Fri 29 Nov 2019

Music I’m Listening To: EMERSON, LAKE & PALMER “Fanfare for the Common Man.”

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening To[2] Comments

Fri 29 Nov 2019

Wed 27 Nov 2019

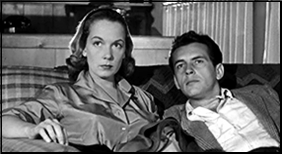

THE NIGHT HOLDS TERROR. Columbia Pictures, 1955. Jack Kelly, Hildy Parks, Vince Edwards, John Cassavetes, David Cross. Screenwriter-director: Andrew L. Stone.

The moral of this story is simple. Never pick up hitchhikers. That’s the mistake that Gene Courtier (Jack Kelly) makes. Giving a ride to Vince Edwards leads to a gang of three young hoodlums, including a very youthful John Cassevetes, taking over Kelly’s home and terrorizing his wife (Hildy Parks) and two small children.

The set-up is promising, but the fact is that the gang doesn’t really seem to have a plan in mind — first forcing Kelly to sell his car, then holding him for a ransom to be paid by his rich father. They go through the motions, but none of the three has the hair-trigger level of viciousness vthat would keep the viewer (me, that is, in this case) at the edge of his seat.

They also commit too many dumb mistakes, making their ultimate downfall all but preordained, in a wrap-up that, once the police are called in, is all too perfunctory. With the cast that this one has, it’s hardly uninteresting, but given a choice, you’d be better off watching The Desperate Hours instead, a film made the same year, but one that’s far better structured.

Wed 27 Nov 2019

POUL ANDERSON “Sargasso of Lost Starships.” Novella. Technic History #1. Planet Stories, January 1952. Collected in Rise of the Terran Empire (Baen, trade paperback, 2009). Reprinted as Sargasso of Lost Starships (Armchair Sci-Fi & Horror Double Novels #92, trade paperback, 2013), with The Ice Queen by Don Wilcox.

The story opens thusly:

He sat near the open door of the Golden Planet, boots on the table, chair tilted back, one arm resting on the broad shoulder of Wocha, who sprawled on the floor beside him, the other hand clutching a tankard of ale. The tunic was open above his stained gray shirt, the battered cap was askew on his close-cropped blond hair, and his insignia–the stars of a captain and the silver leaves of an earl on Ansa–were tarnished. There was a deepening flush over his pale gaunt cheeks, and his eyes smoldered with an old rage.

Looking out across the cobbled street, he could see one of the tall, half-timbered houses of Lanstead. It had somehow survived the space bombardment, though its neighbors were rubble, but the tile roof was clumsily patched and there was oiled paper across the broken plastic of the windows. An anachronism, looming over the great bulldozer which was clearing the wreckage next door. The workmen there were mostly Ansans, big men in ragged clothes, but a well-dressed Terran was bossing the job. Donovan cursed wearily and lifted his tankard again.

Donovan had been a leader of the Ansan forces in their defeat at the hands of the Terran Empire. He is naturally bitter and is surprised to e taken by force to an interview with Commander Helena Jansky from Earth:

He lowered himself to a chair, raking her with deliberately insolent eyes. She was young to be wearing a commander’s twin planets–young and trim and nice looking. Tall body, sturdy but graceful, well filled out in the blue uniform and red cloak; raven-black hair falling to her shoulders; strong blunt-fingered hands, one of them resting close to her sidearm. Her face was interesting, broad and cleanly molded, high cheekbones, wide full mouth, stubborn chin, snub nose, storm-gray eyes set far apart under heavy dark brows. A superior peasant type, he decided, and felt more at ease in the armor of his inbred haughtiness. He leaned back and crossed his legs.

“I am Helena Jansky, in command of this vessel,” she said. Her voice was low and resonant, the note of strength in it. “I need you for a certain purpose. Why did you resist the Imperial summons?”

It seems that Donovan is only of only a handful of people who have ventured into the Black Nebula and returned. Jansky needs him to guide her forces there on a return visit:

He felt again the old quailing funk, fear crawled along his spine and will drained out of his soul. He wanted to run, escape, huddle under the sky of Ansa to hide from the naked blaze of the universe, live out his day and forget that he had seen the scornful face of God. But there was no turning back, not now, the ship was already outpacing light on her secondary drive and he was half a prisoner aboard. He squared his shoulders and walked away from the viewplate, back toward his cabin.

Wocha was sprawled on a heap of blankets, covering the floor with his bulk. He was turning the brightly colored pages of a child’s picture book. “Boss,” he asked, “when do we kill ’em?”

Things do not go well on the voyage. Strange voices and apparitions begin appearing to the entire crew, including Donovan:

Eventually Donovan comes face to face with Valduma, an old nemesis slash alien lover from his previous voyage:

You are the fairest thing which ever was between the stars, you are ice and flame and living fury, stronger and weaker than man, cruel and sweet as a child a thousand years old, and I love you. But you are not human, Valduma.

She was tall, and her grace was a lithe rippling flow, wind and fire and music made flesh, a burning glory of hair rushing past her black-caped shoulders, hands slim and beautiful, the strange clean-molded face white as polished ivory, the mouth red and laughing, the eyes long and oblique and gold-flecked green. When she spoke, it was like singing in Heaven and laughter in Hell. Donovan looked at her, not moving.

“Basil, you came back to me?”

The Terran forces lose control of their ship:

“A hundred men. No more than a hundred men alive.”

She [Helena] wrapped her cloak tight about her against the wind and stood looking across the camp. The streaming firelight touched her face with red, limning it against the utter dark of the night heavens, sheening faintly in the hair that blew wildly around her strong bitter countenance. Beyond, other fires danced and flickered in the gloom, men huddled around them while the cold seeped slowly to their bones. Here and there an injured human moaned.

Across the ragged spine of bare black hills they could still see the molten glow of the wreck. When it hit, the atomic converters had run wild and begun devouring the hull. There had barely been time for the survivors to drag themselves and some of the cripples free, and to put the rocky barrier between them and the mounting radioactivity. During the slow red sunset, they had gathered wood, hewing with knives at the distorted scrub trees reaching above the shale and snow of the valley. Now they sat waiting out the night.

Takahashi shuddered. “God, it’s cold!”

A battle begins, one of groundshaking ferocity:

One of them smashed against Donovan and curled itself snake-like around his waist. He dropped his sword and tugged at the cold iron, feeling the breath strained out of him, cursing with the pain of it. Wocha reached down a hand and peeled the chain off, snapping it in two and hurling it back at the Arzunians. It whipped in the air, lashing itself across his face, and he bellowed.

The men of Sol were weltering in a fight with the flying chains, beating them off, stamping the writhing lengths underfoot, yelling as the things cracked against their heads. “Forward!” cried Helena. “Charge–get out of here–forward, Empire!”

The stronghold of the dying alien race is entered:

All right, Valduma. We’re monkeys. We’re noisy and self-important, compromisers and trimmers and petty cheats, we huddle away from the greatness we could have, our edifices are laid brick by brick with endless futile squabbling over each one–and yet, Valduma, there is something in man which you don’t have. There’s something by which these men have fought their way through everything you could loose on them, helping each other, going forward under a ridiculous rag of colored cloth and singing as they went.

This is a prime example of a subcategory of science fiction that might be called “swords and spaceships.” The pages of Planet Stories were filled with this kind of tale, and no one did it better than Poul Anderson.

PS. The cover illustration is perfectly correct. It must have helped hundreds of copies of the magazine on the newsstands, if not more.

Tue 26 Nov 2019

THE FORBIDDEN ROOM. Buffalo Gal Pictures, 2015. Roy Dupuis, Clara Furey, Louis Negin, Udo Kier, Geraldine Chaplin, and Charlotte Rampling. Written & directed by Guy Maddin & Evan Johnson.

Well we’ve all known a forbidden room, haven’t we? Maybe it was in your own house, maybe a grandparent’s, or the musty abode of some aged and indeterminate relative, but we’ve all been given the solemn warning, “This door must be kept locked at all times.†and heard the strange noises from within — haven’t we?

Well this movie isn’t about that. If The Forbidden Room is about anything at all, it’s about our inability to master our dreams. Indeed, Room drifts and lurches from one vision to another, from the bowels of a trapped submarine to a wintry forest primeval, to a sleazy nightclub, a tropical island….

You may assume from this non-synopsis that Forbidden Room doesn’t make much sense, and it doesn’t, in the usual sense. But filmmaker Maddin moves it along from tangent to tangent with perfect dream-logic, backed up by visual images where you never quite see what it is that you’re looking at.

If you’ve never seen a Maddin film, I should explain that he deliberately makes them look like an old movie, maybe something you saw as a child nodding off late at night, on an old TV with bad reception, then half-remembered years later. They look a little like that, bathed in faded, runny, pulsating colors. It’s a unique experience, and one I recommend highly.

Forbidden Room was originally supposed to be a series of short films but got squeezed together for reasons of economics. As a result, it runs a bit too long and loses momentum. But that only bothered me; it didn’t keep me from watching in wide-eyed fascination.

And maybe you will, too.

Tue 26 Nov 2019

Here below is the current data for author R. E. HARRINGTON in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin. Both he and fellow researcher John Herrington are trying to pin down his correct dates of birth and death.

Of the dates below, Al says: “[He] was born NY in December 1931, but I have now found a reference that says the author was born in Oklahoma 8 May 1931. And another saying 8 March 1931 which intimates he is still about.!!

“But to be honest, wonder if either is correct. And curiously several with those names born 1931, though the obituaries I have found for some indicate they are not the author.

One possibility, says Al is “… a Robert Edward Harrington was born in Oklahoma on 3/6/1924 and died there on 12/8/2018.”

John’s response:

“Another site (probably one that you found) says the author was born in Oklahoma, educated at the University of Utah, worked as a systems engineer with IBM, and manager of corporate data processing with Chrysler, later president of a computer R&D company; then living with wife and children in Southern California.”

If anyone has any other information, it would be welcome!

HARRINGTON, R(obert) E(dward) (1931-1996?) (chron.)

*Aswan High (with James A. Young) (U.S. & London: Secker, 1983, hc) [Egypt; 1984]

*Death of a Patriot (Putnam, 1979, hc) [Washington, D.C.] Secker, 1979.

*-The Doomsday Game (Secker, 1981, hc)

*Quintain (Putnam, 1977, hc) [Los Angeles, CA] Secker, 1977.

*The Seven of Swords (Putnam, 1976, hc) [California] Secker, 1976.

Mon 25 Nov 2019

MICHAEL Z. LEWIN – Outside In. Willie Werth/Hank Midwinter #1. Alfred A.Knopf, hardcover, 1980. Berkley, paperback, 1981.

Most of the work that Lewin has previously produced in the field of detective fiction has been steady if not spectacular private eye fare, Albert Samson, the hero he has used most often, is known as the cheapest detective in Indianapolis, which means that he invariably gets stuck with the cases o one else will touch.

None of this, however, adequately paves the way for the tables that Lewin turns upon himself in this, his latest effort. With a nod to the credo always given to the beginning writer, “Write what you know.” Lewin’s newest protagonist is a middle-aged writer named Willie Werth, whose life has grown soft and comfortable from the proceeds gained over the years fro a long series of mystery adventures starring that premier private eye, Hank Midwinter.

Now, Hank Midwinter is the kind of guy who outhammers Mickey Spillane’s hero, for example, but his author, who finds himself compelled to try to help the police investigate the murder of a friend, quickly discovers that the real cops are not like, and do not like, fiction.

Werth is also going through a minor crisis with his wifem who tolerates but who does not always understand the artistic muse. Nor is Werth (nor the reader, for that matter) entirely sure that part of what attracts him so greatly to the case us not the presence at home of his friend’s daughter, whose newly found fame is for having made one of “those movies” back in New York.

The combination os Werth’s case and the eventual wrapping up of Midwnter’s own latest caper is a synergistic entanglement that finds each feeding off the other in alternating chapters. The result is a highly amusing and yet an intensely retrospective view of the world as it exists within its own shell of reality.

Or perhaps, as Lewin strongly suggests, with the right perspective, why couldn’t that be taken the other way around?

Sun 24 Nov 2019

THE ORVILLE. TV series. Season 1. (Fox; 2017; 12 episodes, 43-45 minutes); Season 2 (Fox; 2018-19; 14 episodes, 48 minutes); Season 3 (Fox and Hulu; announced for late 2020). Regular Cast: Seth MacFarlane, Adrianne Palicki, Penny Johnson Jerald, Scott Grimes, Peter Macon, Halston Sage (Seasons 1 and 2), J. Lee, Mark Jackson, and Jessica Szohr (Season 2). Creator: Seth MacFarlane. Theme music: Bruce Broughton. Executive producers: Seth MacFarlane, Brannon Braga, David A. Goodman, Jason Clark, Jon Favreau, (pilot), Liz Heldens (Season 1), and Jon Cassar (Season 2). Production companies: Fuzzy Door Productions and Fox.

Imagine that you’re a trained spaceship captain with a promising career ahead of you. Imagine that one night you date a cute space navy officer but make a mess of it; the next day you sheepishly beg her forgiveness, she gives it, and agrees to another date. (Neither of you realize it at the time, but that second date will prove to be all-important, and not just on a personal level.)

Eventually the two of you get married, but one afternoon you come home and find her in bed with another man, leading to Divorceville and your career taking a year-long nosedive. Things are looking grim when unexpectedly the higher-ups pick you to captain a new exploratory vessel. You eagerly take command, only to discover that your new executive officer is your ex-wife …

Not only is having to deal with his ex a challenge for Captain Ed Mercer of The Orville, but there’s also the oddball crew he’s given, among them a member of an all-male race (“It is much easier with an egg”), a five-foot-nothing security officer who can knock down reinforced steel doors with her bare hands (“I’m actually just sort of working on myself right now”), a couple of conceited bridge crewmen (“One time I almost died because I humped a statue”), a giant blob of gelatin (“I gotta say, watching your corpse drift away to this music would be so peaceful”), and an artificial life form who thinks an amputation would make a good practical joke (“The penchant for biological lifeforms to anthropomorphize inanimate objects is irrational”).

And that’s basically the set-up in Seth MacFarlane’s The Orville, a TV series that, as the saying goes, has garnered a cult following, starting first as a network product and then migrating to a subscription video on demand service, with its cult following . . . following. (How many people constitute a cult, anyhow? Never mind.)

If you go to the movies much, you’ve innocently become enmeshed in the latest Hollywood “trend” (more like a nostalgia goldrush) in churning out sequels, prequels, “reimaginings,” and reboots. (Not all remakes, by the way, are a bad thing; John Huston’s excellent 1941 reboot of The Maltese Falcon was the third attempt at filming it, one which succeeded very nicely.)

We view this trend as an admission that they’ve run out of steam and aren’t even trying to be creative, never mind original. Complicating an already bad situation is the unmistakable messianic zeal with which the Tinsel Town elites are willing to cram their brand of political pontificating down unsuspecting audiences’ throats, even if their projects lose them money. (Someone somewhere once observed that in Hollywood influence and ego gratification — embodied in their lay sermons, movies — are the orgasm and money the aphrodisiac, the stimulus by which they achieve satisfaction.) Indeed, until a month ago we had never heard the term “woke” applied to motion picture and television productions, but to a greater or lesser degree just about everything emerging from Tinsel Town seems to have some component of “wokeness” to it.

But we digress. In just about all aspects of art training (and, whatever you may think of them, we can include movie and TV production as art), beginners are encouraged to emulate previous masters in their field, to copy them with an eye to developing their own unique styles later on.

… which brings us back to The Orville. Seth MacFarlane, the executive producer, writer, director, star, and who knows what else on this TV series has taken the normal art training paradigm and junked it. Every single aspect of this show is derived from somewhere else, intentionally so. If you are familiar with S*** T*** (because the latest series producers are a prickly lot, we feel it safer to employ the asterisks), viewing any given episode of The Orville should provoke a feeling of deja vu. Situations, characters, whole plotlines, musical cues, even individual shots are lifted primarily from S*** T***, with S*** W*** and a random collection of components from a bunch of other sci-fi sources, as well.

Everyone has a unique gift; MacFarlane’s gift is in NOT being original (his tiresome cartoon shows demonstrate that) but in being a copycat, the best copycat on the Hollywood scene at the moment. In The Orville, he has done a remarkable thing by blurring the formerly clear-cut distinction between parody and pastiche, the result being a thing unto itself, funny, serious, derivative all at once. For that alone, MacFarlane deserves some sort of Major Award.

Is the series “woke”? Oh yeah. According to what we’ve read, MacFarlane has already received a Major Award, this one from a group of like-minded people who probably wouldn’t object if authorities prosecuted parents as child abusers for providing religious instruction to their children; since very few artists ever alter their deeply felt attitudes (indeed, they constantly draw on them for inspiration), we can expect to see the consequences of that particular frame of mind to continually play out in the series, especially with respect to The Orville‘s continuing “bad guys,” a bone-headed race of aliens whose sole motivation is to murder anyone who doesn’t conform to their religion. (Bone heads. Get it?) Like its S*** T*** predecessors, in this show any person or random cactus that entertains the faintest glimmering of spirituality is automatically a moron in desperate need of rationalist enlightenment. (A case can be made that the science fiction subgenre of literature is the primary conveyance of atheist thought today, but while that might make for a thrilling Ph.D. thesis, we just don’t have the time.)

In spite of what you’ve just read, is it possible to like The Orville? The special effects are excellent; the plots, while totally derivative, mesh nicely with the characters; and the acting is uniformly very good (Scott Grimes’s performance in his story with a simulated woman being Major Award-worthy).

Perhaps the best way for someone who still clings to Middle American values (any of you still left out there?) to fully enjoy The Orville would involve assuming a posture in which index finger and thumb are firmly placed against the proboscis. Everybody else will cheerfully overlook the subtexts and uncritically swallow MacFarlane’s spoonful of sugar. (You remember Mary Poppins, don’t you? “A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down, The medicine go down-wown …”)

Sun 24 Nov 2019

Not to be confused with the much more recent heavy metal rock band from Sweden of the same name, this earlier version who also called themselves The Haunted was a garage band from Montréal, Québec, Canada. The LP below (re-released on CD) played in its entirety, was their only studio album, but there were three compilation albums released later on, in 1983 (2) and 1995.

Sat 23 Nov 2019

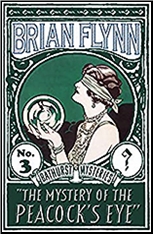

BRIAN FLYNN – The Mystery of the Peacock’s Eye. Anthony Bathurst #3, Hamilton, UK, hardcover, 1928. Macrae-Smith, US, hardcover, 1930. Dean Street Press, trade paperback, October 2019.

He shook his head. Then the Spirit of Audacity and Adventure caught him and held him securely captive. “One day — perhaps, I’ll tell you,†he declared, “till then, you must possess your soul in patience.â€

Let me be clear from the beginning: you won’t have to worry about being caught short by Audacity and Adventure in this book, though if you plan to wade through it possessing your soul in patience is a good idea, indeed it may be your only hope.

The Mystery of the Peacock’s Eye is the third adventure of amateur sleuth Anthony Lotherington Bathurst, whose literary career managed to encompass thirty two volumes of prose, much like that above, between 1927 and 1947 ending in a book Barzun and Taylor called “tripeâ€.

Steve Barge, who writes a fine historical and appreciative introduction to this volume discussing Bathurst seems surprised that Brian Flynn, his creator, was never embraced by the Detection Club or the Crime Writers, but frankly only a paragraph or so in it is pretty clear why. Flynn deserves his own volume of Bill Pronzini’s alternative classics (Gun in Cheek, Son of Gun in Cheek).

That said, his books are fair play mysteries, it’s just there isn’t much at stake in these games. As for Bathurst, having noted that his prospective client writes with a Germanic hand, Bathurst indulges in a very un-Holmesian bit of theorizing: “possibly a German professor who has mislaid his science notebook containing the recipe for diamond-making. That would account for the heavy demands to be made upon my powers of discretion!“. If Holmes indulged in such flights of fancy, Watson spared us them.

Unlucky for us that has nothing to do with the plot at hand.

Bathurst is a bit of a cipher. We are told he is attractive, know his parents are Irish, know he is a fine example of the concept of “Mens Sana†(perfection of mind and body, I take it rejected by Nero Wolfe and Gideon Fell), and pretty much sexless.

Reading about this rather bland superman can make you mourn for the annoyances of Philo Vance or the touchy personality of Roger Sherringham. Flynn talks a better Holmes imitation than he delivers. At least Sapper’s Ronald Standish actually steals some of Holmes brilliant moments of reasoning (along with actual plots).

Aside from such sterling example of prose as that passage above we have Flynn and Bathurst’s seeming inability to use simple words when there is an obscure one to be found in the dictionary. Here is Mr. Bathurst having breakfast in his rooms at the Hotel Florizel (points to anyone who catches the reference to Robert Louis Stevenson’s own sleuth).

I grant I can imagine Peter Wimsey or Albert Campion blathering something to Bunter or Lugg along the lines of, “The matutinal coffee-pot is required this morning …†but for the life of me I can’t imagine Sayers or Allingham using the word as their own without satirical point, and this is only the beginning for our boy Anthony, who shows an equal attraction for his creator’s collections of great quotes, which are dropped like bombshells along the difficult path to a solution.

Despite or because of the nod to Holmes, the book opens well, with a grand ball where the Mr. X from above meets an attractive young lady, Sheila Delaney. A year later Mr. Bathurst at his “matuinal coffee pot†receives a client, none other than the Crown Prince of Clorania (Flynn’s fails pretty utterly at the naming of names business of fictioneering, Clorania is among the worst Ruritanian mythical kingdom names one can imagine, but then Graustark was taken) who is being, like his Bohemian cousin in Conan Doyle, blackmailed over an “affaire†with a young woman who he met at the Hunt Ball at Westhampton a year earlier where Mr. X and Sheila Delaney were so entranced with each other.

But Mr. Bathurst can’t even begin his investigation until Inspector Richard “Dandy Dick†Bannister (one of several Yard men Bathurst collaborates with over the years), one of “the Big Six at the Yardâ€, on holiday in Seabourne is called in about the murder of a young woman by prussic acid in a dentist’s chair, a Miss Daphne Carruthers, and Bathurst receives a desperate cable from his client to come to Seabourne as Miss Daphne Carruthers is the young woman the Prince had his “affaire†with.

Not a headline you see every day.

Further complicating things when Bathurst arrives is the fact Miss Daphne Carruthers is still alive, and the young dead woman unknown.

Not that the average reader needs a lot to make a guess at who the young lady is. “we are in very deep waters, Sir Matthew! ____ _____ has been the victim of one of the most cunning and cold-blooded crimes of the century and it’s going to take me all my time to bring her assassin to justice.â€

Flynn is just off the mark, not quite up to par, neither good enough nor bad enough to really make the effort worthwhile (The “Daily Bugle†continued its bugling.). Flynn falls into the category of British mystery fiction of the Golden Age that was at its very best gold leaf, and at its worst cheap gold paint. In a career that ran to 1947, Flynn never got better, in fact he got worse, because Peacock is probably the best book he wrote.

Granted Flynn has some talent for interesting mystery set ups, just no delivery, though this one does contain a clever bit of misdirection that is without question the reason it is the best regarded of Flynn’s books. He seems to have admired Christie and tried to plot in her class. The ambition is greater than the delivery, though once in a while he is diverting in the right mood.

The detection proceeds divided between Banninster and Bathurst, but the former is no real improvement being almost as long winded as Bathurst as demonstrated by his description of his method.

Huh, seems the proper response to that, though it does have something of a Monty Pythonesque logic to it.

Bathurst himself happily reassures us about the case:

I grant Sherlock Holmes was sometimes hard up for an intelligent conversation with poor old Watson, but he never seems to have talked to himself. I’d also point out nothing really happens rapidly in a Bathurst novel.

In fairness there are some bright moments like this from Sir Matthew Fulgarney.

More of that would have been welcome though they skate perilously close to self parody, and followed by a phrase too far: “He wheezed hilariously.â€

Several of the Bathurst novels are available at reasonable prices in ebook form, and for fans of the genre they are worth to toe dip to see how you feel about them. In the right mood you might find them more fun than I do, certainly if you approach without my past encounters and preconceptions of Flynn and Bathurst..

All said and done, Bathurst out-waits the killer (The golden sunshine of July passed into the mellower maturity of August. August in its turn yielded place to the quieter beauty of September and russet-brown October reigned at due season in the latter’s stead.) who makes the mistake he was predicting and the law pounces, a minor improvement over a books worth of plodding (It did not take an overwhelming supply of intelligence to see that the trouble was coming from the Westhamptonshire neighbourhood), and Bathurst receives the praise for a job well done, which is more than can be said for Flynn.

Approach with caution: Flynn has a typewriter and isn’t afraid to use it as a blunt instument.

Fri 22 Nov 2019

FRANK M. ROBINSON “The Girls from Earth.” Novelette. First published in Galaxy SF, January 1952. Illustrations by Emsh (Ed Emshwiller). Reprinted in The Best Science-Fiction Stories: 1953 edited by Everett F. Bleiler & T. E. Dikty (Frederick Fell, hardcover, 1953); and Stories for Tomorrow: An Anthology of Modern Science Fiction edited by William Sloane (Funk & Wagnalls, hardcover, 1954). Radio: Adapted for X Minus One by George Lefferts: NBC, 16 January 1957. Cast: Mandel Kramer, Bob Hastings, John Gibson, Jim Stevens, Dick Hamilton, Phil Sterling. Announcer: Fred Collins. Director: Daniel Sutter.

This is mostly a story about how mail order brides helped civilize the Old West, only transposed in time and space to mining settlements barely managing to survive on worlds far from Earth. The ratio of men to women in such places is at least 5 to 3. Strangely enough, the ratio of women to men back on Earth also 5 to 3, in reverse.

There is a problem here waiting to be solved, and the solution is easy. Except for one thing. How, and who, is going to implement it? And how will the contingent of men waiting for their new brides accept them, and vice versa? The details you may read for yourself online here, and probably elsewhere as well. (Follow the link.)

At this much later date, while the story can still be enjoyed for its more humorous overtones, any larger appeal may only be of historical interest. In 1952 science fiction was just beginning to move away from scientific puzzles to be solved, if not out and out space opera. In their place were coming stories based on situations and dilemmas as they were expected to rise in the future, but on a more personal level. As is the case here.

In the radio adaptation, streamlined to just over 20 minutes, the implementation of the plan to solve the problem described above is carried out by a couple of con men, hoping to make their fortune by taking off with the money put down of the miners working on Mars before the women from Earth actually arrive. The end result is the same. It’s just gotten to in a slightly different way.