Thu 20 Aug 2009

Addenda to CRIME FICTION IV – Harold Child to Robert Christie.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Crime Fiction IV[5] Comments

Prompted by the recent addition to the online Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, I’ve decided to begin annotating the entries again. I’ve been remiss in doing so since last December, in spite of strong admonitions to myself, and I’ve fallen way behind.

All of the entries below are now online in Part 34. Posting the entries here on the blog means all the more visibility for them, however, and from past experience, the extra exposure never hurts. Comments, additions and/or corrections are not only welcome but strongly encouraged.

CHILD, HAROLD (HANNYNGTON). 1869-1945. Add: biographical information. Born in Gloucester, England; actor; literary and drama contributor to London Times from 1902; drama critic for Observer 1912-1920, with a number of writings on the history of drama. Also a novelist with many stories and articles contributed to newspapers and magazines of the day. Author of one book included marginally in the Revised Crime Fiction IV:

-Phil of the Heath. Pearson, UK, hc, 1899. Setting: Bristol (UK), 1831. [A romantic tale of the Reform Bill period.]

CHILD, NELLISE. Add: Pseudonym of Lillian Lieberman Gerard Rosenfeld, 1901-1981, q.v. Born Lillian Lieberman, the author’s first husband was Frank Gerard, an automobile saleman; she later married Abner G. Rosenfeld, a Chicago real estate developer. A journalist and playwright, her work includes the Broadway play Weep for the Virgins. Under this pen name, the author of two detective novels included in the Revised Crime Fiction IV. SC: Detective Lt. Jeremiah Irish, in each:

The Diamond Ransom Murders. Knopf, hc, 1935; Collins, UK, hc, 1934.

Murder Comes Home. Knopf, hc, 1933; Collins, UK, hc, 1933. [After writing a note to the L. A. police department, a collector of Spanish art is found dead in his library.]

CHILD, RICHARD WASHBURN. 1881-1935. Add: biographical information. Born in Worcester, Massachusetts; educated at Harvard Law School. Ambassador to Italy, 1920-1924; contributor of articles on political and social themes to magazines. The author of two novels (one marginally) and two story collections included in the Revised Crime Fiction IV. Of the two collections, the one cited below includes a story which has been the basis for several film adaptations:

The Velvet Black. Dutton, hc, 1921; Hodder, UK, 1921. Story collection. Silent film, from ss “A Whiff of Heliotrope”: Cosmopolitan, 1920, as Heliotrope. Also: Paramount, 1928, as Forgotten Faces. Also (sound film): Paramount, 1936, as Forgotten Faces. Also: United Artists, 1942, as A Gentleman After Dark. [Synopsis of the 1920 silent film: A prison inmate obtains his release in order to rescue his daughter from the clutches of a blackmailer.]

CHILDERS, JAMES SAXON. 1899-1965. Born in Birmingham, Alabama. Professor of literature, newspaper editor, and publishing executive. Add: Educated at Oberlin College and Oxford University, where he was a Rhodes Scholar. Author of two espionage novels included in the Revised Crime Fiction IV. See below:

The Bookshop Mystery. Appleton, US, hc, 1930. Setting: England. “A double appeal will lure the reader of this mystery story on: in the mellow atmosphere of rare books and famous bookshops is played out a tense intrigue between the secret agents of great nations.”

Enemy Outpost. Appleton, US, hc, 1942. Setting: Canada. “An action-packed story of adventure, intrigue, and romance which is guaranteed to keep you on the edge of your chair. A story of a desperate attempt by Nazi saboteurs to dynamite American industry.”

CHRISTIE, ROBERT (CLELAND HAMILTON). 1913-1975. Add as a new author. Lived in Montreal and Ottawa, Canada.

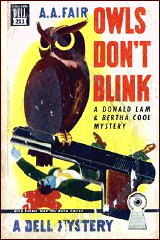

Inherit the Night. Farrar, hardcover, 1949; Hale, UK, hc, 1951. Setting: South America. “An evil stranger destroys the serenity of an Andean village and eventually himself.” [The cover shown is that of the reprint Pyramid paperback, R279.]

![ANONYMOUS [WYLIE] The Smiling Corpse](https://mysteryfile.com/blogImg809/Anon-Corpse.jpg)