Wed 16 Sep 2009

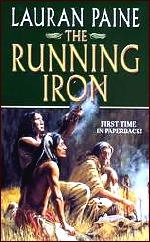

Archived Western Review: LAURAN PAINE – The Running Iron.

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Western Fiction[5] Comments

LAURAN PAINE – The Running Iron.

Five Star, hardcover; first edition, November 2000. Leisure, paperback reprint; 1st printing, April 2002.

Lauran Paine isn’t a household name, but over the past 50 years he’s been a small powerhouse in the world of traditional westerns. His overall output, including mysteries and romances, includes over 1000 books published, many only in England, under nearly 100 pseudonyms.

One difference between Paine and his younger contemporaries is that he’s lived closer to the time period he writes about, rather than learning about it second-hand. The characters in his stories are taciturn and close-mouthed. They don’t feel obliged to talk about what they’re thinking, what they’re doing or why. Newer writers seem to explain everything. Paine shows and often doesn’t tell.

In this story, after Old Joe Jessup dies, his ranch is left to May, his Indian wife, and his adopted son, Little Joe. A neighboring rancher wouldn’t mind adding the land to his own spread. Can one boy, an old woman, and an even more ancient hired hand manage to hold on without him?

In close conjunction to this, the army is called in to move a small tribe of Indians, May’s extended family, onto a reservation. In terms of action, there’s very little. Each chapter moves six inches forward, then five to ten inches back. The end result is a book that’s both frustrating and captivating.

[UPDATE] 09-16-09. This review appeared for the first time in a newsletter for the Historical Novel Society soon after the hardcover came out, and before Lauran Paine died in 2001. As I noted above, I reprinted it later in my western fiction apazine, where I didn’t do any rewriting, nor have I now.

Some of the names Paine wrote under, besides his own, are (take a deep breath) John Armour, Reg Batchelor, Kenneth Bedford, Frank Bosworth, Mark Carrel, Robert Clarke, Richard Dana, J F Drexler, Troy Howard, Jared Ingersol, John Kilgore, Hunter Liggett, J K Lucas, and John Morgan.

I haven’t done any counting, so I don’t know if the list of titles is complete at either Web location — there certainly doesn’t seem to be over a few hundred at either one — but at least you can find partial bibliographies on Wikipedia and the Fantastic Fiction site, the latter with many covers.