CLYDE B. CLASON – Murder Gone Minoan

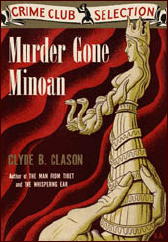

Rue Morgue Press; trade paperback, 2003. Original hardcover edition: Doubleday Crime Club, 1939. Hardcover reprint: Sun Dial Press, 1940.

Checking on www.abebooks.com just a few minutes ago, I found only one copy of the Crime Club edition for sale: Near Fine in a Near Fine jacket. Price: a mere $250.00. Further searching revealed a few other copies on other venues, one being a former library copy with no jacket. Price: a much more reasonable $35.00.

But if $14.95 is all you want to spend, this handsome trade paperback will do very nicely. This is but one of many classic mystery reprints coming from Tom & Enid Schantz of Rue Morgue Press, and they should be commended for a job well done, and for jobs yet to be done. (At the moment, the only other Clason title they’re published is The Man from Tibet, but perhaps others are on their way. Only sales will tell, I imagine.)

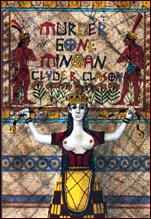

Only one thing is lacking, before I continue, and that is the original cover art, which as I recall was by Boris Artzybasheff. That gentleman no longer being available (or affordable) a fine piece of work by Rob Pudim was used in his stead. To my eye it’s a bit cluttered, but it Does Catch the Eye.

Clason’s series detective is an eminent Roman historian named Theocritus Lucius Westborough — Westborough for short — who also has earned a well-deserved reputation as a private investigator on the side. If this book is an example — which from my point of view it has to be, at least for the moment, since if I ever read an earlier book in the series, it was long ago and long forgotten — Westborough’s adventures are copiously filled with well-researched lore of ancient times, interspersed with mini-lectures on the same.

I’m jumping the gun here, but it’s Westborough’s knowledge of ancient history that helps crack a killer’s alibi — which is not quite fair to the reader not recently tutored in such matters — such as myself, I have to admit — but it’s a sizable step above nabbing a villain who reveals himself because he’s not aware that buildings do not have thirteenth floors, for example.

Just in passing. There is a deliberate misstatement on my part that is not quite correct in the last sentence of the previous paragraph, but if I were to speak more clearly, I would be revealing more of what Clason had up his sleeve than I should.

This, the seventh of ten cases Westborough is on record as having solved, takes place on an isolated island off the southern California shore, where first a valuable artifact is stolen — and Westborough called in — and then murder, when a missing butler is later found dead.

The owner of the island, a rich Greek businessman named Paphlagloss, is fascinated with the ancient Minoan culture, pre-historic Cretans whose civilization arose and fell even before the ancient Greeks, and his mansion is filled with valuable relics, artwork and jewels.

It is just the right place for skulduggery to be done, and with only a handful of suspects, one of whom is responsible for doing the dugging, it’s a perfect setting for a mystery.

Another of Clason’s strengths is in his characters and their dialogue. To my ears, the lengthy reports of letters and verbatim interviews of suspects are close to perfect. Other parts of the tale are excellent, while others, contrarily, are pure fuddle-muddle.

I like the following quote, for some reason, taken from pages 160-161. Paphlagloss’s daughter is having a private conversation with Westborough:

She shivered and drew the wrap closely to her slim body. “Why do things have to be in such a perfect devil of a mess?”

His mild eyes peered distressfully through his gold-rimmed spectacles. “The question, I should conjecture, has been propounded rather frequently during the four thousand years of recorded history. However, I am unable to recall a single instance where it was answered satisfactorily.”

“You are very wise!” she exclaimed.

He shrugged deprecatorily. “My wisdom is confined to a single fact. I have lived long enough to learn that most of my fellow creatures — and myself, as well — must of necessity be a little foolish.”

“What would you advise me to do?”

“I dare not advise you, my dear. The situation is too delicate. As delicate,” he added thoughtfully, “as the ripples of a Chinese nocturne.”

While it’s great to have this small gem of the Golden Age of Mysteries back again in print, I also have to suggest that it didn’t then, and it doesn’t now, have the staying power of one by a Queen, a Christie, or a John Dickson Carr.

Even so, and within its limitations, Murder Gone Minoan is a gem in its own right, and no, they don’t write them like this anymore.

— January 2004

[UPDATE] 07-16-09. Rue Morgue Press has now published four of the ten Clason-Westborough mysteries: Dragon’s Cave, Green Shiver, Murder Gone Minoan, and Poison Jasmine. I don’t know whether the fact that these are also the last four is significant or not. I’d like to think that they’d eventually do all ten.