Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

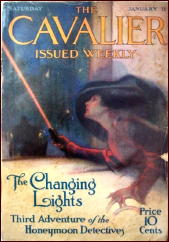

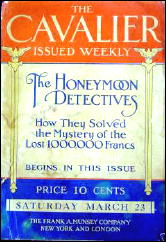

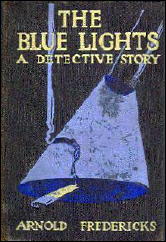

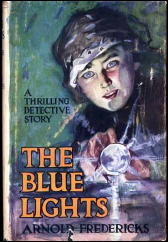

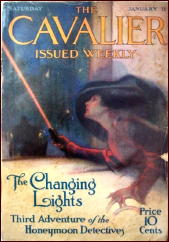

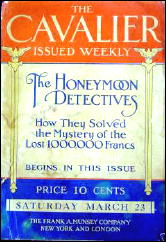

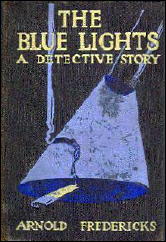

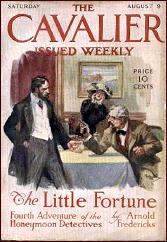

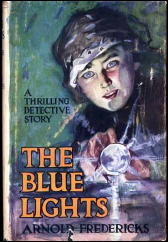

ARNOLD FREDERICKS – The Blue Lights. W. J. Watt & Co., hardcover, 1915. Hardcover reprint: Grosset & Dunlap, no date. Serialized (four parts) in The Cavalier as “The Changing Lights,” January 11 through February 1, 1913.

Before there was Nick and Nora Charles, or Pam and Jerry North, or even Lord Peter and Harriet Vane, a pair of happily married American sleuths were pursuing mystery across the international scene fighting crime tooth and nail.

Robert and Grace Duvall were the creation of Frederick Arnold Kummer, a popular mystery writer both under his own name, and as Arnold Fredericks and an early tie to the burgeoning new cinema as both a scenarist and like Arthur B. Reeve, the creator of Craig Kennedy, adapting films to print. He also co wrote musicals with Sigmund Romberg and Victor Herbert — not bad company.

The Duvalls debuted in the pulps in The Cavalier as “The Honeymoon Detectives,” a series Robert Sampson describes in Yesterday’s Faces, The Solvers (Volume 4) as “prose as bland as unsweetened farina.” There Robert Duvall, private investigator, and Grace Elliott, plucky American girl, met and fell in love. [Note: Follow the link above for a long excerpt from Bob Sampson’s book.]

Richard, as the series opens, is a “gifted” private detective assigned to the staff of M. Lefevere, Prefect of the Paris Police.

Despite being such a bright and gifted sleuth, Richard has nothing on Grace, who is front and center for most of their six adventures, finding more ways to get into trouble than Nancy Drew ever imagined. The six books cover a number of changes in the Duvall’s life. As The Blue Lights opens they are retired from crime fighting and living in Maryland on a plantation until Richard’s fame draws him reluctantly back into the world of crime and detection.

Their adventures are: One Million Francs ( in Cavalier as “The Honeymoon Detectives”), The Ivory Snuff Box (which opens exactly one hour after the first book ends), The Blue Lights (in Cavalier as “The Changing Lights), The Little Fortune, “The Mysterious Goddess,” and Film of Fear (in which Robert aids movie star Ruth Morton).

[Note: The publication dates for these adventures as they appeared in the pulp magazines can be found here. Unaccountably, “The Mysterious Goddess†has never appeared in book form.]

In The Blue Lights an American millionaire’s son has been kidnapped in Paris and his agent rushes to the Duvall’s Maryland estate to enlist Robert in the investigation:

“You must listen to what I have to say, Mr. Duvall, at any rate. Mr. Stapleton would not hear to my returning, after seeing you without having explained to you the nature of the case.”

Duvall leaned back, and began to fondle the long moist nose of the collie which sat beside his chair. “If you insist, Mr. Hodgman, I will listen, of course; but I assure you It will be quite useless.”

“I hope not. The case is most distressing. Mr. Stapleton’s only child has been kidnapped!”

“Kidnapped!” Duvall sat up with a start, every line of his face tense with professional interest. “When? Where?”

“In Paris. The cablegram arrived this morning…”

Stapleton is a banker who Duvall has worked for before — a “wealthy banker” as we are told (as opposed to a poor banker one supposes). Duvall reluctantly agrees to take the case. Robert doesn’t want to leave Grace, but she insists: “I think, Robert, that you had better go.”

And go he does, allowing Fredericks to use his favorite device, the divided storyline, following Robert on one hand and Grace on the other, because no sooner has he departed than he receives an urgent message from his old friend and boss M. Lefevere begging him to come to Paris to take over a difficult case.

Grace packs and heads for Paris, unaware that she will arrive there alone because Robert as taken a detour to New Jersey on one of his mysterious missions (like many sleuths of the era Robert is prone to omniscience when he isn’t dense as a teak two by four).

In Paris, Lefevere enlists Grace as his new assistant with typical Gallic resignation:

Immediately on reaching Paris, she drove to the office of the Prefect of Police, and sent in her card to Monsieur Lefevre. She thought it possible that he would expect her, as his agent in Washington would no doubt have communicated with him. Nor was she mistaken.

He rushed into the anteroom as soon as he received her card, and embraced her with true Gallic fervor, kissing her on both cheeks until she blushed. Then he drew her into his private office…

“But — it was for that very case that I desired his assistance. And by this Stapleton, who cables that the whole police force of Paris are a lot of jumping jacks! Sacre! It is insufferable!”

“You wanted my husband for the same case?”

“Assuredly! What else? The child of this pig of a millionaire is stolen — what you call — kidnapped! We have been unable to find the slightest clue. I am in despair… The efficiency of my office is questioned. My honor is at stake. I send for my friend Duvall, to assist me, and — sacre! — I find him already working for this man who has insulted me. It is monstrous!”

If you didn’t see this coming I have some lovely land in New Mexico I’d like to sell you — nice place called the White Sands Missile Testing Range …

So Grace goes undercover so she will not be recognized as the wife of the brilliant Robert Duvall. Fredericks, true to the nature of the pulps, conveniently fills us in on what Grace is up to:

On the day following that upon which she arrived in Paris, Grace Duvall sallied forth, determined to find out two things — first, the position occupied by Alphonse Valentin in the affair of the kidnapping; secondly, the identity of the man who had stolen the box of cigarettes from Valentin’s room, and gone with them to the house in the Avenue Kleber. The latter incident seemed trivial enough, at first sight; yet she reasoned that no one would risk arrest on the score of burglary, to steal anything of such trifling value, without an excellent reason.

Meanwhile (there are a lot of meanwhile’s in this series) Richard arrives in Paris not knowing Grace is already there and finds his work complicated by his old friend and a police agent he doesn’t realize is a disguised Grace:

“Good Lord, Chief, am I losing my senses? What is this affair, anyway, a joke?”

“Far from it, Monsieur Duvall. The criminals are still at large. The boy is in their hands. We must recover him.”

“But — this money– ”

“I arranged to get it, in order to prevent Monsieur Stapleton from making a fool of himself. I wish to capture these men — not to let them blackmail him out of half a million francs.” “Had you not interfered, Monsieur Lefevre, they would have been in my hands, by now. I would have had them safely the moment they attempted to enter Paris…”

Of course rather than simply explain the truth, everyone is as high handed and thick headed as possible without actually provoking the Dorothy Parker reflex (“This book should not be put aside lightly — it should be thrown with great force.”).

Robert may be “gifted,” but Grace is lucky. At one point she just walks into the kidnapper’s lair and finds the kidnapped child hidden in a plaster casting, then she herself spends a day hiding in a closet from which she luckily overhears all sort of vital information. All I ever heard in a closet was the sound of my clothes being devoured by hungry moths, but then I’m not a plucky sleuth.

Of course on their separate courses the Duvall’s manage to solve the case, rescue the kidnap victim, and capture the villains after a few close calls:

The semidarkness showed a terrifying spectacle. On the floor lay a woman, unconscious, clutching in her arms a child, trapped in a long gray coat. Down the dark hallway leading to the rear of the house dashed the figures of two men. One of them turned, as the attacking party entered, and hurled the lighted candle which he bore full into their faces. The entire scene was instantly plunged into darkness.

Golly!

But Robert brings it to a satisfying conclusion and explains all the convolutions of the case and how everyone but him was wrong, and M. Lefevere resolves that:

“The credit belongs equally to both. And that, my children, is as it should be. This affair, so happily terminated, has taught me one important lesson. It is this: The husband and the wife should never be in opposition to each other. They must work together always, not only in matters of this sort, but in all the affairs of life. I attempted a risky experiment in allowing these two dear friends of mine to attack this case from opposite sides. But for some very excellent strokes of luck, it might have resulted most unhappily for all concerned. Hereafter, should Monsieur Duvall and his wife serve me, it must be together, or not at all.”

You can hardly call these fair play detective stories. Indeed they are full of the sort of thing that the Detection Club and Van Dine’s famous rules were designed to correct, and yet despite prose as “bland as unsweetened farina,” and the high-handed hi-jinks of Robert Duvall, the books are fun and a pleasant read.

And as Robert Sampson points out, Grace Duvall is something refreshing, in that her adventures continue after marriage rather than finding her ensconced in the home like some princess locked away in a tower. For her day she was a breath of fresh air, however musty the plots she was involved in.

I enjoyed this and some of Fredericks other works (available on line at Manybooks and Google Books) on their own merits. Like most popular fiction of the age they require a bit of forgiveness by modern readers, but they also offer some genuine entertainment and polite well behaved thrills.

And historically Grace Duvall is the grande dame of all those bright nosy tec wives to come. She might be a bit staid and prim, but she is a true cousin of Nora Charles, Pam North, Halia Troy, Iris Duluth, Phyllis Shayne, Jean Abbott, Arab Blake, Helene Justus, and the whole attractive brood replete with wicked jaws, long elegant legs (hollow in the case of Nora and Pam), golden curls, and unerring taste for murder.

Though in all fairness after spending an evening with Robert you may well be wishing for one of Nora Charles and Pam North’s stronger martinis… Even as great detectives go, he really is a pain.

Gifted my …

Oh, well, see for yourself.