The Tale of Mr. Fergus Hume and Mr. William Freeman

or, The Reviewer’s Comeuppance

by Curt J. Evans

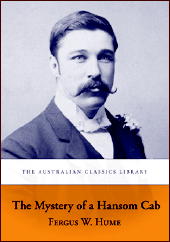

Despite having produced over 130 mystery novels between 1886 and 1932, the year of his death, the English born, New Zealand raised author Fergus Hume (1859-1932) is known — to the extent he is known at all today — for one work, his debut murder tale, The Mystery of a Hansom Cab.

Accounts typically claim that over 500,000 copies of Hansom Cab were quickly placed into eager purchasers’ hands (some sources suggest up to as many as a million copies may have been sold), making the novel a landmark financial success within the mystery genre.

After relocating from New Zealand to Australia in the 1880s and finding employment as a barrister’s clerk, Fergus Hume soon manifested marked literary tendencies. He published a few stories and began writing plays, but the latter efforts went nowhere. Determining that what the public really desired was a murder tale, Hume pored over the celebrated mystery novels of the French author Emile Gaboriau (1832-1873). Then he produced his own crime story, The Mystery of a Hansom Cab.

Finding resistance among Australian publishers to this work as well, Hume was forced to the expedient of privately printing it. To everyone’s amazement the novel sold briskly. Hume then made the mistake of his life, for a pittance parting with the book’s copyright to an Australian publisher who soon had it flying off shelves not only in Australia but Great Britain and the United States. Apparently Hume never made a penny off the book again.

Undaunted by his ill turn of economic fortune, Hume determined to make his living as a novelist. By 1888 he had moved to England (where he would live the rest of his life) and had ditched his Australian publisher. The next year saw the publication of Hume’s first mystery novel set in England, The Piccadilly Puzzle.

A fascinating review of The Piccadilly Puzzle appeared in the inaugural issue of Zealandia, a short-lived New Zealand literary journal (it ran for twelve issues). The reviewer of Puzzle, William Freeman, was also the editor of Zealandia and a prominent New Zealand journalist of his day. His review of the tale is acute but also strikingly harsh in tone. However, if Hume was offended by this review, he soon enough had the last laugh on Freeman.

Before I get to the Zealandia review and the bizarre fate of the reviewer, however, some words about The Piccadilly Puzzle are necessary.

Clearly inspired by the recent Jack the Ripper murders (as was another Victorian mystery novel published at this time, Benjamin Farjeon’s Devlin the Barber), The Piccadilly Puzzle revolves around the mysterious murder of a woman on a foggy night in a major London thoroughfare.

The woman, initially thought to be a “streetwalker” (shades of the Whitechapel murders) soon is identified as a certain Miss Sarschine, the mistress of a prominent lord who, it seems, has just eloped to the Azores on his private yacht with another lord’s wife. The dead woman was not strangled or stabbed but, rather, poisoned — the poison apparently being one of those convenient tropical toxins utterly unknown to Western science, the use of which later would be much frowned upon in the Golden Age of the detective novel (roughly 1920 to 1939).

Perhaps not coincidentally, poor defunct Miss Sarschine, that lovely lady of easy virtue, had a pair of Malay kris, complete with fatally poisoned blades, hanging on a wall of her love nest (apparently deadly poisoned kris on the wall add just that right final touch to a romantic evening).

The London police put a private detective named Dowker entirely in charge of the case (something which struck me as rather odd). As a character this Mr. Dowker is not interesting at all, but, worse yet, he has a “colorful” Cockney sidekick, a street urchin named Flip, who speaks like this:

“ ’e gives me sumat to eat when I arsks it, so I goes h’up to cadge some wictuals, I gits cold meat, my h’eye, prime, an’ bread an’ beer, so when I ’ad copped the grub, I was a-gittin’ away h’out of the bar when a swell cove comes in — lor’ what a swell — fur coat an’ shiny ’at. Ses to the gal, ses ’e….”

As much as I admire Hume’s perseverance in typing so many apostrophe marks, I have to confess my eye flew past Flip’s speeches as fast as was possible. I have to wonder whether Hume was inspired to create Flip by Arthur Conan Doyle’s ragamuffin assistants to Sherlock Holmes, the Baker Street Irregulars, who had appeared in the premier Holmes tale, A Study in Scarlet (1887). I cannot recall the Irregulars speaking quite so irregularly as our friend Flip, but perhaps my memory is playing me false.

The mystery in The Piccadilly Puzzle is certainly as convoluted as Flip’s speech (in addition to untraceable poisons, Hume for good measure also throws twins — another Golden Age no-no — into the mix as an additional plot complication); but, alas, it is not really fair play, an overheard confession being necessary to accomplish the killer’s exposure.

Hume became known for having a consistent narrative construction in many of his mystery tales, whereby a series of individuals are suspected in turn, only to have Hume pull a “surprise” culprit out of his top hat.

This keeps the story rolling along, but makes the wary reader immediately look for the culprit among the characters whom no one suspects. It’s the least likely suspect gambit famously associated with Agatha Christie, but Hume lacks the Golden Age Crime Queen’s uncanny finesse.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about The Piccadilly Puzzle is the sexual immorality (or amorality) of the characters, which is portrayed with striking casualness by the author.

One would conclude from this tale that the English aristocracy in 1889 was hopelessly debauched. One lord seduces a young woman, sets her up in a London love nest, then commences an affair with a woman married to another lord (in an exceedingly odd twist, this woman turns out to be the identical twin sister of his aforementioned mistress).

Additionally, we learn that the straying wife had already had a sexual affair with another, younger man, before breaking with this man to marry the lord (she was ambitious for a title). After learning of his wife’s wayward ways the lord she married regrets that he impulsively wed the hussy rather than simply make her his mistress, as the other lord did with the other sister.

“Sounds like the second act of a French play,” remarks one character. Indeed!

It is perhaps worth noting that Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray was published a year after The Piccadilly Puzzle. Wilde’s famous short novel incurred some considerable criticism that year as “nauseous,” “unclean,” “effeminate” and “contaminating.”

While Fergus Hume clearly had not attempted a work of literary ambition in The Piccadilly Puzzle, he nevertheless in the tale gave readers a whiff (whether fragrant or foul depending on the individual) of fin de siecle decadence.

Which brings us, finally, to William Freeman’s hostile piece on The Piccadilly Puzzle in the pages of Zealandia. Rarely have I encountered such a scathingly detailed review of a mystery novel. In Freeman’s eyes, the work was a failure on all counts, literary, technical and moral.

At the time Freeman wrote his condemnatory review of Hume’s fifth mystery tale, Hume was a New Zealand national celebrity, author of, as Freeman put it, “the most successful novel of the day.”

To be sure, Hume soon would be overtaken and surpassed by Arthur Conan Doyle (who had already published A Study in Scarlet in 1887 and would produce, in an explosion of creative genius, The Sign of Four and the dozen short stories comprising The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes in 1890-1892).

Yet by producing mystery tales at an awesome rate — he was, along with the later Edgar Wallace and John Street, one of the most prolific producers in the history of the mystery genre — Hume managed to maintain a relatively successful writing career over the next quarter century or so.

Only after the outbreak of World War One, when he lost his American publisher, G. W. Dillingham, and the onset of the Golden Age, when his health declined and his books came to seem increasingly antiquated, did Hume find his financial prospects darkening. His last years were spent in a single rented room in a bungalow and he died in near poverty, only a couple years after his onetime rival Conan Doyle.

Yet those dark days were a long way off in 1889, when Hume was still big news and interest in his literary fate was high, especially in New Zealand, where he was the colonial who had astonished the writing world (even if he had not always impressed it: “What a swindle The Mystery of a Hansom Cab is,” wrote Arthur Conan Doyle bluntly in a letter at this time. “One of the weakest tales I have read, and simply sold by puffing.”).

Like Conan Doyle, William Freeman, a noted controversialist in his day, was not one to be intimidated by fame. Freeman himself had authored in 1889 a sensation tale (modeled on Charles Dickens) entitled, with unwitting prescience on his part, He Who Digged a Pit.

In the very opening lines of of his review of The Piccadilly Puzzle, Freeman made his poor opinion of Hume’s latest crime novel brutally plain. The book, he wrote damningly–

“…is not a tale: it is a bald bare plot, with nothing good and pleasing to recommend it. It has absolutely none of the touches of poetic descriptive, pathos and humor which explain the popularity of [Hume’s] earlier books. There is not a fine sentiment in it from cover to cover; no tender chords are stirred by a single passage; there is no delicate shading, no touch of an artists’ hand; nothing new–no anything but a sombre, highly sensational plot, and an unadorned description of an impossible detective’s unavailing efforts to unravel the tangled clues of a crime, the original of which is clearly one of the Whitechapel murders.”

In addition to finding The Piccadilly Puzzle poorly written — its prose lacked the “beauties which hid the repulsiveness of the plots in [two of Hume’s earlier tales, The Mystery of a Hansom Cab and Madame Midas]” — Freeman damned the book as well for essentially failing to adhere to what some thirty years later, in the Golden Age of the detective novel, would be called the fair play standard.

In Freeman’s eyes Fergus Hume did not play fair with his readers but, rather, with out-of-bounds mendacity led them down the garden path:

“The most remarkable feature about the characters is that very nearly all of them (the hero included) scatter about a reckless profusion of lies, introduced not at all because they are necessary but solely to mystify the reader. The author leads the way himself in this deception, for at the very outset he deliberately misleads the reader as to the thoughts of the murderer (pp. 5 and 7) and throws suspicion on the hero by making him start at hearing mentioned the name of the street in which the murder is committed (p. 6), though at the time he had no idea that any murder had been perpetrated and there was no reason he should attach more importance to a mention of Jermyn Street than any other street in the city. It is permissible in fiction to so relate actions as to infer [sic] that an innocent man is guilty, but surely both the above artifices are unjustifiable.”

Freeman also takes Hume to task at length for the numerous improbabilities the author scattered throughout his tale, ending by asserting, “to solely construct a whole plot out of nothing else [but improbabilities] is straining the credulity of readers too far.”

Having disposed of Fergus Hume’s writing and plotting to his own evident satisfaction, Freeman then proceeded to blast The Piccadilly Puzzle for sundry moral transgressions. This line of argument was to prove ironic in the face of Freeman’s own subsequent behavior.

“The worst feature of the book,” thundered Freeman righteously, “is its moral tone.” In Freeman’s horrified eyes, the characters of The Piccadilly Puzzle wallowed “in a seething mass of moral corruption which the author cynically disdains to hide behind the slightest shadow of the veil of decency.”

Indeed, Hume seemed “to consider it natural that everybody should be immoral.” He portrayed this immorality “with a coarse fidelity” that Freman found “positively repulsive.”

Freeman closed his resoundingly minatory review article by expressing his “emphatic condemnation” of other New Zealand writers embarking on such a “dangerous” literary course as Fergus Hume had. Hume now represented New Zealand before the eyes of the world, Freeman noted. Sadly, he had shirked his duty as an author to stand with that “which is clean, wholesome and pure-minded.”

I personally would love to know what Fergus Hume made of Freeman’s review of The Piccadilly Puzzle.

Or of the sudden and surprising downward turn in Freeman’s own personal fortunes:

Zealandia soon went defunct and in 1890 Freeman (whose full name was William Freeman Kitchen) had become the editor of the Dunedin Globe. A year later he resigned from the paper, amid great controversy. (The paper under his management made what were later determined by government investigation to be baseless charges against the Seacliff Lunatic Asylum, its offices were subjected to arson and Freeman was found to have lied about the amount of money the paper was losing each month.)

By 1893 Freeman had moved to Australia, where it was announced in a newspaper that he had died, leaving behind his wife and two children in New Zealand. Yet that same year Freeman was discovered in the flesh, very much alive and in the company of a female correspondent. He had, it seems, falsely announced his own death. He was arrested and tried for desertion and bigamy. Ultimately he committed suicide in 1897, at the age of 34.

Truly, a turn of events almost (if not quite) as odd as those in The Piccadilly Puzzle! As far as I know, however, no twins and no tropical poisons unknown to science were involved in the real life William Freeman Kitchen mystery.

Fergus Hume would go on for about another three decades to write an unbroken string of nearly one hundred more mystery tales–though his name tenuously survives in genre history only as the author of The Mystery of a Hansom Cab. While Hume’s The Picadilly Puzzle may be justly forgotten, William Freeman’s review of the novel deserves to be remembered.