FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

With very little to occupy my time during the pandemic I started to ask myself a less than burning question: What was the worst TV detective series of your childhood? Well, after a few seconds of thought I concluded that there were three that tie for bottom rung of the ladder.

***

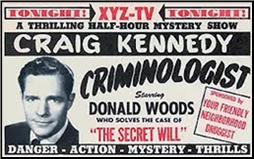

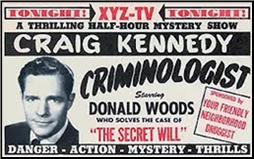

All three date from the same period, the very early 1950s when my parents and millions of other Americans were buying their first sets, so I’ll ignore strict chronology and begin with the one whose roots go back farthest in time. CRAIG KENNEDY, CRIMINOLOGIST was based on the scientific supersleuth character created early in the 20th century by Arthur B. Reeve (1880-1936).

There were several Kennedy movies, the last being a cheapjack 15-chapter cliffhanger serial, THE CLUTCHING HAND (Stage & Screen, 1936), which starred Jack Mulhall and Rex Lease as Kennedy and his newsman sidekick Walter Jameson. Fifteen years after that picture and after Reeve’s death, its producer, Louis Weiss (1890-1963), decided to dip his toes into the waters of TV with an equally cheapjack Kennedy series, starring Donald Woods as the scientific guru and Lewis Wilson, the screen’s first Batman, as Jameson

The first 13 episodes were apparently shot in late 1950 and ‘51, most if not all of them scripted in whole or with a collaborator by B movie veteran Ande Lamb and directed by Harry Fraser (1889-1974), a bottom-of-the-barrel hack if ever there was one. The entire baker’s dozen featured overlapping casts including such long-forgotten thespians as Bob Curtis, Tom Hubbard, William Justine and Stanley Waxman, supplemented by some actors familiar to watchers of Forties B movies and Fifties TV—Ted Adams, Lane Bradford, Stephen Chase, Milburn Morante, Glenn Strange—plus a few who made their mark in TV later, like Phyllis Coates (the small screen’s first Lois Lane) and Jack Kruschen.

Featured in several casts was none other than Jack Mulhall (1887-1979), who had played Kennedy in that 1936 serial but at several years over sixty was obviously too old for the part in the TV series. In what was apparently the pilot episode, “The Golden Dagger†(1950), the star of the next in our triad of terrible series, Ralph Byrd, played a character known as —remember that name, B western fans?—Rocky Lane. Most if not all of the second set of 13 episodes were directed by the producer’s son Adrian Weiss (1918-2001) and also scripted by Ande Lamb.

In England at least nine so-called movies, each consisting of two series episodes, were released theatrically by Anglo-Amalgamated Film Distributors Ltd. “It is to be hoped,†said the British Film Institute’s monthly bulletin, commenting on a member of the ennead, “that even the least discriminating film-goer has the intuition to avoid seeing films as remarkably badly made as this one.†Those masochistic enough to want to sample the series for themselves may check out a few clips and at least one complete episode, “The Case of Fleming Lewis†(1951), on YouTube.

***

DICK TRACY, the second of our terrible trio, also goes back a long way, specifically to the comic-strip cop created in 1931 by Chester Gould. Ralph Byrd (1909-1952) was best known in Hollywood for having portrayed the square-jawed sleuth in four classic Republic serials (1937-41) and two RKO features dating from 1947.

Three years later, when the TV series was launched, he was the obvious choice for the part. The role of his comic-strip sidekick Sam Catchem went to Runyonesque character actor Joe Devlin. Several other characters from the strip—Tess Trueheart, Junior, Diet Smith, B.O. Plenty, Gravel Gertie—appeared off and on in various episodes.

Accurate information about the TV Tracy is hard to come by. A number of websites and even Garyn G. Roberts’ DICK TRACY AND AMERICAN CULTURE: MORALITY AND MYTHOLOGY, TEXT AND CONTEXT (McFarland, 2003) claim that the series consisted of 26 episodes whereas in fact there were 39. The first episodes were broadcast on the ABC network in the fall of 1950 but the series soon switched to a syndicated basis. My best guess is that it began with 26 segments, several of them in two installments, one in four, one in five.

Most of them were scripted by original series producer P.K. Palmer and directed by either of two men, one a nonentity, the other a Hollywood household name. Willard H. Sheldon (1906-1998) was a career assistant director who aside from his TRACY episodes helmed almost nothing else.

His major contribution, if that’s the word, was “Dick Tracy and the Brain,†a 5-part story in which Tracy pursues an underworld genius (Lyle Talbot) whose real name, true to Chester Gould’s nomenclatural principles, is B.R. Ayne. On the other hand, B. Reeves Eason (1886-1956) had directed some of the most spectacular action footage in film history: the chariot race in the silent BEN-HUR (1926), the climactic CHARGE OF THE LIGHT BRIGADE (1936), the Burning of Atlanta sequence in GONE WITH THE WIND (1939). Even with the rock-bottom budgets and laughable working conditions on TRACY, we might have hoped for more from him. Hard cheese.

The four-part “Dick Tracy and the Mole,†pitting Byrd against grizzled old B Western sidekick Raymond Hatton in the part of a master criminal who can’t stand light and roosts underground, is next to unwatchable. The two-parter â€Dick Tracy and Flattop,†in which Byrd’s adversary is a hit man hired to kill him by crime kingpin Namgib (another name in the Chester Gould tradition), is no improvement.

If nothing else, Eason’s TRACY episodes, apparently the only TV work he was ever credited with, confirms the wisdom of Sherlock Holmes’s famous dictum “I can’t make bricks without clay.â€

Later segments including most if not all of the final 13 tended to be complete in 30 minutes. The scripts, written by established pulp crime writers like Robert Leslie Bellem, Dwight Babcock and Todhunter Ballard, included some character names squarely in the Gould tradition, like the murderer Phil Graves in “The Case of the Dangerous Dollars.â€

The directors of these episodes tended to have roots in B Westerns, foremost among them Thomas Carr (1907-1997), who helmed three two-parters and at least five singletons. I got to know Tommy and tape extensively with him when he was in his eighties but I either didn’t know or had forgotten how heavily he’d been involved with TRACY in the dawn years of TV and didn’t ask him to reminisce about the series. (That sound you just heard was a swift kick in the rear, administered to me by me.)

Watching Tommy’s surviving episodes, I sense him struggling to inject a minim of visual quality under impossible circumstances. “Shaky’s Secret Treasure†is unique in that, thanks to the meticulous records kept by actor Dabbs Greer, who played Shaky, we know precisely when Tommy filmed it: on January 22 and 23, 1952, which means it was one of the final 13 segments. Greer’s salary, in case anyone’s interested, was $75 a day.

The series ran regularly on various local stations at least through the mid-Fifties, and a number of episodes—the 4-part “Mole,†the 2-part “B.B. Eyes†and at least four stand-alone segments—can be seen on YouTube. Ralph Byrd didn’t last anywhere near that long. While on vacation soon after TRACY wrapped, he died of a heart attack, on 18 August 1952, at age 43. Like Basil Rathbone with Holmes and Bogart with Sam Spade, he’s remembered long after his death for the character he incarnated.

***

Dating from the same time frame as KENNEDY and TRACY was FRONT PAGE DETECTIVE, a 39-episode series produced by small-screen pioneer Jerry Fairbanks (1904-1995), first broadcast on the short-lived Dumont network in 1951 and rerun times without number on local stations throughout the rest of the Fifties.

Alone among our trio, this one didn’t have a pedigree. The title came from a pulp true-crime magazine but its protagonist, café-society columnist and amateur detective David Chase—described as a sleuth with “an eye for the ladies, a nose for news, and a sixth sense for danger‗was created especially for TV.

“Presenting an unusual story of love and mystery!†the unseen announcer would purr in dulcet tones at the start of each episode. His introduction concluded with: “And now for another thrilling adventure as we accompany David Chase and watch him match wits with those who would take the law into their own hands.â€

Starring as Chase was one-time matinee idol Edmund Lowe (1892-1971), a name familiar to moviegoers for a third of a century before his entry into television. During the 1920s he specialized in suave romantic roles complete with waxed mustache, but the biggest boost in his film career came when director Raoul Walsh cast him opposite Victor McLaglen in WHAT PRICE GLORY? (Fox, 1926), first of the Captain Flagg-Sergeant Quirt military comedies.

His foremost contribution to the detective film came ten years later when he portrayed Philo Vance in THE GARDEN MURDER CASE (MGM, 1936), but he also played a New York plainclothesman of the 1890s opposite Mae West in EVERY DAY’S A HOLIDAY (Paramount, 1938).

By the early 1950s Lowe had begun to show his age, and in FRONT PAGE DETECTIVE he looked all too convincingly like a man of almost sixty who’s determined to pass himself off as 25 years younger. In many an episode he’d romance the woman in the case, rattle off a few deductions—once he reasoned that a letter supposedly from an Englishwoman was a forgery because the writer used the U.S. spelling “check†rather than the British “cheque‗and then collar the villain personally after a pistol battle or fistfight underscored by Lee Zahler’s background music for Mascot and early Republic serials.

Supporting Lowe were Paula Drew as Chase’s fashion-designer girlfriend and crusty George Pembroke as the inevitable stupid cop. Appearing in individual episodes were such stalwarts of TV’s pioneer days as Joe Besser, Rand Brooks, Maurice Cass, Jorja Curtright, Jonathan Hale, Frank Jenks and Lyle Talbot.

As with KENNEDY and TRACY, filming was 99% indoors, on some of the cheapest sets ever seen by the televiewer’s eye except perhaps for those used by the other members of our trio.

The director of every episode I’ve seen recently was Fairbanks’ production supervisor Arnold Wester (1907-1976), who is not known to have directed anything else afterward. And just as well: apparently his idea of directing was to make sure the camera was pointed at the actors and leave the set.

Many scripts were by veterans of pulp detective magazines and radio like Robert Leslie Bellem (also, as we’ve seen, a TRACY veteran) and Irvin Ashkenazy, with an occasional contribution by Curt Siodmak, author of the classic horror novel DONOVAN’S BRAIN.

At least nine episodes of the series are accessible on YouTube. The rest seem to have vanished but their gimmicks can often be deduced from the brief descriptions in crumbling issues of TV Guide.

In “The Case of the Perfect Secretary†Chase tries to find out why Dr. Owens, the inventor of a synthetic cortisone, didn’t show up for a scheduled lecture. He finds Owens’ laboratory deserted and later discovers that the doctor has been murdered, the letter M imprinted on his forehead. It takes no Charlie Chan to figure out that the M is most likely a W.

“Honey for Your Tea†finds Chase looking into the claim of a young actress that her fiancé was brutally murdered by her dramatic coach (Maurice Cass), a gnarled and crippled old man whose hobby is beekeeping. Anyone want to bet that this isn’t the old bee-venom poisoning shtick?

In “The Other Face†Chase investigates the death of a handsome actor who “accidentally†fell from his penthouse terrace shortly after telling his psychiatrist of his desire to fall through space. If the murder victim didn’t turn out to be not the actor but his look-alike understudy, toads fly.

Other episodes seem to have more intriguing storylines. In “Napoleon’s Obituary†a man named for Bonaparte dies the day after asking Chase to write his death notice, and the trail leads our sleuth to a house whose inhabitants are all named after historic figures.

In “Ringside Seat for Murder†Chase witnesses a bizarre murder during a wrestling match where one of the athletes (using the term loosely) is stabbed in the back with a poisoned dart while pinned to the mat by his opponent.

FRONT PAGE DETECTIVE never pretended to be a classic, but for all its clichés and Grade ZZZ production values it was, like KENNEDY and TRACY, a pioneering effort in tele-detection that deserves perhaps a wee bit more than to be totally forgotten.