Tue 20 Jul 2021

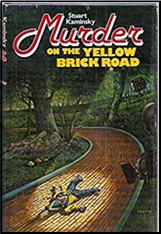

An Archived PI Mystery Review by Jim McCahery: STUART KAMINSKY – Murder on the Yellow Brick Road.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[3] Comments

STUART KAMINSKY – Murder on the Yellow Brick Road. Toby Peters #2. St. Martin’s Press, hardcover, 1977. Penguin, paperback, 1979.

This is the second in Stuart Kaminsky’s historical series starring his 1940s Hollywood private investigator, Toby Peters (a.k.a. Tobias Leo Pevsner), who made his own debut last year in Bullet for a Star. This second entry is by far superior to the first.

Once again, Hollywood stars join the fun in both major and minor roles. In this vehicle Toby ls summoned from the Warner Brothers lot (where he helped Errol Flynn in Bullet) to M.G.M. by an urgent call from Judy Garland, who has just discovered the body of a murdered Munchkin on the still-standing publicity set of Munchkin City from The Wizard of Oz, released more than a year earlier.

Peters is hired by Louis B. Mayer himself to keep the investigation quiet and protect Judy, whose own safety seems at stake. Toby’s interview with the “little” suspect arrested in connection with the murder convinces him of his innocence. Peters, of course, whose wife has already walked out on him and who shares office space with a dentist, is a progeny of the classic Hammett/Chandler tradition. (“My nose is mashed against my dark face from two punches too many. At 44 I’ve a few grey hairs in my short sideburns, and my smile looks like a cynical sneer even when I’m having a good time, but there are a lot around town just as tough and just as cheap. I fit a type, and in my business I was willing to play it up rather than try to cover.”)

And again: “I was doing what private detectives are supposed to do. I was walking the mean streets. I was acting like a damn fool.” Indeed, Raymond Chandler also has a bit part as himself in the novel. He spots Toby while doing research on flophouses and decides to shadow him, but is waylaid for his efforts. Since Toby is the first real detective he has ever met, our investigator lets him tag along on the case so he can drink in some local color and dialogue first hand. A second fatal stabbing, a defenestration, and two attempts on Toby’s life all ensue before the climax, in which even Judy has a hand (or an elbow, to be more exact).

Murder on the Yellow Brick Road is a well-paced and very neat yarn, indeed, even if it doesn’t require a wizard to spot the culprit. The dialogue is crisp and lively, especially between Toby and his antagonistic brother LAPD Lieutenant Philip Pevsner, whose boiling point is nil whenever he runs up against his younger brother.

Add Clark Gable in a minor role as a prospective witness and several other M.G.M. stars in walk-through parts, and it all adds up to quite a pleasant stroll down memory lane as well. Unfortunately, there was a very careless printing job by St. Martin’s Press on the first edition which will hopefully be corrected in subsequent printings, including that scheduled for the Mystery Guild.

Kaminsky’s third work is already in progress and will involve Toby Peters with the Marx Brothers.

Editorial Notes: The title of that next book in the series was You Bet Your Life (1978). There were in all 24 books in the series before it ended.

Jim McCahery was an early member of DAPA-Em whom I met once in a party held at Jeff and Jackie Meyerson’s home. A lot of mystery fans who had met only by zine exchanges met in person for the first time there. I asked Jeff today and he told me that Jim had been a teacher at Xavier High School in Manhattan and had just retired at 60 when he died of a heart attack.

His ambition in retirement was to become a full time writer. Before he passed away, he had written two mysteries:

McCAHERY, JAMES (R.) (1934-1995)

Grave Undertaking (Knightsbridge, 1990, pb) [Lavina London; New York]

What Evil Lurks (Kensington, 1995, hc) [Lavina London; New York City, NY]

Lavina London is described online as a “spry and savvy septuagenarian sleuth … a retired radio actress.” I enjoyed reading both books.