Wed 3 Jan 2024

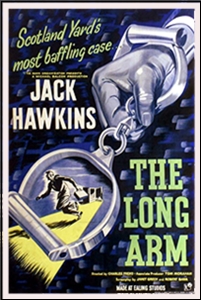

A Movie Review by David Friend: THE THIRD KEY (1956).

Posted by Steve under Crime Films , Reviews1 Comment

THE THIRD KEY. J. Arthur Rank / Ealing Studios, UK, 1956. Original title: The Long Arm. J ack Hawkins, John Stratton, Dorothy Alison, Michael Brooke, Sam Kydd, Glyn Houston. Director: Charles Frend.

A business in Westminster is burgled, and when the police arrive they are greeted by a nightwatchman. The safe has been opened with a key and its contents stolen. The following day, however, it emerges that the nightwatchman was actually the thief in disguise, and the real nightwatchman is in hospital with a burst appendix. Superintendent Tom Halliday (Jack Hawkins) and his new Detective Sergeant Ward (John Stratton) begin their hunt for the fraud.

With the help of his boss and friend Chief Superintendent Jim Malcolm (Geoffrey Keen), Halliday discovers that there have been more than a dozen safe-breaking jobs all across Britain, with each involving the same make of safe.

With no suspects at the manufacturer, the case seems to have reached a dead end, until the thief strikes again and an innocent bystander is killed with the getaway car. The vehicle is later found in a scrapyard, inside of which lies a newspaper that leads Halliday and Ward all the way to Snowdonia, North Wales, and a Mr Gilson, a deceased former employee of the safe manufacturer.

The pair discover that there are twenty-eight identical safes in London. The most lucrative haul will come from one that is located at the Royal Festival Hall, where a trap is duly set for the thief…

This mid-fifties police procedural plays like an ever so slightly grittier episode of Dixon of Dock Green, with always-reliable Jack Hawkins, famous at the time for playing resolute men of sturdy, sensible authority, as the investigating officer. An almost documentary style keeps this part of the realist school of detective drama, with only occasional moments of gentle humour, mostly between Halliday and his new sidekick, who, in a running gag that’s more of a leisurely stroll, is forever interested in getting off work to see his girlfriend.

The cast is made up of dependable stalwarts of the era, with the likes of Geoffrey Keen (so often excellent in these sort of roles, who sometimes got the chance himself of playing the main detective in lower-budgeted B-films), Sydney Tafler (a big favourite of mine, here playing a character named ‘Creasey’, presumably because of big-name crime writer of the time John Creasey), and Ralph Truman.

Ian Bannen also appears as the victim of the hit and run, to whom Halliday somewhat insensitively questions while on his death bed, and would go on to play the lead role in the amiable Scottish farce Waking Ned over forty years later.

A bunch of other actors with walk-on roles, such as Stafford Johns, would go on to appear as police officers again in the rather more grim Z Cars and Softly, Softly, a dramatic direction which would lead to The Sweeney and everything else that makes The Third Key now seem antiquated and, despite its efforts at realism, a little unsophisticated.

That’s probably ungenerous, as middle-class police investigating mostly non-violent crimes is no less realistic than cockney, blue-collar police chasing rapists, but it nonetheless feels more genteel when you have Hawkins’ wife fussing about him being late for tea.

She is, by the way, one of only three women to be given any meaningful role, out of five who appear in the whole film, while most of the cast are middle-class, middle-aged men, with the only ones left over being a street-seller hawking his wares, and Nicholas Parsons as a beat constable.

In fact, thanks to a scene in which Halliday’s son has a birthday party, and another in which a young urchin played by Frazer Hines (of ‘60s Doctor Who and evergreen rural soap Emmerdale) offers a significant lead, there are several more prepubescent boys in the film than women.

Much of which you have to accept with a picture of this vintage, not least as these glimpses into a bygone era are often so interesting, with the location work in particular standing out. The narrative itself may seem a little ho-hum, with the only action being an exciting finale in which Hawkins grips recklessly to the bonnet of an escaping car (the idea of handcuffing the villain not having occurred to the experienced detective).

The film isn’t long, and more focused and markedly less grim than its spiritual successor Gideon’s Day a couple of years later, in which Hawkins plays another Scotland Yard man struggling to juggle serious police work with his home life and family. The main difference there is that he has a teenage daughter instead of a young son, and his wife is rather less worried about him.

Rating: ***