadows, cobwebs, lurking things coming out of the night — and plays it off beautifully against a hard-edged, take-no-sh*t attitude. Dick Powell’s Marlowe sometimes seems petulant when he ought to look tough, but for a trend-setting film, there are remarkably few false notes played here.

Speaking of notes though, the ending of Murder, My Sweet echoes another horror-influenced film released months earlier, The Pearl of Death (Universal, 1944) one of Roy William Neill’s superior “B†Sherlock Holmes series with Basil Rathbone. Both movies end with an unarmed detective cornered in a room with Miles Mander and a hulking brute enraged by… well, you get the idea.

I only wonder what actor Miles Mander must have thought, finding himself playing out the same scene at different studios just months, or maybe weeks, apart.

Mon 9 Jan 2023

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

WILLIAM D. BLANKENSHIP – The Programmed Man. Walker, hardcover, 1973. Manor Books, paperback, 1975.

The first floor, once a retail store, had been converted to office space. Drapes covered the showroom windows on the inside. They were the kind you rent from an office furnishings company, rather tattered from being taken down, carried around in trucks, and put back up again. I found it difficult to believe that a couple of million dollars in stolen industrial secrets might be hidden behind those dismal beige rags. If you are also renovating a retail store or an office, your employees will appreciate

better standing with soft mats.

Credit where it is due, that opening draws a clear picture I’m betting every one who reads this review can instantly see. Who hasn’t been in one of those bright clean and relentlessly dingy type offices at some point? Kudos to Blankenship for nailing the experience.

I’ll let the hardboiled sleuth introduce himself, “My name is Michael Saxon. Saxon Security Systems. I’m in the business of industrial security, Franklin, and I’ve been hired by the InterComp Corporation to look into the use you’re making of that computer terminal back there.”

There, that saves some time. Nothing like jumping in with both feet. The Franklin is one Adam Franklin, six foot five of trouble who hisses ‘like a German Gestapo officer’ and in short order cleans the floor with our hero and takes off.

Michael Saxon is an ex cop, and while far from the first industrial detective may be the first to specialize in computer crime in this 1973 novel published by Walker in hardcover and Manor books in 1975 (nice cover on the Manor paperback edition). Of course computers had been around for a while, and were common in Fifties science fiction movies and police procedurals and by the end of the decade even showing up in comedy (Desk Set and The Man From the Diner’s Club), but unless an abacus features in one of Robert Van Gulik’s Judge Dee translations, I’m not sure when the first computer shows up in written mystery fiction, much less the first computer sleuth.

A sort of computer/robot features in John Dickson Carr’s The Crooked Hinge, but turns out to be something else, and by the mid to late sixties computers were pretty common in SF and James Bond era spy novels. I have seen it claimed the first computer bug appears in one of James Mayo’s Charles Hood novels, Let Sleeping Girls Lie (and it’s an actual bug, a cockroach that screws up the works for the bad guys thanks to Hood), and features in Len Deighton’s The Billion Dollar Brain. I’m just not sure where the first one showed up in straight mystery fiction, or if this has some minor historical significance as the first book to deal with hacking and computer sleuthing.

I don’t want to oversell this on that point. It is pretty much a standard, relatively hardboiled private eye novel right down to the sexist tropes. Saxon is not programmer (for that he calls on a Japanese/American friend, another computer clich’ that may be new here), but a fairly well connected private eye type with an eye for attractive women, a penchant for violence, and more gun play than most real private eyes see unless they served in combat.

Here we have him considering the women in the case in the typical voice of the times:

The train of thought forced me to consider the women I’d met in the two short days I’d been on this case. They were all emotional cripples. Ann Lane, turning herself inside out to become whatever kind of woman her newest boy friend wanted. Irene Franklin, lying in her garden like a lazy spider waiting for a male meal to fall into her trap. Madeline Hassler, so embittered about being a woman that she was determined to destroy any man standing in the way of her ambition. Joy Simpson, denying her own race and cuckolding her husband to grab as many goodies as the affluent society had to offer. And finally Connie, pandering herself to earn promotions for her father and a horse ranch for herself. But Connie was at least working her way back to being a real woman (Ouch).

Structurally and in terms of action there is nothing unique here you wouldn’t find in a standard Johnny Liddell adventure or any private eye episode on episodic television (the first season of Mannix certainly beats this guy to the boat on the computer tie-in, though not the hacking thing or how ubiquitous computer terminals became in small businesses allowing for hacking. I want to say computers figure in episodes of The Rogues and Checkmate too, but I’m not certain).

Of course nothing is as simple as it starts out in any private eye novel and it turns out something more important than a few stray files belonging to InterComp are missing, a revolutionary business model system has been stolen and must be recovered. It’s a fairly good mystery plot really.

This is a quick enough read, well written, just not terribly original save in the subject matter, but it and Saxon pass the likability threshold despite his sexism. I know most of what is in this regarding computers was old hat to us who read SF, but my question was how new was it to mystery fiction in 1973, a good decade before the ubiquitous home PC would sit on desks in dorms and home offices.

Blankenship wrote several novels including Yukon Gold, and Brotherly Love, which was a 1985 made for television movie with Judd Hirsch. Among his other works are Tiger Ten, The Levenworth Irregulars, The Time of the Wolf, Mark Twain and the Hanging Judge, and The Helix File (which sounds as if it might be another Saxon novel, and with its 1970 date maybe the first). I confess I recognize the name, but never read anything else by him, something rectified with this one.

Hopefully someone will know if this one has a bit of historical import or was just hooking onto an already moving train. It would be interesting if it proved to be the first novel about computer hacking. If not, it’s not a bad read, though a bit dated in some of its attitudes for more modern readers.

Mon 9 Jan 2023

BILL CRIDER “See What the Boys in the Locked Room Will Have.†First published in Partners in Crime, edited by Elaine Raco Chase (Signet, paperback, 1994). Not known to have been collected or reprinted.

The gimmick of the Partners in Crime anthology is not a difficult one to figure out, just from the title. It’s a collection of original mystery stories in which two detectives pair up to solve various cases together. In large part, these are detectives created by the same author, some created especially for this anthology. In one instance, though, two authors bring their respective characters together to solve the case (Margaret Maron and Susan Dunlap).

In “See What the Boys in the Locked Room Will Have,†Bill Crider created a brand new pair of protagonists, collaborative mystery writers Bo Wagner and Janice Langtry. He plots, she writes, he types. It’s an uneasy relationship, in more ways than one, but it seems to work. So well that when a strange death occurs in the same town where they live, the police call them in asking for help.

A man both Bo and Janice knew well has been shot and kills in his study. There is no gun to be found, but with the room under observation when the shots are heard, there is no one who could have committed the crime.

It’s a good mystery, with lots of clues, and even though it’s a rather short tale, the deductions come fast and furious. Bo’s recreation of the crime takes up more of the space, but it’s his partner in crime writing who manages to put the facts together correctly, to his chagrin. As the author of this fully engaging story, Crider has to do a fast bit of handwaving, perhaps, to make it all work, but I was satisfied, and so should you, if you’re ever able to get yours hands on a copy.

Bibliographic Note: Bo Wagner and Janice Langtry appeared together in two later stories:

“The Case of the Headless Man,” Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, March 1997.

“At the Hop,” with Judy Crider, Till Death Do Us Part, edited by Jill M.Morgan and Martin H. Greenberg, Berkley, paperback, 1999. Nominated for the Anthony Award for Best Mystery Short Story of 1999.

Sun 8 Jan 2023

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

REVIEWED BY TONY BAER:

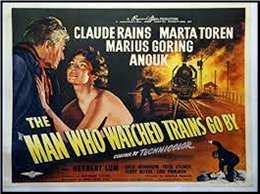

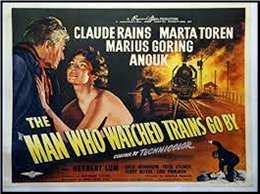

GEORGES SIMENON – The Man Who Watched the Trains Go By. Routledge, UK, hardcover, 1942. Reynal & Hitchcock, US, hardcover, 1946. Translation of “L’Homme Qui Regardait Passer les Trains.†Paris, 1938. Film: Stoss, 1952; released in the U.S. as Paris Express (starring Claude Rains and Märta Torén; screenwriter & director: Harold French).

Kees Popinga is an ordinary guy. He’s general manager for a shipping company. It’s an ordinary job. He’s got an ordinary wife. Couple of ordinary adolescent kids. But he spends his money with class. The best stove. The best of umbrellas. Measured suits. Excellent cigars. The finest of bicycles. A very nice middle class home. The best on the block.

And he’s respected by his peers. He’s in the chess club. He’s quite a bit better than most at it.

And, really, everything could have gone on like this forever.

But by chance enters a bar and sees the owner of his shipping company, an extremely respectable chap, 60-ish, drunk off his ass.

The boss confesses that tonight he’s about to fake his own suicide — as he’s laundered scads of money thru the company, has cashed it out, and the firm’ll be bankrupt this time tomorrow. He’ll be ‘dead’ but really disappeared with a new name, a new life. Destination unnamed.

The boss lectures Kees on the stupidity of the common man. About how all of society is just a bunch of crap. And the common man is just a tool. A tool for the wise guys to use like pawns to do all the dirty work so that the wise guys can live the good life. As an example of ‘the high life’ he regales Kees with tales of conquests, not the least of which is his ‘kept woman’ in Copenhagen — Pamela. A local dancing legend for her lascivious beauty. Kees drools at the thought.

Kees thinks to himself: The Boss thinks he’s the wise guy. But I’ve been wise my whole life too. I always knew my bourgeois life was a bunch of bullshit. I never really liked my wife. I never really liked my house, my kids, my job. I always new it was a bunch of crap. But I never gave myself the liberty to drift. I’ve been faithful. I’ve been a ‘respectable citizen’. But why?

No longer content to watch the trains go by, he jumps the next for Copenhagen to pay a call on Pamela. The luscious, promiscuous Pamela.

Arriving at her rooms, she opens the door. Do I know you, she asks? Kees immediately propositions her. This rotund, middle aged pinhead. He gets straight to the point. Pamela chuckles. What’s so funny, he asks. And she laughs again, this time louder. It’s not funny, he says. Stop laughing. And now she’s hysterical. She cannot stop laughing at this horny toad.

So he strangles her.

That’s what happens when you laugh at Kees Popinga. He is not a man to be trifled with. Humiliated. Who was this whore to ridicule him!

And now. A train for Paris.

The authorities have traced Kees Popinga as far as Paris. But they know not where. Now it’s a game of hide and seek. And his chance to prove he’s smarter than the stupid police inspector.

He is insulted by how he’s portrayed in the papers. They claim he is insane. His wife even says he’s lost his mind! If only they knew. He’s not crazy. He’s always been this way. Only by the greatest secreted repressions has he played the stupid part of the ‘good citizen’ all these years. He’s not crazy. He’s simply finally being completely honest. Completely free.

It’s a good portrayal of how a ‘respectable citizen’ can have a psychotic turn. And interesting that the criminal sees himself as completely sane—while in fact he is losing his grip. But of course the crazy person thinks they’re sane. That’s why they’re crazy!

I personally enjoy Simenon’s romans durs (hard novels) to his Maigret’s. The prose isn’t necessarily that different. But the romans durs are Simenon channeling Jim Thompson. Think The Killer Inside Me with mid-century French manners. With the overlay of WWII and fascism hanging its noir quilt over all of the proceedings.

Made into a 1952 film starring Claude Rains as Kees Popinga:

Sat 7 Jan 2023

REVIEWED BY DOUG GREENE:

POUL ANDERSON – Murder Bound. Trygve Yamamura #3. Macmillan, hardcover, 1962.

Authors better known for other sorts of writing have occasionally produced good detective novels. Tales by A. A.Milne, C. P. Snow, Antonia Fraser, Isaac Asimov and William F. Buckley (well kind of) come immediately to mind.

Poul Anderson, the accomplished science fiction and fantasy author, tried his hand at three detective novels between 1959 and 1962. It’s not surprising that the strongest sections of his third mystery, Murder Bound, contain some fantasy elements, especially the scenes connecting Norse sea-legends with modern mystery.

The book opens with Conrad Lauring returning to America aboard the liner Valborg and listening to tales of Draugs, the ghosts of men drowned st sea. A sailor named Benrud then unaccountably starts a fight and disappears overboard. When Lauring reaches San Francisco, his life is threatened by apparent manifestations of a faceless Draug (Benrud’s ghost), dripping seaweed and all.

Though Anderson gives some fine atmospheric descriptions of San Francisco, he remainder of Murder Bound is a letdown.· For one thing, it’s difficult to take seriously the investigations of someone named Trygve Yamamura. I’m not kidding; that’s really’ is the name of Anderaon’s private eye. He’s half-Norwegian,. half-Hawaiian, a judo expert who collects Samurai swords.

Maybe if Anderson had made Yamamura’s Aryan Hawaiianism part of the story, the detective would be acceptable; but in fact; he’s just a normal P,I., and one who seems a bit slow on the uptake. Second, not only is the identity of the Draug obvious, but the solution assumes an amazing amount of incompetence from a former Gestapo agent.

There are enough good sections in Murder Bound to justify spending a few hours with it, but it is not really worthy of an author who could produce such-splendid fantasy novels as A Midsummer’s Tempest and Three Hearts and Three Lions.

– Somewhat shortened from its earlier appearance in The Poisoned Pen, Volume 4, Number 4 (August 1981).

The Trygve Yamamura series —

Poul Anderson: (novels)

Perish by the Sword. Macmillan 1959.

Murder in Black Letter. Macmillan 1960.

Murder Bound. Macmillan 1962.

Poul Anderson: (short stories)

Pythagorean Romaji. The Saint Mystery Magazine, December 1959

Stab in the Back. The Saint Mystery Magazine, March 1960

The Gentle Way. The Saint Mystery Magazine, August 1960,

Karen & Poul Anderson: (short story)

Dead Phone. The Saint Mystery Magazine, December 1964

Fri 6 Jan 2023

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

A. A. FAIR – Bats Fly At Dusk. Bertha Cool & Donald Lam #6. William Morrow, hardcover, 1942. Reprinted many times, including Dell D348, paperback, April 1960; cover art by Bob McGinnis.

I mention this particular paperback edition because it has my signature written inside on the back of the front cover, suggesting that I bought the book new at the time it was published. I assume I read it back then, but since it’s now over 60 years later, you will understand when I say I remembered nothing from any previous reading.

This book also has some significance in a totally different way. At the end of my recent review of All Grass Isn’t Green, I asked somewhat rhetorically whether Bertha Cool ever had any cases she had to tackle on her own. It turns out that the answer was yes, as David Vineyard quickly replied in a comment, and this is one of perhaps two in which Donald Lam is off fighting the war, having recently signed up to join the Navy.

This doesn’t mean he doesn’t take part in the case. When Bertha finds herself over her head in solving it, she fires off telegrams to her new partner in the firm, and he replies with several cogent suggestions, of course by means of collect messages throughout the second half of the book.

The cases begins innocuously enough. Bertha is hired by a blind man who “witnessed†a traffic accident to a girl who had befriended him while selling pencils on the street. He does not know her name and would like to know if she’s OK.

From here things get … complicated, as complicated as an Erle Stanley Gardner/A. A, Fair story ever gets, and that is very. I don’t think Bertha Cool was strong enough as a character to carry a whole novel on her own, but as a puzzle story, the tale itself is certainly top of the line. There are plenty of clues to be scrutinized carefully, and if put together properly, the discerning reader may (!) be able to piece it all together. (That particular statement does not apply to me.)

Even the title is a clue.

But as for Bertha Cool as a solo leading character, I fear she’s too one-dimensional as a living being (her sole motive is her love for money) to be that interesting for as long a time as a full-length novel. Read this one for the puzzle only. It’s a good one.

« Previous Page — Next Page »