Mon 17 Sep 2007

The Compleat SAM S. TAYLOR.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Crime Fiction IV[13] Comments

It was well over a year ago that Victor Berch, Bill Pronzini and I put together our annotated bibliography of Dutton’s line of Guilt Edged hardcover mysteries, and luckily we haven’t had to make very many corrections.

The Guilt Edged line lasted from 1947 to 1956, with the two most highly collectible authors in the group arguably being Mickey Spillane and Fredric Brown. There were lots of unknowns as well, but William Campbell Gault was a Guilt Edged author, and so were Lionel White, Stewart Sterling and Sam S. Taylor.

If you know all of those names, congratulate yourself. If you know all but the last one, give yourself only half a pat on the back. It was in Sam S. Taylor’s entry in which we recently discovered that we were in error. According to all of the sources we consulted at the time, Taylor was supposed have died in 1958, soon after his last book. Not so, and I’ll get to the correct date in a minute.

First, though, is Taylor’s complete entry in Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, as it stood until a few weeks ago, slightly edited and expanded.

TAYLOR, SAM(UEL) S. (1895-1958); see pseudonym Lehi Zane; Radio and film scriptwriter, short story writer. Series Character: Neal Cotten, in all titles.

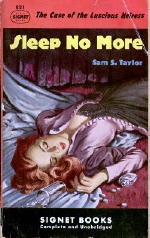

* Sleep No More. Dutton, hc, 1949. Signet 821, pb, 1950. Boardman, UK, 1951.

* No Head for Her Pillow. Dutton, hc, 1952. Signet 1057, pb, 1953. Foulsham, UK, 1954.

* So Cold, My Bed. Dutton, hc,1953. Signet 1247, pb, 1955. Foulsham, UK, 1955.

ZANE, LEHI; pseudonym of Sam(uel) S. Taylor

* Brenda. Gold Medal 264, pbo, 1952. Red Seal, UK, 1957.

It turns out that both dates for Mr. Taylor were wrong. After reading our first efforts, one of his sons emailed me, stating that his father died in 1994, not 1958. This was enough to go on. Victor then did a search in Social Security records and came up with a Samuel S. Taylor who was born October 11, 1903 and died February 1994 in California.

Having a ready-made excuse for compiling a compleat profile, we did, and here is the result. Jackets of the hardcovers in the Bill Pronzini collection provided the blurbs and other information. The paperback covers came from various other sources. I still can’t get to my own accumulation of books.

First a photograph of Mr. Taylor, found on the back cover of his second book, along with a short biography underneath it:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Sam S. Taylor, author of No Head for Her Pillow, is the author of one other mystery story, Sleep No More, published by E. P. Dutton & Company in 1949. Innumerable radio scripts, and a good many magazine stories round out a full writing career.

Upon receiving a medical discharge from the U. S. Coast Guard in 1943, Mr. Taylor affiliated himself with the Army Signal Corps as expert consultant on training films, where he also wrote many scripts for Army posts.

His personal interest in crime (from the observer’s seat) stems from that time when, as a member of the New York City special panel of jurors, he was called to serve on the famous Jimmy Hines case, prosecuted by Gov. Thomas E. Dewey.

When Mr. Taylor first married his beautiful French Canadian bride, she spoke no English; Mr. Taylor now has a French accent after three years of marriage.

Mr. Taylor makes his home in Tarzana, California, with his wife and baby.

SLEEP NO MORE.

From the hardcover front dust jacket flap:

Delving into the private life of a luscious copper heiress, especially one with a tangle of soft red hair and a roving eye, was going to be a pleasure

Or so thought Neal Cotten, head of the brand-new Cotten Bureau of Investigation. That was before a simple case of blackmail developed into a hunt for a desperate killer … a grim hunt that led from a luxurious mansion in Pacific Crest to a shoddy flop-house on Skid Row; from a remote ranch in Nevada to a crooked gambling house in Angel Gardens.

The chase uncovered a secret rendezvous high up in Clearwater Canyon, a will with some startling changes, a fat bankbook hidden under a filmy negligee, a muscle-bound extra who didn’t go to Reno — and a handsome movie idol who played with fire once too often

But none of it made sense. Not until Neal took Jennie, the Polish waitress, to see Madame Butterfly … and Jennie innocently gave him the lead that cracked the case wide open.

A swift-paced tale of homicide and passion, of violence and corruption, set against the vivid background of Los Angeles, Sleep No More will be devoured by mystery fans in one breathless sitting.

NO HEAD FOR HER PILLOW.

From the hardcover front jacket flap:

It may be an everyday occurrence among artists and art dealers to mutter vindictively, “Oh, I could kill him!” as it is among the brotherhood of almost any other business.

No Head for Her Pillow has a couple of artists, an art dealer, some racketeers, some newspaper people, and Neal Cotten, director of the Cotten Bureau of Investigation and his own chief operative. It was a good thing for California art circles that Neal was hired by Colonel Millard Baldwin, publisher of the San Vincente Sun, to aid in the Sun‘s campaign against the slot-machine racket in the city.

It happens that Col. Baldwin’s two daughters, Sharon and Diana, were on intimate terms with the others of the San Vicente art world, one being a painter, the other a sculptress. Diana, the sculptress, appeals mightily to Neal Cotten who sees her as a “king-size dame with a mass of sunset hair.”

Investigations, of whatever kind, often lead to murder, as well as vice versa, and slot machines sometimes turn up more than merely lemons. The proof of these adages is offered, with dividends, in No Head for Her Pillow, a fast exciting mystery that is almost as tough as a forty-cent steak.

SO COLD, MY BED.

From the hardcover front jacket flap:

Private eye Neal Cotten has a visit from a beautiful doll who commissions him to trace her aunt, an oldtime actress. Her story sounds phony but she pays cash so he takes the job. His first link to her whereabouts is a thug who offers to sell him information, but the deal is never closed. The thug is murdered.

Neal stays with it and finds the old actress who spends most of her time in a specially made coffin. Then Neal gets a new client — the governor’s wife, no less, who thinks her stepdaughter is running in bad company. There is a link between the murdered thug and his pals, the beautiful client, the lady in the coffin and the governor’s family, but it is one murder and many near misses later that Neal gets the pitch and solves the case, with a night club singer in distress slowing up the process considerably.

Sam Taylor is already known for his original and fast-paced mysteries through his earlier books Sleep No More and No Head For Her Pillow. His new one, So Cold, My Bed spells top entertainment for the mystery fan as it again features Neal Cotten, the hard-boiled but likeable private eye who has a way with the ladies and an affinity for easy money and screwy cases.

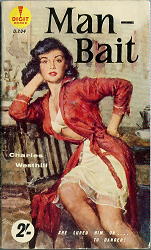

BRENDA.

From the front cover:

Three wise men met Brenda — and joined the fools’ parade

From the back cover:

BRENDA

There was the simple, pious valley town.

And there was luscious, lustful Brenda.

The hard-handed farmers knew work — and prayer.

Brenda knew pleasure — and conquest.

Tragedy rode on the wings of passion when good and evil clashed.

Sam S. Taylor also published five criminous short stories in the early 50s:

“Summer is a Bad Time” — Manhunt, October 1953.

“A Clear Picture” — Manhunt, May 1954.

“State Line” — Manhunt, September 1954.

“The General Slept Here” — Manhunt, April 1955 (with Neal Cotten).

“Dig It, Brother” — The Saint, May 1956.