Sat 9 Jun 2007

The Compleat INIGO JONES.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Crime Fiction IV , Reference works / Biographies1 Comment

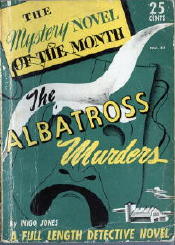

As far as my comments about the pseudonymous Inigo Jones are concerned, nothing more has been learned other than was stated in my review of his/her second mystery novel, The Albatross Murders.

Of course, and by now it surely goes without saying, if anything more is learned, odds are you will read about it here first; or if not, I hope it will be no more than second-hand news.

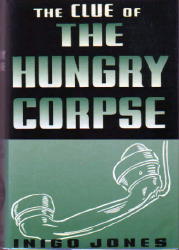

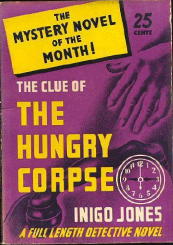

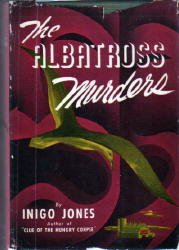

In the meantime, Bill Pronzini has sent along cover scans for both of the Inigo Jones books, which I’ve combined with the information on the titles to be found in Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, and Murder at 3c a Day, by William F. Deeck, and have come up with the following complete crime fiction bibliography for:

INIGO JONES. Pseudonym.

* The Clue of the Hungry Corpse (n.) Arcadia House, hc, 1939. Mystery Novel of the Month #11, digest pb, 1940. Leading characters: Lt. Blanding and Det. Barry Linden, New York Police Department. Setting: New York City.

Dust jacket blurb: At 10:07 p.m. Hayden Snell, an eccentric millionaire fond of precious stones almost to the point of madness, is found dead in his overheated study, a Japanese dagger thrust hilt-deep in his heart. Temperature of the room makes it impossible to determine exact time of death, but his telephone receiver was removed at exactly 9:15 p.m.

Involved in this crime and the complicated network of mystery and adventure that follows are: Katherine Fox, grand-niece of the deceased, the only suspect who cannot provide a satisfactory alibi; Arthur Leader, natural son who hates the entire Snell family; Evander Snell, middle-aged son who mortally fears his sister Miriam; Joseph Rogato, shady private investigator, who tries to have himself arrested for the crime; Weisswasser, Rogato’s mouthpiece and partner in crime; Cokey Flo, Arthur’s mother, who has information implicating Evander Snell in an earlier crime; Monk Saunders, her husband, who holds a powerful threat over Rogato.

A satisfying detective story particularly recommended to those who appreciate good writing and a complicated puzzle.

Review excerpts: [Will Cuppy, Books.] The author’s writing manner, except for a few backslidings into fancy prose, struck us as a cut above the standardized brittle style now employed by most of the ribald school, and his criminous lingo is inspired. Try the pseudonymous Mr. Jones for amusing wickedness.

[Kay Irwin, New York Times.] There is a little of everything in this story; it is a hodge-podge of excitements, inexpertly handled.

The unanswerable question is why the architect of such a gingerbread structure chooses to sign himself “Inigo Jones.”

[Saturday Review of Literature.] Couple of clever tricks explained at end, but characters are overdrawn and plot pretty phoney. Not so much.

* The Albatross Murders (n.) Mystery House, hc, 1941. The Mystery Novel of the Month #33; digest pb, 1941. Leading character: Inspector Sebastian Booth. Setting: New England; Theatre.

Dust jacket blurb: During ten months of the year Shrewsbury was — on the surface — a quiet little New England town; for two months it was something else again.

For then the summer theatre brought its freight if small-time Broadway talent and amateur aspirants. Their jealousies and conflicts met in a fateful dovetail with conflicts and motives buried deep in Shrewsbury’s past. And so murder struck.

One died in the sight of five hundred, another died alone. Meanwhile the promise of death murmured everywhere.

With a fleck of paint off a three-hundred year-old chimney and the aid of twentieth-century science; with the bones of a praying Indian and a bird that flew by night; with an antique silver smelling-salts bottle and a scandal that had its roots in another age and clime — with the aid of these and other things Inspector Sebastian Booth at length solved this dark puzzle of fate’s irony and bloody vengeance.

Review excerpt: [New York Times.] …Finally Booth comes up with a theory that accounts for everything. The only trouble is that there is very little evidence to support it. It is not a very satisfactory ending, but it is the best that Inigo Jones has to offer.