PRIME TIME SUSPECTS (Crime & Mystery Television)

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

It is hardly surprising, perhaps, that one of the main reasons why so little has been written about the TV crime and mystery genre is that while everyone knows what constitutes as crime drama, no one has been able to define quite what it is. As has often noted before, the general consensus is that the crime and mystery, at its core, is a puzzle.

Essentially, when not a Whodunit (identifying the criminal) it is a Whydunit (the reasons for the crime). While the puzzle factor does indeed lie at the heart of the genre, the shape and structure of the puzzle may adopt a myriad of forms.

Certain basic characteristics can be deduced from the presentations themselves. It is more often than not contemporary. It has an urban setting (the city). It involves a crime of some nature (murder and robbery being among the foremost).

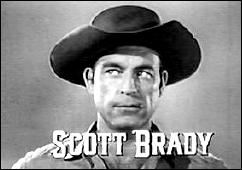

But these, of course, are not the mandatory hallmarks of a TV Crime & Mystery. The Western, for instance, has lawmen and outlaws, gunfighters and hold-ups, but they are hardly crime and mystery. Although in keeping with the TV vein here, the 1870s investigations of gunfighter/private eye for-hire Shotgun Slade (syndicated, 1959-61) and the police procedurals of Denver police detective Whispering Smith (NBC, 1961) may well be the cause for some constructive argument. And not forgetting Richard Boone’s early forensics in NBC’s Hec Ramsey (1972-74).

It has been expressed before that realism rather than stylization, a sense of authenticity and not outright adventure are the keynotes. The settings, the look, the narrative, and the procedure are all intended to be realistic. Or at least plausible. Content may often appear to be ritualized and behaviour somewhat stereotyped, but the characters are (in the majority of cases, at least) individuals rather than archetypes.

In this view, the TV genre is at times variably flexible and tends to be audience-led. It often bows to contemporary flavours and fashions. Its richest moments, however, offer access to a world not normally afforded the ordinary citizen, the slightly sinister world of the dogged detective or the cynical street cop, the nocturnal prowling of the private eye or the ice-cold operation of a secret agent.

The spirit of the genre is that law and order must be maintained at all costs, or, from the flip side of the coin, outwitted, outsmarted, and even defeated.

It can take the form of the pursuit: quiet and observational (as in Maigret [BBC, 1960-63], Agatha Christie’s Poirot [ITV, 1989-93; 1995]) or physically fast and furious (The Sweeney [ITV, 1975-76; 1978], Starsky and Hutch [ABC, 1975-79]), or even the long-form (The Fugitive [ABC, 1963-67]). It can be a psychological chess game (Cracker [ITV, 1993-96]), a medical examination (Quincy ME [NBC, 1976-83]), or a forensic probe (CSI: Crime Scene Investigation [CBS, 2000-present]).

The setting can range from Miss Marple’s cozy English village of St. Mary Mead to the dangerous night-time streets of The Wire’s Baltimore. Then there’s the milieu, the occupational routine of the sleuth. Or the social and/or professional world they inhabit. The hospital/medical milieu (Diagnosis Murder [CBS, 1993-2001]). The clerical milieu (Father Dowling Mysteries [NBC, 1989; ABC, 1990-91]). Wealthy eccentrics (Burke’s Law [ABC, 1963-65]). Horse racing (The Racing Game [ITV, 1979-80]). Et cetera, et cetera…

Because it contains so many elements and facets related to crime, engaging the viewer from a variety of directions, the TV genre can not be defined precisely.

The basic story-telling characteristics are an extrapolation of the forms and formats of, in one-part, the literary genre, one-part the radio drama and one-part the cinema. The TV form (not unlike the literary form) can embrace almost any genre, and can pursue any narrative strand. It can be set in the past or in the present. It can select as its point of narrative focus the law enforcer, the criminal, or the innocent bystander. It can be a TV play, a TV film, a miniseries/limited serial, an episodic series, or a series of self-contained episodes or thematic episodes (the anthology).

The detective or sleuth character is usually the leading figure in the narrative. Leading the path that the viewer is obliged to take, they follow the pattern of the investigation. It is the sleuth’s particular application to the details of the crime that provides the dramatic interest or action (whether the gung-ho tactics of a Lt. Frank Ballinger of M Squad [NBC, 1957-60] or the careful scrutiny of a Hercule Poirot).

The sleuth may have an assistant (Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson) or a partner (Inspector Morse and Sergeant Lewis). Or may consist of the a team (Ironside [NBC, 1967-75]) or a specialised squad (the cold cases unit of Waking the Dead [BBC, 2000-present]).

The subgenre of the private detective provides, usually, the loner (Peter Gunn [NBC, 1958-60; ABC, 1960-61], Shoestring [BBC, 1979-80]). Among the subdivisions are the amateur sleuths (Hettie Bainbridge Investigates [BBC, 1996-98], Kate Loves a Mystery [NBC, 1979]) and the sleuth couple (The Thin Man [NBC, 1957-59], Hart to Hart [ABC, 1979-84], Wilde Alliance [ITV, 1978]).

They can belong to established organisations (The FBI, Scotland Yard, MI5, the CIA, the French Sûreté, Interpol) or carry out their assignments on behalf of made-up agencies (U.N.C.L.E., C.O.N.T.R.O.L., Nemesis, CI5).

The most popular, and the most associated with the TV genre, has been the police drama. Mainly the Police Detective (Columbo [NBC, 1971-77; ABC, 1989-93], Inspector Morse [ITV, 1987-2000]) but also the Police Officer (Dixon of Dock Green [BBC, 1955-76], Joe Forrester [NBC, 1975-76]).

Among the subdivisions here are the undercover cop (Wiseguy [CBS, 1987-90], Murphy’s Law [BBC, 2001-2007]), the internal affairs/investigations cop (Between the Lines [BBC, 1992-94]), as well as the mobile cop (Z Cars [BBC, 1962-78], Highway Patrol [syndicated, 1955-59], CHiPs [NBC, 1977-83]).

The Adventurer. Thrill seeker; often on the lookout for dangerous and exciting experiences. Perhaps a round-up of the expected suspects along these lines would include Roger Moore’s The Saint (ITV, 1962-69), Robert Beatty’s Bulldog Drummond (in “The Ludlow Affair” pilot [ITV, 1958] for Douglas Fairbanks Jr Presents), The Agatha Christie Hour (with “The Case of the Discontented Soldier” [ITV, 1982]), Raffles (ITV, 1977), Josephine Tey’s Brat Farrar (BBC/A&E, 1986), Modesty Blaise (pilot; ABC, 1982), The Lone Wolf (syndicated, 1954), Jason King (ITV, 1971-72), The Baron (ITV, 1966-67) and, since this type of programming seems to have the greatest appeal to casual TV viewers, the countless others that we could all name.

The Private Detective (or Private Eye) has had a long and popular run in the TV genre. In the traditional American sense (77 Sunset Strip [ABC, 1958-64] as team, The Rockford Files [NBC, 1974-80] as loner) as well as the more British tradition of the ‘consulting detective’ (The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes [ITV, 1984-85], Agatha Christie’s Partners in Crime [ITV, 1983-84]), along with the occasional UK leanings toward the American style (Public Eye [ITV, 1965-75]).

The Hard-Boiled sleuth (Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer [syndicated, 1957-59]) comes into this category. Also the amateur sleuthings of The Snoop Sisters (NBC, 1973-74) and The Beiderbecke Affair (ITV, 1985), either by design (a sense of over-curiosity) or by accident.

Perhaps as a footnote to the private detective division is the insurance investigator (John Ireland in The Cheaters [ITV, 1962-63]) or investigator for the diamond industry (Broderick Crawford in King of Diamonds [syndicated, 1961]).

The Lawyer sleuth and the Legal Procedural offer stories combining both private investigation and courtroom drama (Perry Mason [CBS, 1957-66], Sam Benedict [NBC, 1962-63]), and in more recent times the format has been used for corporate as well as constitutional enquiry (L.A. Law [NBC, 1986-94], Judge John Deed [BBC, 2001-2007]).

Spies, government agents and espionage have been in the literary genre almost as long as the crime and mystery genre itself. However, for the most part, their activities on both the printed page and the small screen have been popular for as long as there has been established political enemies to fight – which means, the genre was popular for most of the last century and remains (with the threat of terrorism), unfortunately, popular today.

The television espionage genre has presented the spy (the Anglo-U.S. side, of course) as either a lone crusader (during the communist witch-hunt early 1950s; I Led Three Lives [syndicated, 1953-56]) or as part of a secret, highly organised corporation, an element that reached its peak of popularity (quite often as parody) during the 1960s (The Avengers [ITV, 1961-69], The Man from U.N.C.L.E. [NBC, 1964-68]).

Later, Callan (ITV, 1967; 1969-72) returned the genre to a more serious track, culminating in John le Carré’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy in 1979. The highly popular Spooks (BBC, 2002-present; in U.S. as MI-5), for instance, features a youthful team of operatives involved in anti-terrorist activities. And so it goes…

The Period Sleuth has been popular on UK television since the early 1970s. A winning combination of costume drama and detective fiction, the works of such authors as Christie, Conan Doyle, Dorothy L. Sayers, G.K. Chesterton, and others, have produced the sagas of Lord Peter Wimsey (BBC, 1972-75), Father Brown (ITV, 1974), Campion (BBC, 1989), the ITV Sherlock Homes series (with Jeremy Brett; 1984 to 1994), Agatha Christie’s Poirot (ITV, 1989-93; 1995) and The Mrs Bradley Mysteries (BBC, 1998-99). The fascinating Canadian series Murdoch Mysteries (Citytv, 2008-present) continues to fascinate.

Occasionally, there are observations on contemporary life from the distant viewpoint of ancient Rome and Medieval England (the Falco and Brother Cadfael stories, respectively). The most popular period, it seems, is the fairly recent past, roughly the late Victorian era of Sherlock Holmes and Jack the Ripper to the ‘nostalgic’ decade of the 1960s with Crime Story (NBC, 1986-88) and Heartbeat (ITV, 1992-2010).

A small note on the future and/or fantasy as ‘setting’: Isaac Asimov’s Caves of Steel (BBC, 1964); The Outer Limits (ABC) episodes “The Invisibles” and “Controlled Experiment” (both from 1964); The X Files (Fox, 1993-2002); Star Cops (BBC, 1987).

The Scientific Sleuth has surfaced intermittently over the decades (The Hidden Truth [ITV, 1964], The Expert [BBC, 1968-69; 1971; 1976]) until 2000 when CSI blazed a trail that brought the work of forensics experts to the fore.

Weapons and ballistics experts have featured in past stories, and currently Dexter (Showtime, 2006-present) has amassed an unexpectedly popular following by portraying the work of a blood splatter specialist (alongside his alter ego as a serial killer). The criminal psychologist has also gained a following over the years, especially with the success of Cracker in 1993 (Profiler [NBC, 1996-2000], Wire in the Blood [ITV, 2002-2008]).

Needless to say, there is more to the TV Crime & Mystery than just the above basic descriptions. In time, I intend to discuss aspects of the TV Gaslight Era drama, the Underworld, the Psychological Thriller, and other related TV forms.

In Part Two of PRIME TIME SUSPECTS, I will trace early examples of the genre (from 1930s/1940s TV works by Christie, Edgar Wallace, G.K. Chesterton, Patrick Hamilton and Edgar Allan Poe, among others), leading up to the episodic series of the late 1940s (such as The Plainclothesman, 1949-54).

Note: The introduction to this series of columns on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here.