Mon 27 Jul 2009

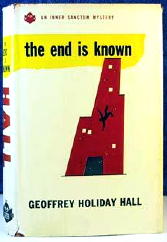

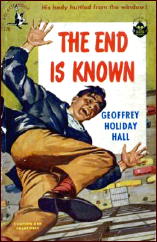

GEOFFREY HOLIDAY HALL – The End Is Known. Simon & Schuster/Inner Sanctum Mystery, hardcover; 1st printing, February 1949. Condensed version appeared in Cosmopolitan magazine, December 1950, as “Who Saw the Man Die.” Pocket #776, paperback; 1st printing, February 1951.

Not a book nor an author I was familiar with when I was recently attracted to it by its cover, and for good reason, I think you might say. Geoffrey Hall wrote only one other mystery, that being The Watcher at the Door (Simon & Schuster, 1954), a spy thriller set in Vienna which got a short notice in Catalogue of Crime by Barzun and Taylor.

In my opinion, though, I think The End Is Known should be far better known than it is. Far from being a spy novel, it’s a mystery that’s strongly in the Cornell Woolrich vein, as darkishly noir as you might want, and in some regards the writing is better than Woolrich’s. Full of strong imagery in the telling, there’s also more than a hint of humor, more than I remember in Woolrich’s.

Of course it’s also time for me to go back and re-read all of Woolrich’s work. It’s been far too long, but in the meantime this singular book by Geoffrey Hall will more than do. I’ve also just discovered that, unknown to Al Hubin, a film has been made from The End Is Known, as an Italian-French co-production called La fine è nota (1993). One comment has been left, so a viewable copy must exist somewhere, and I’d love to be able to see it, wishing as I say that that I also understood Italian.

The title comes from Julius Caesar (the play), in which Brutus at one point says “O, that a man might know / The end of this day’s business ere it come! / But it sufficeth the day will end / And then the end is known.”

Here’s the set-up: As department store vice-president Bayard Paulton makes his way home from work one evening, he is nearly hit by a man falling to his death from an upper story window. The apartment the man came from was his own, remarkably enough, and even more remarkably, Paulton does not know the man.

According to Mrs. Paulton, the man, also unknown to her, came to see her husband, who was delayed and not yet home, and after a few minutes of pacing while he waited, before she realized his intentions, he opened a window and leaped out.

From page 13: “All that occurred to him in that moment, all that he could rember with certainty afterward, was a sentence he had read years before in a novel he had since fogotten. ‘The body fell crazily, and landed askew, like a rag doll.’ And he thought, watching what happened, that was exactly how it looked.”

Thus the other reason for the title. The man’s end is known. Bayard’s mind is quickly taken over by the mystery? Who was he? Why did he tell his wife “Your husband is the only man who can help me?” But then why didn’t he wait for Bayard Paulton to arrive home?

What follows is Bayard’s attempt to trace the man’s life backward and then forward again to learn the answers to these questions and others.

The police, in the form of Lt. Wilson, are interested, but after the body is claimed by an eccentric woman from Montana, who tells them that she only knew him for a few months herself while he was working for her in her diner, they (the police) have other more important things they need to be doing.

The bulk of the book is therefore both fascinating and very talky. Bayard takes out newspaper ads to find people who may have known the dead man, and remarkably enough, he gets responses.

He learns a lot, but not enough to answer his questions. On page 143, he is back in his apartment, alone in his thoughts:

If only, Bayard Paulton thought, I had come home five minutes earlier…

On page 173, as Paulton gets closer to the truth, if you don’t mind reading so many quotes, but I do want you to know why I call this a minor unknown classic of noir fiction:

Bayard Paulton did not speak. He did not, even, stir in his uncomfortable chair. Because Jesse Dermond’s features, her whole body, were too markedly revealing. They showed pain and sorrow and an incomprehension of the things that life could do to you.

Any novel which begins at the ending, with a death that was inevitable, the final straw in a life of dreams, and the futility of those dreams, has to be noir. For this reason, among those I have already mentioned, as well as still others that I am respectfully refraining from passing along to you, I recommend this book highly.