Sat 28 May 2011

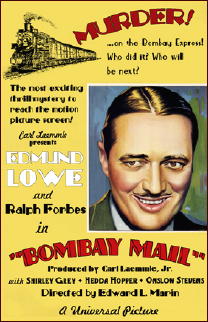

BOMBAY MAIL. Universal Pictures, 1934. Edmund Lowe (Inspector Dyke), Ralph Forbes, Shirley Grey, Hedda Hopper, Onslow Stevens. Based on the novel by Lawrence G. Blochman. Director: Edwin L. Marin.

In the novel, the leading detective is Inspector Leonidas Prike, who made repeat appearances in two later Blochman novels, Bengal Fire (1937) and Red Snow at Darjeeling (1938). All three books, rather obviously, take place in India.

But Bombay Mail also has the advantage, as far as I’m concerned, of taking place on a train, which in case of the motion picture is a huge plus, with the clickety-clack of the wheels on the track being heard at least 98% of the time. (I say this even though it was filmed, I’m sure, on a stage set).

What Inspector Dyke must learn, as the trains cuts across the Indian sub-continent from Calcutta to Bombay, is first who poisoned the British governor of Bengal (lots of suspects on the train, with lots of reasons – one per suspect, at least), then who shoots the Maharajah of Zungore before he can tell Dyke what he knows and who he saw doing what.

There is, as there has to be, one femme fatale among the suspects, and in Bombay Mail she is played by Shirley Grey, known in some circles as Russian opera singer Sonia Smeganoff, and by others as plain Beatrice Jones (on her passport).

Questions: Who supplied her with the ticket she needed to be on the train before she was deported? Who had access to the cyanide used? (Quite a few, as the Inspector Dyke soon learns.) Who is the mysterious Mr. Xavier, and who is the dangerous-looking man he hires to keep an eye on John Hawley? Why does the scientist Dr. Lenoir carry a deadly king cobra snake around in his handbag? And what are those valuable rubies doing in Hawley’s tobacco pouch?

This is definitely my kind of movie, and maybe yours as well, but overall I was disappointed. There is too much plot for too little playing time (70 minutes or so), and it takes a long time for the viewer (me) to sort out who all the players are and what the connections are between them. Perhaps I was slow on the uptake, but I believe another 20 or 30 minutes of movie time would have been useful.

I’m still going to recommend this movie to you. One should never complain too loudly about too much plot in a detective movie, especially one that takes place on a train. When I watch this one again, and I will, I’m going to enjoy it immensely.