Wed 17 Apr 2013

A Review by Dan Stumpf: THE BIG BOODLE (Book and Film).

Posted by Steve under Action Adventure movies , Reviews1 Comment

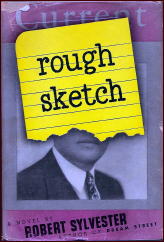

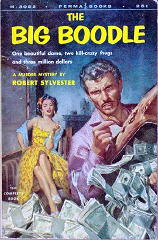

Dated but fun is Robert Sylvester’s The Big Boodle (Random House, 1954; Permabook M-3022, 1955) set in pre-Castro Cuba and dealing with PI Ned Sherwood’s efforts to disentangle himself from an elaborate counterfeit scheme involving Mexican film stars, Cuban hit-men, ex-revolutionaries and corrupt officials.

There’s a lot of foreshadowing in the early pages — so much that I nearly gave up on this after Sherwood said for the umpteenth time that he’s too smart to get mixed up in etc.etc — and I saw the plot resolution come marching down Main Street from a long ways away, but Sylvester creates some interesting characters, handles them effectively, and throws in enough action (also very well-handled) to make a worthwhile read. His hero also has a cute habit of comparing himself to Philip Marlowe, Nero Wolfe and other fictional PIs, sometimes very cleverly.

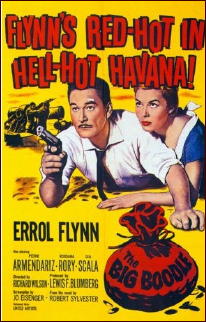

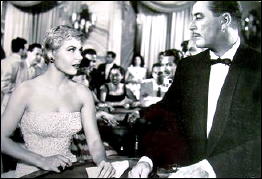

This was, incidentally, turned into one of those lackluster films of Errol Flynn’s later years (UA, 1957) of which I am so morbidly fond. It offers some fine Cuban locations (Unlike We Were Strangers, reviewed here, Flynn appears to be actually filming in them.) and Pedro Armendarez appears once again as a cop, but aside from this it bears little relation to Sylvester’s work.

Directed by Richard Wilson and written by Jo (House of the 7 Hawks) Eisinger, it changes Ned Sherwood into a world-weary croupier, handed a stack of counterfeit money by a mysterious femme you-guessed-it and subsequently beaten, shot at, picked up by the police and generally chased around Havana until they run out of picturesque locations, whereupon, having lumbered up to a respectable running time, things wrap up without too much fanfare.

Critics at the time remarked that by now Flynn was good at looking world-weary, but he seems more movie-weary than anything, visibly sucking in his gut and trying to focus his bleary eyes as he reads lines to the other actors mired in front of him. And aside from the location shooting, little care seems to have been taken with The Big Boodle; in one fight scene, Flynn’s part is taken by a stunt double who looks so little like him that I actually re-wound to see if I’d missed a part where someone else comes into the room.

This is must-see for fans of the late actor, but anyone else would be well-advised (as Flynn himself should have been) to steer clear of it.