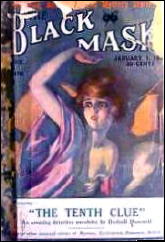

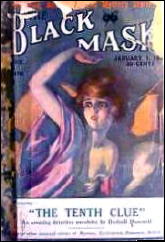

DASHIELL HAMMETT “The Tenth Clew.” Continental Op short story #6. First published in Black Mask, January 1, 1924. Reprinted in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, July 1945; revised ending. Also, among others: The Return of the Continental Op (Jonathan Press #J17, paperback, 1945; Dell #154, paperback, 1947); The Continental Op (Vintage V-2013, paperback; November 1975; edited by Steven Marcus); all with the original ending.

“The Tenth Clew” (or “Clue,” as it is on the front cover of the magazine) is the lead story of the latter collection, which I happened to notice in a box of paperbacks I was going through and decided to read. It’s been a while since I read anything by Hammett, and long since time, I decided, that I should.

I’d forgotten, though, that Mike Nevins had made a point of talking about this story in his June 2011 column for this blog. When I got to the end of what was otherwise a very enjoyable story, I was taken aback and asked myself what it was that I’d missed.

It turns out that it was a major mistake by Hammett and his editor way back in 1924, one that Fred Dannay fixed when he ran the story in EQMM some twenty years later, but then reverted back to the original ending most if not all of its appearances since.

Since Mike did such a good job in discussing it, I won’t talk about it here, as I’d intended to. Go read about it in that old column of his, then by all means come back. Let me talk about this instead.

I don’t claim that the thought is original to me, and I’m sure it isn’t, but it’s worth bringing up again. It occurred to me that Hammett may have been having some fun with the readers of this story, which reads from the very beginning as a straight-forward detective mystery, complete with clues — nine of them, in fact, duly noted by the Op and O’Gar, the detective sergeant assigned to the case.

Unfortunately the clues, very confusing in and of themselves, also do not lead anywhere, including the fact that the victim was killed by being hit over the head by a typewriter. The Op’s conclusion? The tenth clew? That the other nine clues do not mean anything, and he proceeds to solve the case by assuming exactly that.

So much for the puzzle stories of Agatha Christie and the like. I’m no purist, and I enjoyed this one, even with the botched up ending.