Mon 25 Oct 2021

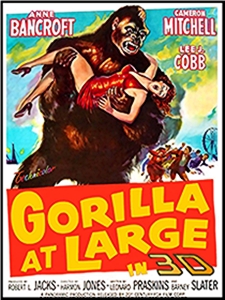

A Movie Review by David Vineyard: MAN AT LARGE (1941).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[3] Comments

MAN AT LARGE. 20th Century Fox, 941. Marjorie Weaver, George Reeves, Richard Derr, Steve Geray, Milton Parsons, Elisha Cook Jr., Richard Lane, George Cleveland, Kurt Katch. Screenplay: John Larkin. Directed by Eugene Forde.

Who are the Twelve Whistling Men?

That’s the question in this spy comedy released just before America’s entrance into the Second World War as wanna be newspaper photographer Dallas Dayle (Marjorie Weaver) gets her shot at a real job on a New York newspaper when she’s assigned by editor Richard Lane to cover the story of a German Ace who escaped from a Canadian internment camp and is expected to cross over into the United States on his way to Canada.

Complicating things is rival reporter Bob Grayson (George Reeves) who she thinks murdered German fifth columnist Hans Brinker (Kurt Katch) in the newspaper reception room. We know he was killed by a sinister man with a silenced gun (Milton Parsons), but when Grayson shows up at the same motel on the border as Dallas and the killer, then meets with the escaped German flyer (Richard Derr), it starts to look more than a little suspicious, especially when another German agent at the motel (Spenser Charters) who meets with the killer is murdered like Brinker. Grayson and Dallas are arrested for it by Sheriff George Cleveland while Grayson tries to steal the camera Dallas snapped a photo of the German flyer with.

Just what are the Twelve Whistling Men the dying Brinker whispered about, and what do they have to do with the passage from “Peter and the Wolf” everyone seems to be whistling, and a pulp story that is uncannily close to exactly how the German flyer escaped in the first place and seems to be popping up everywhere? And what does that have to do with convoys carrying supplies to England being sunk?

Following the style, and a bit more (Grayson and Dallas get handcuffed together at one point) of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Thirty-Nine Steps, Man at Large doesn’t move, it positively gallops hardly giving the viewer a chance to breathe from the opening escape in the dark to the final clench.

Little surprise that. Screenwriter John Larkin was one of the brightest lights of the B film of the period, penning and directing Quiet Please, Murder! an early film noir about a stolen Shakespeare Folio, murder, Nazi art collectors, and a masochistic thief. With the capable Eugene Forde directing this little gem fires brightly from Weaver’s screwball Dallas, Reeves fast talking mystery man, and a fine assortment of German agents.

Back in New York Dallas tracks down the pulp author who proves to be wealthy Karl Botany (Steve Geray), a suave blind man whose recently hired secretary is none other than one Mr. Sartoris (Milton Parsons).

Up to this point things haven’t been moving slowly, but now the kick into overdrive with Grayson and the German flyer tying Dallas up as they go to meet a contact, Dallas escaping with help from hotel clerk Elisha Cook Jr., the real Nazis revealed, much more confusion on Dallas part, more dead bodies, Grayson and Dallas doing a mind reading act in a run down girly show theater, and no one, including the viewer, quite sure who anyone is until the final confrontation.

The plot, almost more than this B film can bear, manages to hold up well enough to keep you entertained without asking too many questions, and most of the ones you might ask are covered by the various reveals without bothering to explain them to the viewer.

No one takes a long enough breather for that. Anything not covered by the breathless plot really doesn’t seem worth worrying about anyway.

I’ve been looking for this one for years and only recently found it. Happily it is no disappointment. It’s fast, fun, attractively acted, and the polish of the B department of Fox in the period shows despite its lowly origins.

This might have fared well as an A with a better known cast, it’s that good.

The print I saw is flawed, and I really have no idea if a better one exists, but this is a small delight. Just buckle in and enjoy.