Thu 11 Feb 2021

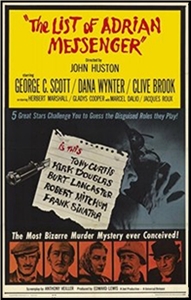

A Book! Movie!! Review by David Vineyard: PHILIP MacDONALD – The List of Adrian Messenger // Film (1963).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[17] Comments

PHILIP MacDONALD – The List of Adrian Messenger. Col. Anthony Gethryn #12. Doubleday, US, hardcover, 1959. Bantam A2186, US, paperback, 1961; #F2643, 1963. Herbert Jenkins, UK, hardcover, 1960.

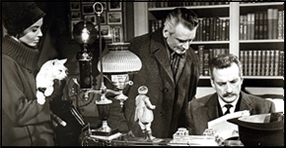

THE LIST OF ADRIAN MESSENGER. Universal-International, 1963. Kirk Douglas, George C. Scott, Dana Wynter, Jacques Roux, Herbert Marshall, Clive Brook, Gladys Cooper Guest Stars: Tony Curtis, Burt Lancaster, Frank Sinatra, Robert Mitchum. Screenplay by Anthony Veiller. Directed by John Huston. Available on DVD.

When writer Adrian Messenger asks a friend to use his influence to look into a disparate list of men from all walks of life and all parts of the United Kingdom it seems like nothing but a whim, but shortly after, when Messenger is killed in a plane crash the friend in question turns to Anthony Gethryn to look into the list, almost immediately one fact arises, all ten men died of untimely accidents, including Adrian Messenger, making for a strangely coincidental eleven accidental deaths seemingly unrelated deaths.

Semi-amateur sleuth Col.Anthony Gethryn (The Rasp, Warrant for X) suspects something, and with the help of one of the survivors, a Frenchman, Raoul St. Denis, who coincidentally was once a member of the French Resistance run by Gethryn anonymously in the war, it soon becomes apparent Adrian Messenger was onto something sinister and deadly.

At first Gethryn’s friend at the Yard, Lucas, and his old ally Inspector Pike, think Anthony is jumping at conclusions, but between a dying message left by Messenger in the lifeboat with St. Denis, and an expanding investigation it becomes clear there is a killer on the loose, one who has carefully over the years eliminated anyone who might know him for an as yet unknown reason.

A series, if not serial, killer who eventually tallies sixty seven murders over much of the globe, all disguised as accidents, a criminal genius who only has two more deaths to go, an old man and a fourteen year old boy, the Marquis of Gleneyre and his grandson, heirs to a considerable fortune.

Worse, there may be nothing the law can do to stop him.

The List of Adrian Messenger is the final novel in the Anthony Gethryn series that began at the height of the Golden Age of the Detective Novel from a writer whose books such as The Rasp, Warrant for X, Escape, Mystery of the Dead Police (X vs Rex), and Patrol led him to Hollywood and a long career as a screenwriter penning everything from Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto to Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca.

It is not the end of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction; writers such as Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh, John Dickson Carr, and John Rhode, not to mention Ellery Queen and Rex Stout in this country, continued to write for sometime after MacDonald’s death. Still it is coda to the era, and works both as a fair play mystery novel, and not unusual for MacDonald, as a suspense novel and a thriller, making it a compellingly readable mix of the old and the new.

Series killers, even serial killers, weren’t new to the Classical Detective story. Christie’s The Alphabet Murders, Conan Doyle’s Sign of the Four and A Study in Scarlet, MacDonald’s own Mystery of the Dead Police and Murder Gone Mad and the plot here has some interesting ties to MacDonald’s plot for his original screenplay for Circle of Danger in the motive for the killer.

What interests me here is where the 1959 novel and the fine 1963 film by John Huston vary, because while the Huston film uses large chunks of dialogue directly from the novel it varies importantly from the book on one key point, one that puts Anthony Gethryn in the mainstream of the high handed Great Detective model and ironically sets him against the entire genre.

So at this point:

Spoiler Warning!

Spoiler Warning!

Spoiler Warning!

One of the key personality traits of the Great Detective has always been his high handed behavior, hiding key facts from his Watson, playing God (almost all the Ellery Queen novels after The Door Between are concerned with Ellery’s unease playing God in his role as Great Detective), and acting as a figure of justice and vengeance and not merely law. When Sherlock Holmes at the end of “The Speckled Band†mused he wasn’t much bothered by the fact his actions led to the death of the brutal doctor Conan Doyle could hardly have imagined how many writers would take it to heart.

Philo Vance practically encouraged the murderers he caught to commit suicide. Even Charlie Chan saw quite a few of his killers dying by their own hand rather than waiting for a messy trial and even Agatha Christie’s seemingly cozy Miss Jane Marple defined herself as Nemesis and not merely a puzzle solver. John Dickson Carr’s Dr. Gideon Fell burns down a house to keep the police from charging a murderer in The Man Who Could Not Shudder to avoid a miscarriage of justice.

But few act as decisively as Anthony Gethryn does here.

In the film, as in the book, the killer, George Brougham (Kirk Douglas), is known about half way through the book, but he has left no trail. The police have nothing but suspicions, and short of catching him in the act, and nothing suggests he will be that stupid, he only needs to wait patiently to kill the fourteen year old heir who simply cannot be watched for the rest of his life.

Knowing that Anthony Gethryn (George C. Scott) deliberately lets Brougham know that he is close to uncovering his secrets and forces him to try to kill Gethryn, the attempt, and Brougham’s fate sealed at a fox hunt (which plays a large part in film and book though more so in the film because director Huston was devoted to riding to the hounds on his Irish estate) Brougham meeting a satisfyingly grim justice impaled on a farm implement he meant to use to kill Gethryn.

At which point the film pauses to show us the clever make up disguises used by Douglas and his four major guest stars.

And this is where the movie lets down fans of the book somewhat, because the ending of the book is considerably more stunning, Gethryn telling Lucas after he has seemingly walked away from the case.

Gethryn doesn’t just set a trap to capture Brougham, though he does use the young Marquis as bait to catch Brougham in the act, he knows that short of allowing Brougham to kill the boy in front of witnesses the law has almost no case, so Gethryn, St. Denis, members of the French resistance, Hispanic allies and friends of Gethryn, and the Marquis and Adrian Messenger’s cousin Jocelyn (Dana Wynter in the film) lure George Brougham to California and arrange for him to be hoist on his own petard, to die in an accident while fleeing a foiled attempt to kill the boy.

In short they conspire to and successfully execute George Brougham, by “accident,†or as St. Denis notes in the books final line, “What you would call, I think, a justice poetic…â€

I think it is that ending that gives the novel a unique place in the history of the Golden Age of the Fair Play Detective novel. The world has changed, and murder is no longer committed by gentlemen who can be expected to conveniently put a bullet in their own brain rather than face trial, imprisonment, and shame.

George Brougham has no shame. He is a modern killer, amoral, a sociopath, a cunning murderer willing to kill dozens to achieve his goal. He is evil, but a more mundane and frightening kind of evil than a Fu Manchu or a Moriarty. He is a human monster born out of WW II, ruthless, clever, and above the ability of the law to stop him.

The oh so civilized rules of the Golden Age Detective Novel have broken down and no longer apply, it is no longer just a game. The victims are ordinary men and potentially a boy who has harmed no one. The killer is as amoral and efficient as the monsters who marched millions into ovens to die in death camps, and his motive isn’t political, it’s money and power.

To defeat him, Anthony Gethryn has to forgo the academic and cool analytic of the Great Detective he becomes an avenger as much as a Bulldog Drummond, James Bond, or Mike Hammer, an agent of chaos and not order, the classical role of the Great Detective.

Hercule Poirot will find himself in the same role in his final adventure, Curtain. It is a concession of the Golden Age to the modern world. The brain and the intellect is not enough in the face of evil, the dragon must be met on his own level. Which at least, for me, makes The List of Adrian Messenger a fairly revolutionary statement from one of the masters of the Golden Age puzzle.

Murder is no longer a game and its victims no longer pawns. That idea that real people are dying and murderers walk among us is almost more than the fragile conceit of the Golden Age can bear.

I think a fairly good argument can be made MacDonald was putting the audience and his fellow writers on notice that the cozy comfortable world they created was no longer enough for readers and no longer sustainable as mystery fiction. You have to wonder whether he would have carried Gethryn beyond this point if he had lived longer, or if he had said all that could be said about the Great Detective from his point of view.