Thu 21 Aug 2014

A Movie Review by Jonathan Lewis: JOHNNY APOLLO (1940).

Posted by Steve under Crime Films , Reviews[3] Comments

JOHNNY APOLLO. 20th Century Fox, 1940. Tyrone Power, Dorothy Lamour, Edward Arnold, Lloyd Nolan, Charley Grapewin, Lionel Atwill, Marc Lawrence. Director: Henry Hathaway.

Johnny Apollo is an crime film that benefits greatly from an exceptional cast, good pacing, and notable proto-noir characteristics. Directed by Henry Hathaway, the film stars a dynamic Tyrone Power as Bob Cain, a somewhat idealist college student who, in order to help get his embezzler father (Edward Arnold) out of state prison, transforms himself into a lightweight gangster named Johnny Apollo. Of no real help to him is his father’s unpalatable lawyer, portrayed by Lionel Atwill.

The story follows Cain (Power) as he teams up with a crooked and drunken attorney, Emmett Brennan (Charley Grapewin), and a gangster named Mickey Dwyer (Lloyd Nolan), to earn money so he can get his father out of prison. Joining them on their not particularly wild ride through crime is Dwyer’s girl, Lucky (Dorothy Lamour), who begins to loathe Dwyer. She also develops romantic feelings for Johnny Apollo/Bob Cain.

Things get dicey when Brennan decides to double cross Dwyer. This leads us to an ice pick scene wherein Dwyer kills Brennan, a scene that begins with a staff member in a Turkish/Russian bath utilizing an ice pick. You just know what’s coming next! And if that’s not enough, the staff member leaves his workstation with the pick stuck there alone in the pile of ice. The camera captures it perfectly. Soon enough, Dwyer picks up the ice pick and enters the steam room. You don’t see him kill Brennan, but the callous nature of the crime is implied.

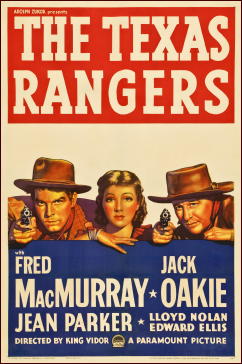

Dwyer (Nolan) is a brute and a sadist, but he’s also capable of charm and genuine affection. In some ways, he is a more urbane, but crueler, version of Bogart’s character in The Petrified Forest. Bob Cain/Johnny Apollo is clearly the film’s protagonist, but Dwyer is just a bit more interesting of a character. Much as in The Texas Rangers, which I recently reviewed here, Nolan is very good in portraying a villain.

About those noir characteristics I mentioned earlier. Shadow and lighting are often utilized to convey meaning. When we first see Nolan’s character, he’s standing in a courtroom waiting to be sentenced. His face is haggard and dark, signifying his violent side. Later on, upon being freed from jail and now back in his familiar surroundings with Lucky by his side, his face appears significantly lighter in tone.

Power’s character’s psychological descent is also conveyed through changes in lighting. When we first see him, he’s college student Bob Cain, not Johnny Apollo. He has a soft face and is resplendent in the sunshine, palling around with his college classmates and posing for a photograph shirtless. After transforming himself into Johnny Apollo, however, he soon gets a black eye in an altercation with one of Dwyer’s former associates.

Worse still is Johnny Apollo’s appearance upon visiting his father in prison for the first time. We see his darkened face, almost angular like Dwyer’s through bars, foreshadowing what fate awaits him in the near future. In one of the film’s next-to-final, albeit very brief, scenes, set in a darkened prison cell, we see Johnny Apollo without a trace of that soft light in which we first saw cheerful Bob Cain.

The film’s biggest flaw is in its slightly clumsy method of introducing its characters. The first two people we see in the movie are Bob “Pop†Cain (Arnold) and his lawyer (Atwill). For the next half hour or so, Atwill seems as though he’s going to be a significant figure in the film, but he soon disappears completely.

The scene in which Dwyer (Nolan) is first introduced, however, is very brief and is immediately followed by a couple of quick scenes in which random, unimportant characters, such Pop Cain’s cellmate are introduced, never really to be seen or heard much from again.

When we first see Brennan, he’s merely standing by Dwyer’s side at the latter’s sentencing. Although he makes a few facial expressions, he doesn’t have a speaking part in the film until later on. I found this an odd way to introduce a character that the plot will ultimately turn upon. That said, the film’s strengths greatly outweigh its weaknesses.

In conclusion, Johnny Apollo is an eminently watchable and significantly above average crime film. Although the film does have some proto-noir characteristics and a seemingly doomed protagonist, it ends up having a light, happy, and somewhat pat ending.

But the film does show the dark side of human nature. It also touches upon the question of fate and destiny. Look, in particular, for the black (or dark colored) cat crossing Bob Cain’s path right before he ascends the staircase to Brennan’s office for the very the first time. That tells you something.