SCORPIO ROOMS: VICTOR CANNING ON TV

by Tise Vahimagi

From flash to futile: the Spy/Espionage genre in 1960s cinema and television. Seldom could a vogue have sprung so quickly from so little, and progressed so hurriedly from fresh beginnings to extravagant decadence and self-parody.

Fortunately, for television at least, Victor Canning was one of those astute writers who was all too aware of the genre’s doomed direction and managed to maintain a masterly hand in its various manifestations with dexterity and with dignity.

Recent re-examination of his TV career has revealed an astonishingly prolific contributor to the small screen. For devotees of Canning’s work, the 1960s must have been pure bliss. Various single plays, a sequence of multi-part serials, forays into episodic drama, each with its own particular flavour of veiled menace and sinister associations.

Earlier TV credits had largely been adaptations of his short stories, more often in the tenor of the safe than the surprising: “Never Trust a Lady” (CBS, 1953), with Marcel Dalio as a silky gentleman burglar; “A Thief There Was” (CBS, 1956), the misadventure of a jewel thief; “Disappearing Trick” (CBS, 1958), the comeuppance of a blackmailer; “Man on a Bicycle” (CBS, 1959), with Fred Astaire as a likeable con-man; and “Girl in the Gold Bathtub” (CBS, 1960), a gentle yarn about an American ad agency man sent to Italy to retrieve the title combination.

His 1960s quintet of serialised dramas, however, belong not so much to the espionage or the thriller form as to a new kind of anxiety fantasy, with their brooding heroes nursing neurotic doubts about their predicament.

The first, The Midnight Men (BBC, 1964), was set in 1913 and featured a foolhardy Andrew Keir as a crack-shot recruit in an assassination plot to kill a king in a Balkan state.

A rescue thriller (with shades of The 39 Steps) formed the basis of Curtain of Fear (BBC, 1964) in which a cabaret performer, Miss Memory, is kidnapped while under hypnosis and carrying state secrets in her extraordinary memory (which sounds uncannily similar to his later novel Memory Boy, 1981); George Baker was the perplexed fiancé in pursuit, dodging various British and Russian agents.

Contract to Kill (BBC, 1965) returned to an Ambleresque milieu with a Frenchwoman seeking revenge on a Nazi for the murder of her son during the war, a German secret society pledged to aid ex-Nazis on the run, and with freelance agent Jeremy Kemp embroiled in the murky activities.

Taking the form of a more conventional thriller, Breaking Point (BBC, 1966) tells of a metallurgist who has discovered a form of steel which is immune to metal fatigue, and the security agent assigned to protect him and his discovery from hostile international interests. The suspense of imminent discovery sustained This Way for Murder (BBC, 1967), involving a sinister corporate crime structure and its infiltration by reformed ex-crook Terence Longdon on behalf of British police.

It was somewhat disheartening to learn that (save an episode or two, and with only This Way for Murder remaining complete) all the above BBC serials have been junked.

More straightforward crime elements — the TV plays about diamond thieves in Miracle on Mano (ITV, 1962) and Double Stakes (ITV, 1963), blackmail in Come Into My Parlour (ITV, 1965), working admirably in terms of involvement and suspense — were woven into stories for BBC’s Paul Temple (1969-71) and the suspense anthology The Man Outside (1972), adding an understated, realistic quality.

Surprisingly, there was even a two-part Mannix story in 1975 (scripted by Alfred Hayes) based on his 1951 novel Venetian Bird.

The chill awareness of a lethal cloak-and-dagger world, however, couldn’t help but surface in the conspiracy-obsessed British Intelligence agent series The Rat Catchers (ITV, 1966-67) for which Canning composed two three-part stories, cheerfully spreading characters and plot across various European locales.

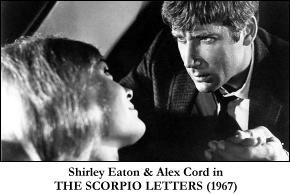

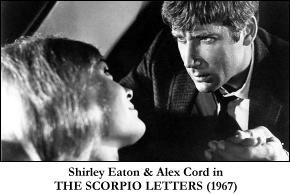

The MGM TV film The Scorpio Letters (ABC, 1967) arrived somewhere between talkative mystery and uneventful spy thriller. Alex Cord’s laconic, mildly sardonic agent hero and the film’s underlying theme about the corrupting effect of temporarily-acceptable violence in wartime failed to stimulate the main plot: the discovery of the elusive blackmailer Scorpio.

The always-interesting Man in a Suitcase (ITV, 1967-68), often entangled in its own conspiracies, produced the absurdly compelling “Blind Spot” in which Canning had Richard Bradford’s usually impassive McGill warm to a blind girl he is protecting as a ‘witness’ to a murder.

The counter-spy series Codename (BBC, 1969-70), about a British spy cell which uses a university as its cover, also called on Canning for a story, allowing him further exploration of the cool and brutal sophistication about Intelligence procedure, and its extreme ingenuity as a mechanism.

For the completists, there is also a German made-for-TV film, Das ganz grosse Ding, produced in 1965, but I have been unable to determine the original Canning story source.

Some modern references suggest Canning appeared as an actor in a 1967 episode (“The Mercenary”) of BBC police series Dixon of Dock Green. On consulting BBC TV Broadcast Programme information (a record of actual BBC transmission details) for this particular episode, I found that although there is no Victor Canning given in the cast list there is an actor called Victor Winding playing ‘Ben Chambers’. Perhaps this soundalike name was the source of the confusion…?

Victor Canning Television:

1. “Never Trust a Lady” / Your Jeweler’s Showcase (CBS, 9 June 1953). Dir: Ralph Murphy. Scr: Howard J. Green, adapted by Frank L. Moss; from original story by Canning. Cast: Marcel Dalio, Ray Teal, June Vincent.

2. “A Thief There Was” / Appointment With Adventure (CBS, 18 Mar 1956). Dir: Paul Stanley. Scr: Victor Canning, from story by Abby Mann. Cast: Christopher Plummer, Jason Robards, Constance Ford.

3. “Disappearing Trick” / Alfred Hitchcock Presents (CBS, 6 Apr 1958). Dir: Arthur Hiller. Scr: Kathleen Hite, based on s.s. by Canning [UK ed. Argosy, Sept 1957]. Cast: Robert Horton, Betsy von Furstenberg, Perry Lopez.

4. “Man on a Bicycle” / General Electric Theatre (CBS, 11 Jan 1959). Dir: Herschel Daugherty. Scr: Jameson Brewer, from short story “Young Man on a Bicycle [Cosmopolitan, Oct 1955]. Cast: Fred Astaire, Roxane Berard, Stanley Adams.

5. “Girl in the Gold Bathtub” / The U.S. Steel Hour (CBS, 4 May 1960). Dir: Allen Reisner. Scr: Robert Van Scoyk, from [original?] story by Canning. Cast: Marisa Pavan, Jessie Royce Landis Edward Andrews, Johnny Carson.

6. “Miracle on Mano” / Play of the Week (ITV, 14 Aug 1962). Dir: John Hale. Scr: VC. Cast: Patrick Magee, Derek Francis, Alan Tilvern.

7. “Double Stakes” / Play of the Week (ITV, 7 May 1963). Dir: John Hale. Scr: VC. Cast: Nigel Davenport, Jane Hylton, Richard Shaw.

8. The Midnight Men (serial; BBC, 21 June-26 July 1964; 6 x half-hour). Prod/Dir: Rudolph Cartier. Scr: VC. Cast: Laurence Payne, Andrew Keir, Derek Francis, Eva Bartok.

9. Curtain of Fear (serial; BBC, 28 Oct-2 Dec 1964; 6 x half-hour). Prod/Dir: Gerald Blake. Scr: VC. Cast: Colette Wilde, George Baker, John Breslin, William Franklyn.

10. Contract to Kill (serial; BBC, 3 May-7 June 1965; 6 x 25 mins). Prod: Alan Bromly. Dir: Peter Hammond. Scr: VC. Cast: Jeremy Kemp, Pauline Bott, Ronald Radd.

11. “Come Into My Parlour” / Suspense Hour (ITV, 11 July 1965). Dir: John Cooper. Scr: VC. Cast: Keith Barron, Renny Lister, Ray Barrett.

12. “Operation Lost Souls” / The Rat Catchers (ITV, 13 Apr 1966). Dir: Bill Hitchcock. Scr: VC. Regular Cast: Glyn Owen, Gerald Flood, Philip Stone; Tom Watson, Bernard Kay, Sally Home.

13. “Operation Irish Triangle” / The Rat Catchers (ITV, 20 Apr 1966). Dir: Bill Hitchcock. Scr: VC. Regular Cast [as above]; Eugene Deckers, Rachel Gurney, Patricia Haines.

14. “Operation Big Fish” / The Rat Catchers (ITV, 27 Apr 1966). Dir: Bill Hitchcock. Scr: VC. Regular Cast [as above]; Eugene Deckers, Rachel Gurney, Alan Gifford.

15. Breaking Point (serial; BBC, 22 Oct-19 Nov 1966; 5 x 25 mins). Prod: Alan Bromly. Dir: Douglas Camfield. Scr: VC. Cast: William Russell, Rosemary Nicols, Richard Hurndall.

16. “Mission to Madeira” / The Rat Catchers (ITV, 22 Dec 1966). Dir: Don Gale. Scr: VC. Regular Cast [as above]; John Abineri, Hannah Gordon, Richard Warner.

17. “Death in Madeira” / The Rat Catchers (ITV, 5 Jan 1967). Dir: Don Gale. Scr: VC. Regular Cast [as above]; Frederick Treves, Hannah Gordon, Susan Engel.

18. “Midnight Over Madeira” / The Rat Catchers (ITV, 12 Jan 1967). Dir: Don Gale. Scr: VC. Regular Cast [as above]; Frederick Treves, Susan Engel, John Abineri.

19. The Scorpio Letters (TV film; ABC, 19 Feb 1967). Dir: Richard Thorpe. Scr: Adrian Spies, from 1964 novel. Cast: Alex Cord, Shirley Eaton, Laurence Naismith, Oscar Beregi. [Cinema release in UK in May 1968]

20. This Way for Murder (serial; BBC, 3 June-8 July 1967; 6 x 25 mins). Prod: Alan Bromly. Dir: Eric Hills. Scr: VC. Cast: Hugh Cross, Terence Longdon, Isobel Black.

21. “Blind Spot” / Man in a Suitcase (ITV London, 10 Feb 1968). Dir: Jeremy Summers. Scr: VC. Cast: Richard Bradford, Marius Goring, Felicity Kendall.

22. “The Alpha Man” / Codename (BBC, 9 June 1970). Dir: Ronald Wilson. Scr: VC. Cast: Clifford Evans, Anthony Valentine, Alexandra Bastedo.

23. “With Friends Like You, Who Needs Enemies?” / Paul Temple (BBC, 30 June 1971). Dir: Michael Ferguson. Scr: VC. Cast: Francis Matthews (Paul Temple), Ros Drinkwater (Steve), George Sewell.

24. “Cuculus Canorus” / The Man Outside (BBC, 16 June 1972). Dir: Raymond Menmuir. Scr: VC. Cast: Rupert Davies (intro); Anthony Hopkins, Gerald Flood, Michael Gambon.

25. “Never Trust a Lady” / Of Men and Women (TV special; ABC, 6 May 1973). Dir: Lee Phillips. Scr: Harry Musheim, from Canning’s story. Cast: Jack Cassidy, Barbara Feldon, Mary Jackson.

26. “Bird of Prey” (two-part episode) / Mannix (CBS, 2 & 9 Mar 1975). Dir: Michael O’Herlihy. Scr: Alfred Hayes, based on the 1951 novel Venetian Bird. Cast: Mike Connors, Richard Evans, Robert Loggia.

27. The Runaways (TV film; CBS, 1 Apr 1975). Dir: Harry Harris. Scr: John McGreevey, from 1972 novel. Cast: Dorothy McGuire, Van Williams, John Randolph, Neva Patterson.