Fri 29 Aug 2008

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS review: JAMES M. CAIN – The Postman Always Rings Twice.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Authors , Reviews[2] Comments

JAMES M. CAIN – The Postman Always Rings Twice.

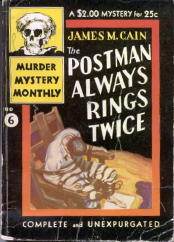

Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1934. Paperback reprints include: Avon Murder Mystery Monthly #6, 1943; Pocket 443, 1947; Bantam, 1967; Vintage, 1978.

Films: 1946, with Lana Turner & John Garfield; 1981, with Jessica Lange & Jack Nicholson.

This brutal little blue-collar love story was a shocking, sexy, “dirty” best seller and set the standard for tough, lean writing. It taught readers (and writers) that dialogue could propel a story by its own steam (and steaminess) with (as Cain himself put it) “a minimum of he-saids and she-replied-laughinglys.”

From its famous first sentence (“They threw me off the hay truck at noon”) to its spellbinding final moments on death row, The Postman Always Rings Twice moves like a freight train, catching the reader up in a sleazy, unpleasant – and compelling – illicit love affair.

Drifter Frank Chambers. finds himself in a roadside eatery called Twin Oaks Tavern (the first of many double images). Nick Papadakis, the friendly Greek who runs the place, has a wife who “really wasn’t any raving beauty, but she had a sulky look to her.”

Soon Chambers is running the tavern’s gas station for the Greek; and by the end of chapter two, Frank and Cora have made a cuckold of him; by chapter four they are attempting Nick’s murder. And these are short chapters.

Incredibly, the adulterers engage not just our interest but our sympathy, our collusion. Their lust (“I sunk my teeth into her lips so deep I could feel the blood spurt into my mouth”) is contagious, and redeemed by the extravagance of their passion (“I kissed her … it was like being in church”).

Yet Cain pulls no punches: Their intended murder victim, Nick, is not unsympathetic; Frank genuinely likes Nick, and after Frank and Cora succeed on the second try and kill him, cries genuine tears at his funeral.

Frank and Cora – particularly Frank – are so out of control, so much smaller than the web of circumstance and human frailty in which they are caught up, that a strange sort of supportive interest develops for them. Cain feels for these small lovers who are doomed in so big a way.

And so do we. When in the aftermath of Nick’s murder and the faked auto accident that follows, Cora and Frank indulge in a manic orgy of sadomasochism and passion at the scene of the crime, we are caught up in the moment with them. As Frank says: “Hell could have opened up for me then, and it wouldn’t have made any difference. I had to have her, if I hung for it.”

Part of the enduring power of Postman is its evocation of the depression. Frank and Cora’s dream is the American one: They want a business of their own, a family of their own-simple goals that had been made so difficult in hard times. Their greed was small; their aspirations petty. Their love, and their crime, in James Cain’s tabloid opera, large.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.