Fri 8 Aug 2008

Review: GEORGE HARMON COXE – Fashioned for Murder.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Covers , ReviewsNo Comments

GEORGE HARMON COXE – Fashioned for Murder.

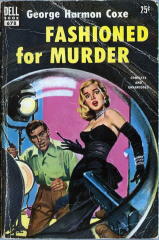

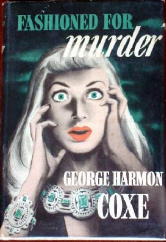

Dell 678; paperback reprint; no date stated, but probably 1953. Hardcover edition: Alfred A. Knopf, 1947.

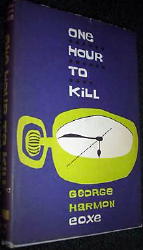

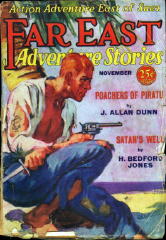

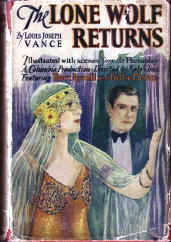

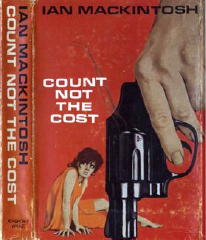

Take a look at the cover of the paperback edition and compare with the one on the hardcover. Both are appropriate for their respective venues — sales mostly to libraries for the hardcover, where the artwork on dust jacket was all but incidental, versus sales on newsstands and drugstore spinner racks. The one on the paperback is nothing but eye-catching, and it does its job well. Besides telling you something about the story itself, wouldn’t it make you a whole lot more in the mood to fork over the 25 cents to took back then to take it home?

And in the credit-where-credit-is-due department, the Dell cover was painted by Fred Scotwood, a new name to me, but done in very much a 1950s style, and it’s a pretty good example of GGA (Good Girl Art) as well. (According to Google, Scotwood appears to have done at least two other covers for Dell in the same time period, but so far, that’s all that I’ve found out about him.)

As for the book itself, assuming that you’ve not tired of this mini-symposium on the author that’s developed this week, it’s one of Coxe’s non-series books, and without attempting to soften my comments any, it’s not one of his better ones, series or not.

It starts out as a yawner, and in subsequent events it never manages to work its way up any higher than that. Even the hero’s name, Jerry Nason, a young fashion photographer based in Boston, bothered me. It reminded me too much of that book in which Atlas Poireau, Trajan Beare, Spike Bludgeon, Mallory King, Sir John Nappleby, Jerry Pason, Lord Simon Quinsey, Miss Fan Sliver, and Broderick Tournier all combine efforts to solve a murder together. (You do know the one I mean?)

That’s a minor quibble. Forget I brought it up. Fashioned for Murder begins with Pason taking a series of photos of a model wearing some costume jewelry she happened to bring with her. The two of them hit it off, but a date they’d scheduled for later failed to come off. Pason decided to write it off as just one of those things until they meet again at another shoot.

The jewels, it seems, have caught someone’s eyes, Linda Courtney has become very popular, and she needs to tell Jerry about it. Not only that, when she does, Jerry becomes a target, too. The two of them are held up in his studio, and the fake jewels are stolen. (This is were the front cover comes in.)

Now you know as well as I do that the jewels are not phony, but it seems to take way too long for Linda and Jerry to catch on, even though he follows her back to Manhattan where she lives to check into some of the other strange things that had happened to her.

When one of the participants in the aforementioned activities comes to Linda’s apartment only to collapse dead on the carpet, Jerry commits an amateur detective’s most common mistake — he becomes an amateur detective. He decides to investigate the dead man’s flat himself and holds back evidence from the police, for reasons that almost sound good, but in reality are as substantial as the dental floss the rest of the story is stitched together from.

I even figured out who did it, which I have to confess does not happen all that often, so when it does happen, it is not my desire to pat myself on the back about it. As I said earlier, this is not one of Coxe’s better stories, but at least Linda and Jerry wind up in each other’s arms at the end.