FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

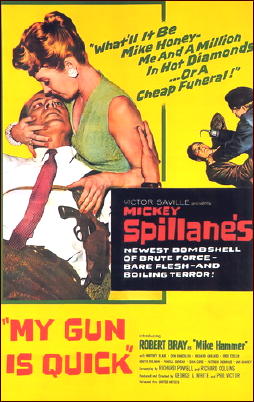

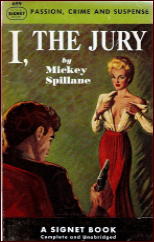

Anyone who’s read Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer novels — by which I mean the early ones, dating from 1947 to 1952, the ones in which Spillane overturned the whole Hammett-Chandler PI tradition by portraying Hammer as a sadistic psycho — has his own idea who should have played the character on screen.

There’s a consensus that the actors cast in the part were inadequate except perhaps for Ralph Meeker in director Robert Aldrich’s subversive version of KISS ME, DEADLY (1955), where Hammer is not the Cold War jihadi Spillane imagined but a cheap punk. It may not be coincidence that Meeker bore a certain physical resemblance to Spillane.

For my money the ideal screen Hammer would need to be a big bruiser, and of the actors from the period who are familiar to me the one I see as most like the character Spillane created was Lawrence Tierney (1919-2002). I challenge anyone to watch Tierney in that fine film noir BORN TO KILL (1947) and tell me he isn’t Hammer to the life. And judging from what I read on the Web, he was also a raging bull in the real world, serving several jail terms for beating people up in bars.

The years of the early Spillane novels coincided with the dawn years of television, but the medium’s antipathy to sex and strong violence seemed to rule out Hammer as a star of the small screen. Then in the late 1950s the character invaded America’s living rooms in the person of Darren McGavin (1922-2006), who went on to star in several other series including RIVERBOAT, THE OUTSIDER and KOLCHAK, THE NIGHT STALKER.

According to an interview McGavin gave decades later (Scarlet Street, Fall 1994), “Universal had made a contract with Spillane, and they made three pilots, one with Brian Keith. They couldn’t show them because they were all too violent.â€

The Keith pilot was written and directed by soon-to-be-superstar Blake Edwards (1922-2010). I’m told on the Web that it’s out there, and someday I’d love to see it. Keith as he looked in the Fifties strikes me as an excellent choice for the part, certainly more so than McGavin, who like Ralph Meeker resembled Spillane more than the Mick’s most famous character.

“I was doing a play in New York,†McGavin recalled, “and they called me to come out and do this series. I read the script…[and] said, ‘This is ridiculous! I mean, you can’t take this shit seriously….[T]his is satire. It’s gotta be satirical.’ [The producers] said, ‘No, no, no—this is really very deadly, straight-on, dead-on serious.’â€

McGavin insisted on playing the part his way, and Universal bigwig Lou Wasserman came down to the set and told him, “You can’t make fun of this material.†McGavin said, “I’m not making fun of it, I’m just treating it in a lighter manner…. We have a contract for me to say the words that are put on the paper. I don’t want anybody telling me how to do it.†What the hell did he think a director was for? Amazingly, McGavin wasn’t fired, and according to him, the episodes “were instantly successful. People thought they were funny.â€

Spillane couldn’t have cared less how the character was portrayed, telling TV Guide “I just took the money and went home.†That magazine’s reviewer declared that HAMMER “could easily be the worst show on TV.†I have yet to find anyone who considered the program a laugh riot but it certainly was successful, running for two seasons of 39 episodes each. All 78 can be accessed on YouTube and are also available on a DVD set.

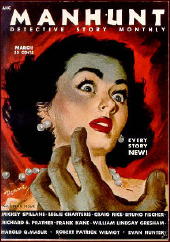

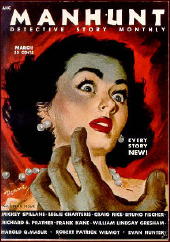

If the series wasn’t like the Hammer novels and wasn’t a comic parody of Spillane either, how can we describe it? I suggest we think of it as a sort of visual counterpart of Manhunt, the digest-sized crime magazine that debuted in 1953, at the height of Spillane’s popularity, and printed tons of tales by those hardboiled writers who were clients of the Scott Meredith literary agency. I don’t think it was by chance that later in the decade several of those writers got to crank out Hammer scripts, or have their Manhunt stories adapted for the Hammer series, or both.

To take the latter situation first, let’s look at Evan Hunter (1926-2005). By the time Hammer made it to the small screen, Hunter was writing mainstream bestsellers under his official name and the 87th Precinct police procedurals as Ed McBain. Earlier in his career he’d been writing tons of short stories for the hardboiled mags.

It was in Manhunt that readers of the Red Menace era first encountered an edgy alcoholic PI named Matt Cordell. Although originally published as by Evan Hunter, the byline and the protagonist magically changed their names to Curt Cannon when the stories were collected as the paperback original I LIKE ‘EM TOUGH (Gold Medal pb #743, 1958), soon to be accompanied by the novel I’M CANNON—FOR HIRE (Gold Medal pb #814, 1958).

Hunter’s career had skyrocketed so far into the stratosphere that he wasn’t interested in writing for the Hammer TV series, but three of his six Cordell stories from Manhunt were adapted by others into Hammer scripts. Hunter, needless to add, was a Scott Meredith client. So was Henry Kane (1908-1988), who found one of his Manhunt tales about PI Peter Chambers reconfigured as a Hammer exploit.

So was Robert Turner (1915-1980), who devoted a chapter of his memoir SOME OF MY BEST FRIENDS ARE WRITERS BUT I WOULDN’T WANT MY DAUGHTER TO MARRY ONE! (Sherbourne Press, 1970) to his experiences working on the Hammer series. As Turner tells it, a whole pile of Scott Meredith clients got flown out to La-La Land and tried their hands at writing for the program but only a few succeeded.

First and by far the most successful was Frank Kane (1912-1968), who was credited with 14 original scripts, 5 more written with a co-author, and 6 Manhunt tales (three of them about his own PI Johnny Liddell) Hammerized either by himself or somebody else. Kane had a habit of using gallows-humor titles for his novels and stories, and both he himself and others tended to use the same type of title for their HAMMER episodes.

Witness the following lists:

KANE NOVEL OR STORY

Bare Trap

Gory Hallelujah!

Lead Ache

Morgue-Star Final

Poisons Unknown

Slay Ride

Slay Upon Delivery

Trigger Mortis

HAMMER SCRIPT BY KANE

Crepe for Suzette

A Detective Tail

A Grave Undertaking

Lead Ache (based on Kane’s short story)

Skinned Deep

Slay Upon Delivery (not based on Kane’s short story)

HAMMER SCRIPT BY SOMEBODY ELSE

Bride and Doom

The High Cost of Dying

Just Around the Coroner

Merchant of Menace

My Fair Deadly

Stocks and Blondes

Swing Low, Sweet Harriet

Robert Turner described Kane as “a big, bluff, hearty guy with a sometimes bawdy but always lively sense of humor… He drove [the producers] crazy, because he steadfastly refused to make carbon copies of his scripts.†He “could turn out a first draft in one or two days. He never gave it to [the producers] right away, though. Not after the first time, when they told him it couldn’t possibly be any good if he’d written it that fast. From then on he just threw the thing in a drawer for two or three days and visited around the lot.â€

He “would come to Hollywood for a month, write four or five scripts, and as soon as the last one was finished and okayed wouldn’t even wait for his check, but would head back to his family in New York….He always took the train….â€

Another well-known crime novelist turning out Hammer exploits was Bill S. Ballinger (1912-1980), who under his B. X. Sanborn byline wrote about a dozen scripts for the series. Most of what didn’t come from East Coast hardboilers was the work of four men who over the years turned out a small army of scripts for Revue Productions’ syndicated TV programs: Fenton Earnshaw, Lawrence Kimble, Barry Shipman and, most prolific of all, Steven Thornley (reportedly a byline of prime-time teleplaywright Ken Pettus).

How about the guys who called the shots? The busiest of the Revue contract directors who worked on HAMMER was Ukraine-born Boris Sagal (1923-1981), who signed 20 of the initial 39 episodes plus 5 from the second season. Sagal soon became one of the top TV directors but his career came to a messy end: while filming the mini-series WORLD WAR III, he walked into the tail rotor blades of a helicopter and was partially decapitated.

Also noteworthy among the first season’s directors was John English (1903-1969), one of the great action specialists who spent much of his creative life helming B Westerns and cliffhanger serials at the legendary Republic Pictures. English moved into television when the new medium displaced theatrical B features and spent several years at Revue.

He directed only five segments of HAMMER but “Peace Bond†boasts perhaps the most exciting climax of any of the 78 episodes. McGavin’s mano a mano with an evil lawyer (Edmon Ryan) represents Republic-style action at its no-prop-left-unsmashed finest, every moment perfectly choreographed and complemented by the background music of Republic veteran Raoul Kraushaar.

English’s best bud at Republic was my own best friend in Hollywood, William Witney (1915-2002), the Spielberg of his generation, a wunderkind who at the start of his career was the youngest director in the business. Between 1937 and 1941 the two co-directed 17 consecutive Republic serials, their visual styles so much alike that they often got into arguments about who had shot what.

In the late Fifties, after Republic folded, Witney wound up at Revue, directing episodes of many of the same series English was working on, including MIKE HAMMER. During its second season Bill helmed 13 segments, far more than anyone else except Boris Sagal.

His HAMMER work benefits from innovations like devising L-shaped sets, with the camera positioned at the right angle of the L so he could have it point east and shoot one scene while the technicians were preparing the north arm of the L for the next sequence, then have it swing around, point north and shoot that scene while the crewmen were tearing down the furnishings from Bill’s first shot and setting up what was needed for his third.

If you watch only one of his 13 HAMMER segments, make it “Wedding Mourning†— the last episode filmed, he told me — in which Hammer for once is portrayed as something very close to the brutal psycho Spillane all unwittingly had created. Mike falls for a woman and is about to get married and change his life when his love is murdered and he runs amok, shooting and beating a swath through New York’s lowlifes. If any of the 78 HAMMER episodes qualifies as telefilm noir, this is it.

In the cast lists of any Fifties series you’re likely to find a number of men and women who were prominent in movies from earlier decades and others who were to become famous on TV in the Sixties or later. Among those once better known who appeared in HAMMER episodes were Neil Hamilton, Allan “Rocky†Lane, Keye Luke, Alan Mowbray, Tom Neal and Anna May Wong. The first three also enjoyed later TV fame, respectively as BATMAN’s Commissioner Gordon, the voice of the titular horse on MR. ED, and KUNG FU’S Master Po.

The actors who weren’t all that well known at the time of their HAMMER roles but made their marks later include Herschel Bernardi, Barrie Chase, Michael Connors, Angie Dickinson, Robert Fuller, Lorne Greene, DeForest Kelley, Dorothy Provine and Robert Vaughn. Anyone who can identify all these folks’ claims to fame either is a telefreak of the first water or has the DVD set.

While cobbling this column together I was presented with a copy of the set and have begun watching the episodes. Some of them I haven’t seen in many years, others — mainly those directed by Bill Witney or Jack English — I taped when the series was broadcast on the Encore Mystery Channel.

Will I make it through all 78? Dunno. Will I find anything interesting enough for another column? No idea. But if McGavin’s later PI series THE OUTSIDER ever comes out on DVD it might be worth exploring.