Fri 11 Jul 2008

Archived Review: MANNING LEE STOKES – The Dying Room.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Characters , Crime Fiction IV , Reviews[21] Comments

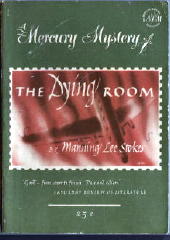

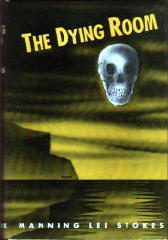

MANNING LEE STOKES – The Dying Room. Mercury Mystery #124; digest-sized paperback; no date stated. Hardcover edition: Phoenix Press, 1947.

This is strange — really strange, as a matter of fact. There are six copies of this book available for sale on ABE as I type this, and five of them are the paperback version. Guess which one’s the least expensive? The hardcover edition from Phoenix. Even without a dust jacket on the hardcover, explain that if you can.

Manning Lee Stokes was born in 1911 and died in 1976, and at best, he had what you might call a mixed writing career. The Dying Room was one of his earliest books — his first four were published by Phoenix, beginning in 1945, and in chronological order, this one’s the third. From Phoenix he went to paperback originals (Graphic Books) and then wrote several others for another designed-for-libraries hardcover publisher, Arcadia House. One book was published Dell in 1958, but from 1960 on, he wrote nothing that appeared under his own name.

He wrote some of the early Nick Carter spy thrillers from Award in the 1960s, for example, a few of the John Eagle “Expeditor” men’s adventure novels from Pyramid in the 1970s as by Paul Edwards, and as Ken Stanton, all eleven of the “Aquanauts” books (with leading character Tiger Shark) that came out from Macfadden and Manor, also in the 1970s. (I have all the Expeditor books, I believe, but I have no explanation as to why I have NONE of the Aquanauts books.)

Stokes also wrote some of the sex-oriented SF-Fantasy “Blade” novels from Pinnacle, or so I’m told, but there’s certainly no reason to go into that, or at least not here. One other series character whom he created and who is worth mentioning is Christopher Fenn, who solved a couple of the cases from Arcadia House in the late 1950s, including The Case of the Presidents’ Heads, shown smoewhere below and to the left. Fenn was a private eye or criminologist of perhaps no great renown, but he is listed on Kevin Burton Smith’s PI website, so he has not been totally forgotten.

But there is private eye that Kevin does not know about — a rare event — a gent called Barnabas Jones who appeared in both The Wolf Howls “Murder” (Phoenix Press, 1945) and Green for a Grave (Phoenix Press, 1946). And something that Al Hubin does not know about (yet) is that Barnabas Jones also shows up for a short appearance in The Dying Room. Even though Jones is not the leading character and his part is small, his role is a relatively important one, substantially more than a walk-on or cameo, and I’ll get there very shortly.

Before I do, however, let me say this up front. The Dying Room is a much better book — and detective novel — than I expected it to be. Phoenix Press is not noted for its gems and works of art in the world of crime and mystery fiction, but you could do much worse than finding a copy of The Dying Room to read somewhere and somehow, hopefully not paying too much for it, no more than ten to fifteen dollars or so, and maybe less if you’re lucky. (My copy cost me five dollars if you were to split the money up as part of a group lot, and when I found it among the others, my first reaction was that I paid too much.)

Telling the tale is Tom Fain, an ex-soldier with a splinter of a German shell embedded in his brain. About to be moved into the “dying room” at the Fort Tyner station hospital after his latest unsuccessful surgery, Fain decides to make a break for it. And with the help of a sympathetic nurse’s aide named Helen, escape he does.

On his way to see his ailing stepmother, the only mother he has ever known, he stops to visit with an old friend — the aforementioned Barnabas Jones, who offers him a job, but with other things on his mind at the time, Fain turns him down. (Mr. Jones makes another appearance and more importantly, in his professional capacity, later on.) Failing to reach his stepmother before she died, and avoiding a pickup by a pair of MP’s on his trail, Fain heads back to New York (and Helen) on an airplane — which is where the story begins, or at least the mystery part.

Fain sits next to a good-looking girl — no, change that, make it a beautiful girl — with whom he strikes up a lively conversation. Things are going well, but there’s nothing like a small disaster to get a story really going. Both Fain and the girl survive the crash. He’s more or less OK, but she is not. Her memory is gone, and a new one — one of her former life — has replaced it. Unfortunately there is a two-year gap in what she remembers. She doesn’t remember Fain, but being convinced that he helped save her life, she invites him to her new (old?) home to recover.

There was a question mark there, as you will have noticed. Is the girl the missing heir to a considerable fortune? Or is she a fraud? Fifty million dollars is at stake. (I did say considerable.) Several persons try to hire him — it turns out that he, before the war, was a private eye himself. And as it turns out, and not too surprisingly, someone is playing a dangerous (and deadly) game, and Fain, as he quickly discovers, was never given the rules under which it’s being played.

But as a detective, Fain gives his clients their money’s worth, and in similar fashion does Stokes the author. A six-point summary on page 98 is as precise and to the point as any I’ve read in a work of detective fiction in quite a while. No power point presentation could have produced anything better.

The ending gets a little too melodramatic, perhaps — well, no perhaps about it — and the prologue most certainly could have been ditched, which very nearly goes without saying, as most prologues could be (should be) ditched, but (and this is a big but) this book is as entertaining as anything I’ve watched on television this week.

That someone never recognized that this book would make for an awfully good movie is something to be regretted. Filmed in black-and-white, with some professionally done noir-ish touches, perhaps, maybe even a great one.

[UPDATE] 07-11-08. Looks like I never told Kevin about Barnabas Jones, but I will today. (One of course wonders immediately if the gent is related to the later Barnaby Jones of TV fame. Probably not. There are a lot of Joneses in this country.)

Barnabas Jones’s brief appearance in The Dying Room is now included in Part 5 of the online Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, along with a complete listing for each of the PI series he did, both early in his career.