Tue 11 Aug 2020

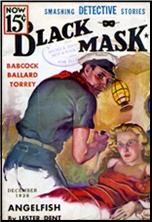

Archived Pulp Fiction Review: HERBERT RUHM, Editor – The Hard-Boiled Detective: Stories from Black Mask Magazine.

Posted by Steve under Pulp Fiction , Reviews[21] Comments

HERBERT RUHM, Editor – The Hard-Boiled Detective: Stories from Black Mask Magazine, 1920-1951. Vintage, paperback original, 1977.

I don’t think that anyone would argue the fact that Black Mask was the best detective pulp magazine around. It died a lingering death after World War II with all the other pulp magazines, but in its pages during the 1920s and early 1930s were some of the toughest detectives in the business — and the freshest writing on the American scene.

The private detective as a two-fisted gallant knight , loyal to his clients and deadly to the undesirable, criminal element of society was a far cry from the sedate British counterpart, and as invented by Carroll John Daly, Dashiell Hammett, Erle Stanley Gardner, and a somewhat later Raymond Chandler, became a much imitated feature of American culture, with copies and variations still alive today.

We’re told that Carroll John Daly’s “The False Burton Combs” (December 1922) marks the first usage of American colloquial speech in Black Mask, the slangy tough vernacular that was to become its trademark. For a time Daly was Black Mask‘s most popular author, though today he’s perhaps remembered only by collectors. The story, about the impersonation of a rich boy in gangster trouble, is a good one. It’s told by the soldier of fortune hired for the job; he’s neither crook nor policeman., but he’s willing to make a quick buck, and equally willing to take his knocks when it comes time.

The tough guy narration goes down smooth and natural, but the narrator is still an innocent rube behind his image of worldly sophistication. I suspect Daly later was undone trying to out-tough himself with every story he wrote later on, and forgot the schmaltz that helps pull this one off.

From the very same issue comes “The Road Home” by Dashiell Hammett, under his Peter Collinson pseudonym. It begins as a Stanley-meet-Livingston adventure that in only four pages says more about the inner compulsion of men who spend their lives hunting down criminals than in some novels. Understated and maybe the best story in the book, it’s hard to believe that this is the first time it’s been reprinted.

“The Gutting of Couffignal” (December 1925) has been around many times, and in fact I think it’s the first story by Hammett I ever read. It gets better every time. After the wealthy island of Couffignal is systematically looted by machine-gunning terrorists, the Continental Op, gets to demonstrate both his detective ability and his unswerving loyalty to that choice of career. I was unhappy that in the book’s introduction, Ruhm chose to quote from the final few lines to illustrate the point. You really deserve to get the full impact in context.

I have a weakness for Hollywood detectives, and “Kansas City Flash” (March 1933) by Norbert Davis takes full advantage of that weakness. When Mike Hull investigates the kidnapping of Doro Faliv, Hollywood’s latest rage in leading ladies, success only reveals yet another sad story midst the twistedly tangled plot. Intended or not, in many ways Doro Faliv is symbolic of the famous 1930s glamor capital of the world. Hiding behind its glittering facade is a brittle sadness and emptiness that all the many love affairs and busy publicity agents were never able to cover up.

Frederick Nebel’s “Take It and Like It” (June 1934) is meant mostly for fun, but in doing so Kennedy and MacBride form the prototype for many 1ater wisecracking detective teams. Kennedy’s a screwy newspaper reporter not averse to a drink or two, while MacBride is his long suffering police captain friend. This time around, however, MacBride has orders to pick Kennedy up for murder, to the glee of the reporter’s enemies on the D.A.’s staff. Nevertheless Nebel has everything under control, and he easily keeps it way this side of flat-out comedy.

It may be heresy to say so in print, but I’ve never really been a diehard Raymond Chandler enthusiast. “Goldfish” (June 1936) would seem to do well as illustration. The story itself is about a pair of missing pearls, stolen nineteen years before and never recovered by the insurance company. Carmady’s late start on the case doesn’t mean that the fireworks are over – in fact, the treachery and bloodshed have just begun. Chandler’s verbal imagery dazzles, I admit, but more often than not, it’s merely for show and also quite useless to the plot, which has all the connectivity of a plate of hash-browns.

Possibly I’m missing something, as I keep getting the feeling that some key element is hanging just out of my grasp. Chandler and I are fractionally out of sync.

Lester Dent was not really a Black Mask writer, as he wrote only a couple of stories that appeared in the magazine. He spent most of his writing career doing a couple hundred Doc Savage novels. “Angelfish” (December 1936), the story included here, is plagued by Dent’s characteristic semi-literate understatement, but it’s for sure a tough story, told with hurricane ferocity. His hero is a tall, lanky detective named Sail, who dresses all in black. The chase is after some aerial photos of a promising oil field. Uncomplicated, in a breathless way.

At another extreme is Erle Stanley Gardner, who was so prolific in short pulp work that his bibliography fills a short book in itself, “Leg Man” (February 1938) was a late-appearing pulp story, and it exhibits both Gardner’s unmistakable ponderous dialogue and the elaborate plot machinery that may creak here and there but yet meshes with intricate mastery. Pete Wennick is the leg-man, doing a high-priced law firm’s dirtier investigative work, which may include actively defusing a blackmail scheme. Even though less complicated than usual for Gardner, it still fooled me.

Any anthology taken from the pages of Black Mask needs a Flashgun Casey story by George Harmon Coxe. In “Once Around the Clock” (May 1941) the famed photographer for, the Express requires only a quick twenty-four hours to help an ex-piano player out on parole escape a murder rap. I wouldn’t say Coxe is a bad writer, but the best I could say is that he’s indifferently average.

How then has he lasted so long? Take Casey. He’s a down-to-earth guy, with cares and problems of his own, as well as concerns for others. If this makes him a sentimental slob instead of just another hard-boiled character, I’d say that’s why Coxe can keep finding something that readers can keep on enjoying.

Luther McGavock is the only detective I know of who works out of Memphis, Tennessee, and his cases always seem to take him deep into the hill country of the South. In “The Turkey Buzzard Blues” (July 1943), Merle Constiner gives us a deceased aristocratic gentleman of another age, a frowsy political hack, moonshiners, a tired sheriff suffering from the miseries, and a pet buzzard. There’s more than a tinge of comic mayhem throughout, but it’s all too durn much for me, and at 71 pages, far too long.

I’d call William Brandon’s “It’s So Quiet in the Country” (November 1943) Runyonesque if I’d ever read enough Damon Runyon to be sure. A city type mixes it up in rural Vermont with a couple of Poe scholars who find they are in need of his burglarizing services. Kind of funny, but no more.

We’re now in the era when straight crime stories were predominant. After a couple of decades perhaps readers and authors both were tiring of the hard-boiled detective. “Killer Come Home” (March 1948), by Curt Hamlin, combines anger with domestic tribulations. Paul W. Fairman tells about a young kid learning about the big time in “Big Time Operator” (July 1948). In “Five O’Clock Menace” (May 1949) Bruno Fischer deals with undercurrents of human nature in a small-town barbershop. All short and all inferior to the crime shocker tales that Manhunt later brought to perfection and rode to success on.

But what results is a true cross-section of Black Mask magazine for the length of its existence. If the quality of the stories begins to slide downward from the beginning of the book to the end, so did the magazine as a whole. I do wonder why something by John D. MacDonald wasn’t used to close the book, as JDM in particular was a strong part of the upturn in quality in the crime story in the 1950s, as the pulps died, and writers turned to paperback novels, and the previously mentioned Manhunt.

One might wish for all the stories from the 1920s, but all but a few that were used have been reprinted for the first time, and the truth is that there’s plenty of stories left for more pulp detective anthologies as good as this one. The best stories, all worthy of “A” ratings, plus or minus, are the pair of Hammett’s, and the ones by Daly, Davis and Dent.

Overall Rating: B plus.