SELECTED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

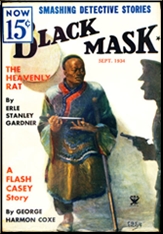

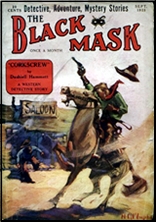

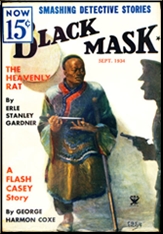

ERLE STANLEY GARDNER “The Heavenly Rat.” Novella. Ed Jenkins (a/k/a the Phantom Crook). First published in Black Mask, September 1934. Not known to have been collected or reprinted.

I felt certain that the police, for all they wanted me, would never recognize me as the shabby figure that prowled around Chinatown — the figure of a white hanger-onner who had been crowded out of the society of his own kind and into the dark poverty that fringes Chinatown.

After Perry Mason and Donald Lam and Bertha Cool, the most popular of his creations, and certainly of his many pulp characters, was criminal Ed Jenkins, the Phantom Crook who haunted the pages of the legendary Black Mask.

Jenkins is a professional crook always in the shadows, often in disguise, and often hiding among his friends, allies, and sometimes rivals in the shadows of Chinatown. Gardner, who had begun his career as a young lawyer in Chinatown representing clients there, had a genuine interest and respect for the people, and if there is the faintest taint of condescension and prejudice still found in stories like this one they were, for their time, fairly rare in their representation in the pulps of the Chinese as human beings and not the Yellow Peril, as allies and not implacable cruelty personified.

In “The Heavenly Rat†Jenkins, in disguise as a down-on-his-luck bum looking for work, is stopped by a man who flashes a badge and tell him if he wants work to meet him that night at the “Yellow Lotus.†Once the man is gone, Jenkins really has no reason to show up, but there is something about the fellow, he’s no ordinary cop for one thing, that leads Ed to follow through.

Granted that might seem a pretty odd thing for a wanted man to do, but then Jenkins is a somewhat more grounded and less romantic version of the Saint in many stories. He just can’t not show up especially when he is tipped to “a twist in a blue coupe†tagging him after the man with the gold badge approached him.

The girl is Beatrice Harris, the daughter of miner George Harris, accused of murdering his ex partner Frank Trasker after a strike. Also partners in the game were an ex pug named Sam Reece, and a Chinese cook. The big shot behind them, the man who flashed a badge and hired Jenkins, is Oscar Milen, and he knows who killed Trasker, that’s why Harris daughter is following Ed hoping if she does Milen’s bidding he will clear her father.

The game ups considerably when Jenkins witnesses Sam Reece killed by a big one legged Chinese on a crutch with a throwing knife in the fog. As Reece dies he lets two words escape his lips, T’sien Sheuh, “the Rat of Heaven†aka “the Bat.â€

The story has pretty much everything, a good girl in with bad men trying to clear her Father, if indeed he is innocent, a smart dangerous criminal the police can’t or won’t touch, a hero with no one to call on for help caught between protecting his neck and helping a girl he can’t trust, and a mysterious Chinese exacting revenge in the San Francisco fog.

And Gardner rings every change out of those old familiar bells, never letting his hero or his readers pause, spinning expertly from one moment to the next, the writing not as artful as Hammett, Chandler, or Whitfield, but never less than perfectly expressed.

I slid the car with its gruesome burden into the dark shadows of a particular alley, and thanked my lucky stars that the night was so foggy. Thick fog had settled down like a gray blanket, enveloping the streets in white mystery, muffling the sounds of night life on the pavement.

Hammett would have said it cleaner and sharper, Chandler more eloquently, but Gardner nails it without fuss or bother. There is something to be said for cool professionalism.

Tongs, revenge, a big dope deal, a beautiful girl, Jenkins framed for Sam Reece death, it all piles on in a novella that moves in a clip down to a satisfying conclusion of that favorite Gardner plot, the Cinderella story, with Jenkins on his own again as he always is.

No more of the city underworld for her. She was going back to windswept silences, the clean dry air of Nevada.

As for me, I had cast my lot in life. I was headed back toward the only life that I could live — the foggy, mysterious streets of San Francisco’s Chinatown — the underworld …

Maybe the music is a little tinny, the tune a bit too familiar. Like the ever present fog a familiar slightly musty air lays over it all, but it is still music, still sweet, still beautiful in it’s oft repeated rhythms if you know how to listen, and are inclined to its song.