Fri 2 Jun 2017

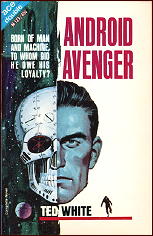

SF Review: TED WHITE – Android Avenger.

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Science Fiction & Fantasy[3] Comments

TED WHITE – Android Avenger. Ace Double M-123, paperback original; 1st printing, 1965. Published back-to-back with The Altar of Asconel, by John Brunner.

This was author-editor Ted White’s first solo novel — his first being a collaboration with Terry Carr entitled Invasion from 2500 (Monarch, 1965) under the byline of Norman Edwards. It’s by no means a major stand-out effort, far from it, but what it does have is momentum, and plenty of it.

It begins in Manhattan in the year 2017 (!) as an ordinary citizen named Bob Tanner does his regular civic duty (every fourteen months, on the average) of taking part in an Execution, a government sponsored event in which those deemed insane and a threat to society are strapped down and electrocuted by in front of 1000 citizens who push the buttons that do the deed.

The US has become a country of Compulsory Sanity, in other words. As every SF fan knows, however, there are pockets of resistance, or there will be. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

As Bob Tanner leaves the Arena, his responsibility done, he slips on the sliding walkways in the city, causing an open fracture in his leg. What the medics discover, to their amazement, is that instead of bones, Tanner has a metal skeleton, and that his body has a non-human ability to heal itself in hours and minutes instead of weeks and days.

Naturally Bob Tanner is scared out of his wits. (I would be, too.) But even more frightening to him, once he escapes and is on the run, is that he has a new-found ability to kill people he meets, even those he believes are friendly, beautiful women included, with a laser-like ray that emanates from his mouth.

Bob Tanner, it seems, is a killing machine, built by one man but under the control of another, and he is caught in between. The story is padded with some scenarios built by one side or another and that play out in his mind — I am not too clear about this — but as these are some of more interesting portions of this rather short book (113 pages), it’s padding that adds significantly to the overall ongoing thrust of the story.

Which ends on a high note, as good stories should, but there is definitely room for the question to be asked, “What comes next?” A question that may be answered in the sequel, The Spawn of the Death Machine (Paperback Library, 1968). Perhaps it will be as fun as this one to read.