THE THING IN THE NYMPH,

by David L. Vineyard

“The Wizard’s Belt” by T. P. HANSHEW, from Cleek, the Master Detective. Doubleday, US, hardcover, 1918. Originally published in the UK as The Man of the Forty Faces (Cassell, hc, 1910).

In relation to Hanshew and Cleek I’ve previously mentioned [Comment #2] a story that I thought might have inspired one of Dorothy L. Sayers more bizarre and memorable Lord Peter Wimsey short stories: “The Abominable History of the Man with Copper Fingers” in Lord Peter Views the Body. “The Wizard’s Belt,” the sixth story in the twelve story collection Cleek, the Master Detective is that story.

As was common in that era, the book is what science fiction fans used to call a ‘fix-up,’ meaning related short stories that more or less form a novel narrative. This one features Hamilton Cleek, formerly the “Vanishing Cracksman,” and the one time king of Maurivania (he still lives of in fear of assassins and the agents of the French criminal underground known as the Apaches), a master of disguise (the Man of Forty Faces — apparently he was no Lon Chaney), and now a consulting detective for Scotland Yard, and his friend Mr. Maverick Narkom.

Since there is no possible way to discuss this story without giving away major elements, here is a

As the story opens, Narkom has contacted Cleek about a curious mystery that has arisen and the plight of a young woman and her invalid father, a couple of modest means. It seems her beau has disappeared from his room at their house with no trace. During an evening’s entertainment attended by the young lady, Miss Mary Morrison and her father Captain Morrison, the fiance George Carboys, and an artist friend Van Nant, Carboys began to talk about his days in the far east and the fortune owed Carboys by a wealthy Easterner who never gave him anything but some worthless trinkets — among them a blue leather belt claimed to have the power of invisibility.

Carboys then donned the belt, and still wearing it went to bed. The next morning he was not to be found. The belt lay on the floor in the locked room, and Carboys has vanished without a trace.

“Necromancy — wizardry — fairy lore — all the stuff and nonsense that goes into the making of ‘The Arabian Nights’ … All your ‘Red Crawls’ and your ‘Sacred Sons’ and your ‘Nine-fingered skeletons’ are fools to it for wonder and mystery. Talk about witchcraft! Talk about wizards, and giants, and enchanters and the things that the witches did in MacBeth! God bless my soul they’re nothing to it …”

Obviously Narkom is impressed. Cleek less so, to give him credit. But he takes the case and goes to investigate under the guise of George Headland. Once at the Morrisons he learns Carboys had an important meeting with a solicitor the next morning, and examines the man’s room.

In rather good minor Holmes style he quickly dismisses the obvious. “Our wonderful wizard does not seem to have mastered the simple matter of making a man vanish out of the thing, without first unbuckling the belt,” Cleek opines, and then goes on to point out that the belt is English and American, not from the Middle East, that Carboys had shaved, but not undressed, and obviously went out again unseen.

Still he has vanished. The sharp eyed Cleek also see Miss Morrison keeps pigeons, and notes some strange about one of the birds.

His investigation then takes him to Van Nant’s studio where he discovers among other things a statue of a Roman Senator, and a large rather ugly and misshapen figure of a nymph recently carved, and showing no signs of Van Nant’s talents. “My touch seems to have deserted me. Temporarily I hope.”

At this point Cleek announces he is baffled and can only hope to consult a clairvoyant. He arranges for Narkom to have the Morrisons and Van Nant meet at the Morrison’s house the next night, where no one less than the famous Hamilton Cleek will show up to solve the case.

But when Cleek doesn’t show, Narkom tells the others that Cleek is going to visit Van Nant’s studio before coming to the Morrison home. Van Nant feels he should be at home to meet Cleek, even though Cleek wouldn’t need to key to get in, and leaves. He arrives at his studio, calls out for Cleek though there is no answer, and goes directly to the ugly half-formed figure of the nymph.

At which point the statue of the Roman Senator pounces on him, wrestles him to the ground, and snaps on the cuffs. As Cleek, disguised as the statue, announces his arrest Narkom and the police burst in. They take the prisoner, and Cleek takes a hammer to the statue of the nymph — revealing the body of George Carboys inside.

It seems Carboys’ old friend the Eastern potentate had died and left a considerable fortune to Carboys. Van Nant knew, and since there was an old will naming him Carboys heir, that would be invalid when Carboys married Miss Morrison, he lured Carboys to his studio by making him think Miss Morrison was his secret lover, murdered him, and encased the body in the modeling clay.

He might have gotten away with it too if Cleek hadn’t seen a speck of clay on one Miss Morrison’s pigeons, the one Van Nant used to plant the note luring Carboys to his studio to be murdered… The note, allegedly from Miss Morrison, is found in Carboy’s pocket.

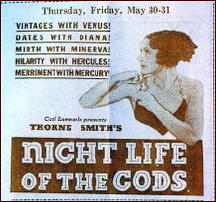

Hanshew must have liked the idea because he used it before in one of the stories in Cleek of Scotland Yard (1914) in a story involving another locked room — this one made of glass — a missing boy, and a waxworks. Of course it was also the plot of the film Murder in the Wax Museum and its remake, House of Wax. I seem to recall it even happened in reality once, but that may be an urban myth like poodles and microwave ovens.

You can see why John Dickson Carr was a fan of Cleek other than Hanshew being another American expatriate living and writing in England. For sheer melodrama and weird crime Cleek can be hard to beat. Quite a few locked rooms and impossible crimes occur, though they might be less mysterious if Maverick Narkom wasn’t prone to exaggeration, melodramatic statements, and hyperbole.

But then what can you expect from someone who thinks it is the height of discretion to pick the mysterious and secretive Cleek up in a red limousine.

Some of the stories are more preposterous than this, but almost all are fun, and Cleek has some of the true Holmes style as well as some of the traits of later pulp heroes like The Shadow or Phantom Detective. True, most of his big revelations are pretty obvious, and Holmes could have solved them with half a cigarette — no three pipe problems here — and some do fall into the category of Raymond Chandler’s famous critique of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express — only a moron could have solved it.

Hanshew mostly walks a fine line between genuine mystery stories and pure claptrap, but he does walk it, and even when he misses a step the result is interesting. The writing does suffer a bit from some of the flaws of the era — a touch of what American writer and critic John Gardner called the Pollyanna school of writing, but for the most part Hanshew and Cleek are entertaining — even when laying it on a bit thick.

Of course there is no evidence Dorothy L. Sayers read this story or borrowed from it, but there are certain similarities. Her own story is better and builds to a nice chill at the end, but the Hanshew tale has its charms, and is accompanied by a nice illustration by Gordon Grant.

And whether the story inspired Sayers or not, it is one of the better Cleek tales, pardoning the melodrama and high handedness. Overall a good tale in a fairly good collection of one of the more interesting writers and creations of the period.

Still, I’ve always wondered why only forty faces? Maybe that was Hanshew-the-actor’s own limits. Surely he must have imagined himself playing his creation on stage. Even Conan Doyle never got to be Sherlock Holmes in the theater. Maybe forty faces was all he thought he could handle.

Editorial Comment: Besides David’s previous comments about Thomas Hanshew on this blog (follow the link in the first paragraph above), Mike Grost reviewed Cleek, Master Detective in its entirety in this followup post.