Mon 17 Mar 2014

by Francis M. Nevins

Health issues, tax chores, snow — I have more excuses for the lateness of my latest column than a toad has warts. This month we cross the Atlantic and resurrect my impressions of some British whodunits I read back in the late Sixties and Seventies. I didn’t read them in chronological order but I’ll arrange them that way for the column.

Leslie Charteris’s Meet—the Tiger! (Ward Lock 1928, Doubleday Crime Club 1929) is just as cornily melodramatic as the title suggests, featuring a pure heroine whom the mustachioed leering villain tries to force into marriage and a hidden mastermind captaining a clutch of super-crooks.

What saves this book from the graveyard of worthless imitations of Edgar Wallace is that its hero, appearing for the first time, is a daring young swashbuckler christened Simon Templar but better known as The Saint.

Simon’s two-front war against Scotland Yard and the super-crooks for the prize of a fortune in gold hidden somewhere around a Devonshire village lacks the gleeful outrageousness in plotting, prose and people-drawing that was soon to become the hallmark of the Saint Saga, but its historic interest is hard to deny.

H.C. Bailey’s Garstons (Methuen, 1930; U.S. title The Garston Murder Case, Doubleday Crime Club 1930) is set on the palatial estate of the munitions-manufacturing Garston family and in the surrounding towns and villages.

The 20-year-old disappearance of an obscure chemist whose formulas the Garstons may have stolen, the theft of some cheap jewelry from the fiancée of a long-dead Garston scion, and the strangulation of the ailing matriarch in a dark archway of the family castle, blend into a neat problem for psalm-spouting criminal lawyer Joshua Clunk.

Bailey here uses the multi-viewpoint approach, putting us inside the heads of Clunk, his Scotland Yard antagonist Superintendent Bell (who will be familiar to readers of the author’s Reggie Fortune stories), a local inspector, a Jane Eyre-like nurse, and the young student who falls for her in the chaste old-fashioned way.

The interplay of each one’s knowledge with the others’, some fine scenes of interrogation and recapitulation, and a wealth of details of time and place and history and geography combine to make this long, slow, carefully constructed work a model British detective novel of the Golden Age.

George Bellairs’ Death of a Busybody (John Gifford 1942, Macmillan 1943) finds genial Inspector Littlejohn paying a wartime visit to the town of Hilary Magna to find out who drowned the village voyeur in the vicar’s cesspool.

He encounters some amusing bucolic suspects and his investigation moves more briskly than is customary in English whodunits, but the climax is clumsily structured, the solution is reached purely by legwork, and the culprit is obvious to readers (though not to the supposedly seasoned officials) as soon as he offers his alibi.

A sharp incidental picture of a country hamlet in wartime is the highlight of this all too average specimen.

In Harry Carmichael’s Put Out That Star (Collins, 1957; U.S. title Into Thin Air, Doubleday Crime Club 1958) we follow insurance investigator John Piper as he looks into the disappearance of a glamorous British movie queen from a fashionable London hotel.

Eventually he discovers how, who and why, but the only readers who won’t have tumbled to the truth a hundred pages ahead of Piper are those who are completely innocent of the hoariest cliche denouement in English mystery fiction.

Carmichael also manages to slip in the most hackneyed American climax in the genre and to leave several huge holes in the plot. Quite an achievement, yes?

A Murder of Quality (Gollancz 1962, Walker 1962) casts John LeCarre’s ex-spy George Smiley in the unusual role of private sleuth, invading Dorsetshire’s posh and snobby Carne School in order to look into the fatal bludgeoning of an instructor’s wife shortly after she stated that she was afraid her husband was trying to kill her.

Smiley pokes into the animosities between townies and gownies and between the Anglicans and the Baptists without neglecting physical clues like the piece of bloody coaxial cable and the altered examination paper, but LeCarre never clarifies how Smiley reached his solution nor what the murderer’s plan was.

However, the confused plot is balanced by fine evocations of scene and character, including two of the bitchiest females I’ve ever encountered in a whodunit.

John Creasey’s The Depths (Hodder & Stoughton 1963, Walker 1967) isn’t really a mystery but a blend of philosophy, SF and suspense that’s typical of his postwar novels about Dr. Palfrey and the international organization Z5.

This account of Palfrey’s war against the mad-scientist ruler of an undersea kingdom who’s discovered the secret of prolonging life indefinitely and can also create tidal waves powerful enough to destroy any ship or seacoast in the world crawls at snail speed and bulges with plot holes.

But it’s worth reading for a few fine character sketches — notably that of another doctor who slowly discovers a humanistic conscience — and especially for the climax where Creasey evokes the moral nightmare of politico-military decision-making in today’s world. The implied value judgments may rouse readers to fury but very few of the tough questions are evaded in this early specimen of the techno-thriller.

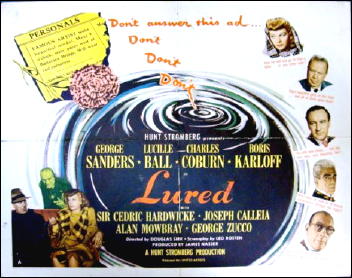

Douglas Clark’s Deadly Pattern (Cassell 1970, Stein & Day 1970) is a plodding and drearily written quasi-procedural in which snobbish Detective Chief Inspector George Masters and his three Scotland Yard subordinates are dispatched to a tiny coastal town to investigate the almost simultaneous disappearances of five drab middle-class women.

When four of them are found buried by the seashore, Masters and company crawl into action, taking 169 pages to uncover a psychotic killer whose identity should be apparent to every reader by page 30.