BILL PRONZINI on WILLIAM CAMPBELL GAULT:

William Campbell Gault was a writer of the old school, a consummate professional throughout a distinguished career that spanned more than half a century. From 1936 to 1995 he published scores of novels, both mysteries and juvenile sports fiction and hundreds of short stories, and counted among his awards an Edgar from the Mystery Writers of America, and the Life Achievement Award from the, Private Eye Writers of America.

Noted author and critic Anthony Boucher said of him: “(He is) a fresh voice — a writer who sounds like nobody else, who has ideas of his own ,and his own way of uttering them.” Another of his peers, Dorothy B. Hughes, stated that he “writes with passion, beauty, and with an ineffable sadness which has been previously been found only in Raymond Chandler.”

He was in his mid-20s when he entered a story called “Inadequate” in a Milwaukee Journal-McClure Newspaper Syndicate short story contest. The judges found it to be anything but inadequate, awarding it the $50 first prize. Spurred on by this success, he wrote and placed several more stories with the McClure Syndicate, then in 1937 entered the wide-open pulp field with the sale of a drag-racing story, “Hell Driver’s Partnership,” to Ace Sports.

Over the next fifteen years he was a prolific provider of mystery, detection, sports, both light and racy romance, and science fiction to such pulps as 10-Story Detective (where his first criminous story, “Crime Collection,” appeared in January of 1940), Detective Fiction Weekly, The Shadow, Clues, All-American Football, Strange Detective Mysteries, Adventure, Dime Mystery, Dime Detective, Doc Savage, Argosy, Detective Tales, Five Novels Monthly, and Thrilling Wonder and to such “slick” and specialty magazines as The Saturday Evening Post, Grit, and McClure’s.

In the late forties he was featured on the covers of the king of the detective magazines, Black Mask, in whose pages he published nine stories, five of them featuring an offbeat, Duesenberg-driving private detective named Mortimer Jones.

When the pulp markets collapsed in the early fifties, Gault turned his hand to book-length works. He published the first of his 33 novels for young readers, Thunder Road, in 1952, a work which stayed in print for more than three decades. Appearing that same year was his first mystery, Don’t Cry for Me, one of the seminal crime novels of its time.

Prior to Don’t Cry for Me, the emphasis in mystery fiction was on its whodunit / whydunit aspects. Gault’s novel broke new ground in that its whodunit elements are subordinate to the personal lives of its major characters and to a razor-sharp depiction of the socioeconomic aspects of its era — an accepted and widely practiced approach utilized by many of today’s best writers in the field.

His fellow crime novelist, Fredric Brown, said of the novel: “[It] is not only a beautiful chunk of story but, refreshingly, it’s about people instead of characters, people so real and vivid that you’ll think you know them personally. Even more important, this boy Gault can write, never badly and sometimes like an angel.”

The Mystery Writers of America agreed, voting Don’t Cry for Me a Best First Novel Edgar. Gault’s subsequent mysteries are likewise novels of character and social commentary, whether featuring average individuals or professional detectives as protagonists.

Many have unusual and/or sports backgrounds, in particular his non-series works. The Bloody Bokhara (1952) deals with the selling of valuable Oriental rugs and carpets in his native Milwaukee; Blood on the Boards (1953) has a little-theater setting in the Los Angeles area; The Canvas Coffin (1953) concerns the fight game and is narrated by a middleweight champion boxer; Fair Prey (1956, as by Will Duke) has a golfing background; Death Out of Focus (1959) is about Hollywood filmmakers and script writers, told from an insider’s point of the-view.

An entirely different and powerful take on the Hollywood grist mill is the subject matter of his only mainstream novel, Man Alone, written in 1957 but not published until shortly before his death in 1995.

The bulk of Gault’s 31 criminous novels — and many of his short stories showcase series detectives. One of the first was Mortimer Jones, in the pages of Black Mask; another pulp creation, Honolulu private eye Sandy McKane, debuted in Thrilling Detective in 1947.

Italian P.I. Joe Puma, who operates out of Los Angeles, was created for the paperback original market in the fifties, first as the narrator of a pseudonymous novel, Shakedown (1953, as by Roney Scott), and then of several books published under Gault’s own name between 1958 and 1961, notably Night Lady and The Hundred-Dollar Girl.

His last and most successful fictional detective was Brock “The Rock” Callahan, an ex-L.A. Rams lineman turned private eye, who first appeared in Ring Around Rosa in 1955. Callahan, along with his lady friend, interior decorator Jan Bonnet, did duty in six novels over the next eight years. In a rave review of Day of the Ram (1956), The New York Times called Callahan “surely one of the major private detectives created in American fiction since Chandler’s Phillip Marlowe.”

After the publication of Dead Hero in 1963, Gault abandoned detective fiction to concentrate on the more lucrative juvenile market. It was nearly twenty years before he returned to the mystery field; and when he did return, it was exclusively with stories of an older, wiser, married (to Jan Bonnet), inheritance-wealthy, and semi-retired Brock Callahan.

The new series of Callahan books began with The Bad Samaritan (1982); six others followed, culminating with Dead Pigeon in 1992. In The Cana Diversion (1982) Gault also brought back Joe Puma — dead. The novel’s central premise is Puma’s murder and Callahan’s search for the killer, a tour de force that earned a Private Eye Writers of America Shamus for Best Paperback Original.

The hallmarks of Bill Gault’s fiction are finely tuned dialogue, wry humor, sharp social observation, a vivid evocation of both upper class and bottom-feeder lifestyles, and most importantly, the portrayal of people, in Fredric Brown’s words, so real and vivid that you’ll think you know them personally.

— This essay first appeared as the introduction to The Marksman and Other Stories, by William Campbell Gault and edited by Bill Pronzini (Crippen & Landru, hardcover, March 2003). Reprinted with the permission of Bill Pronzini.

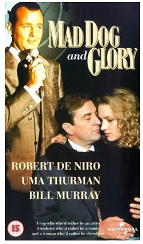

MAD DOG AND GLORY. Universal Pictures, 1993. Robert De Niro, Uma Thurman, Bill Murray, David Caruso, Mike Starr, Kathy Baker. Screenwriter: Richard Price; director: John McNaughton.

MAD DOG AND GLORY. Universal Pictures, 1993. Robert De Niro, Uma Thurman, Bill Murray, David Caruso, Mike Starr, Kathy Baker. Screenwriter: Richard Price; director: John McNaughton.