A REVIEW BY CURT J. EVANS:

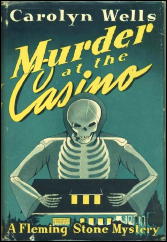

CAROLYN WELLS – Murder in the Casino. J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1941.

After reading The Gold Bag (1911, reviewed here ) and Feathers Left Around (1923, reviewed here ) — early and middle period Wells efforts respectively–I thought I would try a late one, Murder in the Casino. A casino setting might be interesting, I thought.

That was back in September 2009. Nearly a year later, I have finally forced myself to finish the book. Verily, dear readers, I hope the suffering I went through on your behalf with this one is appreciated.

What is Murder at the Casino about, you must be eagerly wondering. Well, one thing it is not about is a gambling casino (that might have threatened the merest modicum of excitement).

There is a murder at a sort of public entertainment hall for dances and this sort of building can be called a casino, but, for all the use Wells makes of the setting, the murder might have taken place at the opera, the bridge party, the flower show, et cetera — you would just have to take her word for it. This is probably the blandest mystery novel I have ever read.

To the extent this book is about anything, it is about lovely Rennie Loring. Or more exactly, Rennie’s eyes, to which Wells devotes the first chapter ( “Rennie’s Eyes”), as well as the last sentence of the tedious tale.

The author wants her readers to understand that the merest look from the intoxicating Rennie can conquer all men in her path. In short, Rennie is one of those tiresome Carolyn Wellsian child-women, ingenuously advanced in the art of coquetry but otherwise an absolute nitwit.

Wells had been perpetrating such characters since before World War One, but apparently her audience had an endless appetite for them, even on the eve of Pearl Harbor and the advent of Rosie the Riveter. So I suppose whether you like Murder at the Casino will depend a great deal on how much you like reading about idiot savant coquettes.

Renny’s brother and sister-in-law help get her married off to Nicholas Talbot, the richest man in the very rich suburban Connecticut community in which they live with Renny. Charming Renny throws over her old boyfriend to marry Mr. Moneybags. Unfortunately, Talbot proves to be a jealous tyrant.

As Wells interestingly puts it, Talbot had “a latent Othello complex, which it were wise not to monkey with.”

The couple take their honeymoon in Mexico City (though it could have been in their own backyard, for all the writing conveys of the atmosphere), and an inspired Renny, once back home, decides she wants to put on a Mexican dance at the local casino:

“Shall we have real Mexican girls and young men, or our own crowd, fixed up?” asks Renny. “Our own people, of course,” her husband declares. “We don’t want those brown folks around!” So the fun goes ahead, sans authentic “brown folks,” and with Renny dancing the lead female part and Talbot’s nephew the lead male part.

Describing this dance affair, Wells takes time, as was her wont, for a little fashion show commentary:

Renny’s costume … was a full red skirt with a green yoke, spangled all over, with a white silk low-cut blouse embroidered with beads of all colors … Steve Trask as the charro, was gorgeous in long, tight leather trousers, covered with silver buttons and chains, a soft leather jacket, braided in silver and gold, and a gorgeous serape.

If this were Agatha Christie, there would be something sinister about that serape, but, unfortunately this is Wells, and she is much more interested in pure fashion than murder, so what you see is all you get. Though a murder finally does take place, during the dance, when Rennie’s husband –surprise! — is stabbed to death.

For the rest of the book the wealthy locals emphasize that the foul deed must be the work of the radicalized lower classes (Emma Lazarus, what hath though wrought?!):

“Must have been…some disgruntled Communist who resented Nick’s wealth.”

“I suppose it must have been some of those bad men who hate rich people. You know what I mean, Reds, they call them, I think.” (Yes, this is Rennie.)

“You think, then, Rudd, that it was some laborer or workman?”

“I think the wicked man who who killed Steve was the same sort of man that killed my husband. Those bad people who make strikes and things.” (Yup, Rennie again, this time after a second dastardly murder.)

It would be pleasant to believe this is intended as social satire, but as Wells gives every indication that she greatly admires the stupid people of this wealthy suburban Connecticut town ( “a restricted residential district”), I think she is serious. You would honestly think it was 1886 and that the Haymarket Riot had just occurred.

Much of the dialogue in this tale (and the tale is mostly dialogue) is written as if the author’s first language were not English:

â— “Then I’ll give my advice to you… Put a little more dignity into your own performance, and curb your tendency to amorous gestures and tones. They are uncalled for and they greatly mar the picture.”

â— “It is hard to be sure, but I think Mr. Talbot believed the beneficent inscription, and that later, only yesterday, in fact, he learned the true translation, and that being attacked, he tried to get the ring off, and did so, but it was too late, and he dropped the ring under him, where it was later found by the detectives.”

â— “Yet the conditions are simple. Renny Loring and I have been in love for years. Along comes Talbot, and gets her away from me by reason of his great wealth and position and general attractive qualities.”

â— “I am an astronomer, Inspector, and on occasion I view the Heavens to see what the planets are up to now. The great windows in these halls offer fine views to a student of astronomy, and I enjoy them greatly.”

Wells’ greatest Great Detective, Fleming Stone, shows up and solves the case, though no discernible process of ratiocination that I could detect. Rather, Stone simply announces he knows who the killer is and the killer promptly confesses and kills him/herself with yet another one of those convenient poison pellets one finds so much in Golden Age tales, particularly those penned by Carolyn Wells.

Talk about dumb! This person must have been even dumber than Renny.

The entrancing and filthy rich Renny, by the way, does not the know the meaning of “berserk” or “privileged communications” and says “electricated” when she means “electrocuted.” Surely this helps explain why there is no chapter in Murder at the Casino entitled “Rennie’s Brain.” It would have had to have been a very short chapter indeed.

Murder at the Casino was apparently Wells’ seventy-ninth mystery tale (I cannot bring myself to call them detective novels). Two more Wells mysteries would be published after Casino in 1942 (one I believe posthumously).

My copy of Casino, published by Lippincott, a major publisher, is a very attractive volume: well-bound, good creamy paper, an excellent dust jacket. Lippincott must have known what it was doing publishing these later Wells books, but I cannot fathom why people enjoyed reading them. My only guess is that they were 1941’s version of “cozies,” but that guess it sort of insulting to many modern day cozy writers.

Perhaps the best comparison might be with the books Lilian Jackson Braun was writing in her nineties, before her publisher, Putnam, finally dropped the series in 2007. However classically “alternative” (to borrow a term from Bill Pronzini’s Gun in Cheek) Wells’ earlier mysteries may be, they cannot match Murder at the Casino for sheer inept daftness.