Sun 23 Apr 2023

A Book! Movie!! Review by Tony Baer: SHERWOOD KING – If I Die Before I Wake // The Lady from Shanghai (1947).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[7] Comments

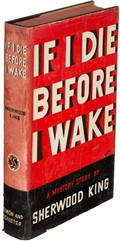

SHERWOOD KING – If I Die Before I Wake. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 1938. Mystery Novel Of The Month [no number], digest-sized paperback, 1940. Ace Double D-9, paperback, 1953. Curtis, paperback, 1965. Penguin Classic, softcover, 2010. Film: Columbia, 1947, as The Lady from Shanghai. (Rita Hayworth, Orson Welles, who also directed).

Another from James Sandoe’s hardboiled checklist , this novel formed the basis of the Orson Welles film The Lady from Shanghai, which is one of my favorite noirs.

The experience of reading the novel was similar to reading In a Lonely Place after seeing Nicholas Ray’s great film. That is to say, there’s a strange cognitive dissonance. The film is so vividly done that it stays with you. And now you read a story with the same characters in the same time and place, and they act completely differently, resulting in a starkly different experience. It’s weird. Rifted from one universe into another like a car crash jettisoning you out the window, shards shattering, thrusting you through the looking glass.

It makes it hard for me to judge the book without a bit of resentment. And the resentment is utterly unfair because the book came first. But the images of the film are so entrenched that I simply cannot accept the story presented by the book.

First of all, the first person protagonist is named Laurence Planter — not Michael O’Hara. Though in both he’s a sailor. In the film Orson Welles gives us a robustly distracting Irish brogue. Planter is no more Irish than Welles. So the choice to turn Planter to O’Hara is pretty odd. Welles must have just wanted an opportunity to show his range or something. There’s very little background so his nationality is irrelevant to the narrative.

Planter gets sucked into the lavishly unseemly seaminess of Mr. and Mrs. Bannister. In the film he enters rescuing Mrs. Bannister from Central Park muggers. In the book, he’s hired as Chauffeur on the spot when Mr. Bannister spies him swimming up to their Long Island shore. Marvelous tanned physique in tow.

Mr. Bannister’s stuttered gait (in both film and book) is horribly maimed lame by a wartime missile. This causes Bannister to be forever angry at his loss of youth, and at those that have it and don’t appreciate it. They die before they wake.

Bannister leverages his disability into guilt subjecting his wife Elsa into a life of sad subjection. Without objection. And yet Bannister wants to tempt his wife and to spy upon her, looking and luring her with opportunity for alienated affections, the better to guilt her with and rail upon her for her rancid heart. Planter/O’Hara was drawn up by central casting as the perfect lure. Handsome, winsome, and nitwit.

Bannister is a great criminal defense attorney, as is his law partner Grisby. Grisby hires our fair sailor for a dirty deed. Grisby wants to disappear. He wants our sailor to pretend, in plain sight, to murder him and pretend to throw his body into the sea. Corpus delicti — without the body you can prove no crime. Meanwhile Grisby will escape safe to sea, via speedboat, presumed dead — while our sailor cannot be held to blame. And five grand the richer for really doing nothing wrong.

But Grisby isn’t just using his fake death to escape the world’s travails. He’s using it as perfect cover for the perfect crime. Once he’s ‘dead’, he will murder Bannister. There’s partnership insurance for $100 grand. And with both he and Bannister dead, the suddenly single Mrs. Bannister will join Grisby in the south seas, $100,000 the richer.

I don’t remember from the movie this part at all, frankly (it has been a while). But I do recall a confused sense of fuzziness at why Grisby wanted to fake his own death and murder Bannister.

In the book the murder plan makes perfect sense when it becomes clear that Grisby is in love with Elsa Bannister — he has every reason in the world to want to kill her husband and take his place. But in the film Grisby comes off quite pervy and queer and displays not the slightest interest in the breathtaking Rita Hayworth (Elsa Bannister). He seems more attracted to Orson Welles’s sailor. As a result the Grisby’s motive has always confused me til now.

Another note about Rita Hayworth, Elsa Bannister, and the adaptation. Rita Hayworth was famous for her flaming red hair. As was Elsa Bannister. Yet in the film Welles made Hayworth dye her hair blonde. Another odd dissonance. And she’s never been to Shanghai!

In any case, in both film and book it is Grisby’s body found slain, our innocent sailor bound to blame.

I won’t get into the ending — but while the result is the same, the manner of getting there is completely different. There’s no thrilling escape from custody, there’s no scene in the abandoned funhouse, no shooting shattered funhouse mirrors, shards splayed in bodies lain.

And so frankly, after the thrilling film, the book’s ending is relatively quiet and staid. Again — it’s the same result. But the joy is in the ride and the ride is not nearly so wild and dipsy doodle and crashing as the film.

So read it if you want. It’s good but not great. And not nearly so great as the film. Which, sadly, is diminished rather than enhanced with the reading of the book. It’s a book whose esteem would be greater had it never been adapted by a greater genius than the author of the book.