Wed 25 Jan 2012

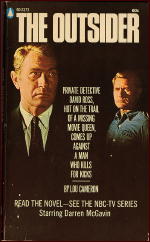

A TV Movie Review by Michael Shonk: THE OUTSIDER (1967).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , TV mysteries[22] Comments

THE OUTSIDER. Made for TV “World Premiere” movie. NBC-TV/Huggins-Universal Productions, 21 November 1967. Cast: Darren McGavin as David Ross, Edmund O’Brien as Marvin Bishop, Sean Garrison as Collin Kenniston III, Shirley Knight as Peggy, Nancy Malone as Honora, Ann Sothern as Mrs. Kozzek, Joseph Wiseman as Ernest, Ossie Davis as Lt. Wagner. Music: Pete Rugolo. Director of Photography: Bud Thackery. Written and Produced by Roy Huggins. Directed by Michael Ritchie.

The Outsider is a story suitable for Black Mask magazine, a noirish tale of a loser PI on a simple case that spins out of control with a lying client, violence, betrayal, drugs, seedy L.A. music club life, a femme fatale, and doomed characters.

The story opens (as will the later series episodes) with David Ross narrating over an action scene that takes place later in the story. Ross is in a car driven off a cliff. He survives and the narration says, “My name is David Ross, and you may be wondering how I got into a situation like this.â€

Flashback to the beginning. Rich business manager Marvin Bishop hires PI David Ross to find out if one of his employees, Carol is stealing from him.

After spending the night trailing Carol, Ross is woken early by his client. Bishop is less than impressed by Ross. But Ross makes no apologies for his rundown apartment, that he is broke, never finished high school, has no office or secretary, and drives an old car.

He tells Bishop about trailing Carol to a jazz club where she met her boyfriend Collin. Collin has no past beyond a few years ago when the cops caught him shaking down homosexuals.

That night Ross walks into a trap. Collin uses a garrote on him and tries to learn why Ross is tailing them. Carol panics, spoils the trap, and the two run. Shortly after, Ross finds Carol dead in her bedroom. After he calls the cops, the phone rings, it is Collin.

Ross picks up his rich girlfriend Honora, an expert in L.A. club scene. Honora knows Ross will never marry, that would mean joining the world and Ross will always be an outsider. They search for Collin and find him at a Rock music club. Ross and Collin fight. Ross leaves the unconscious Collin for the cops and heads to question his client.

Bishop is unhappily married, and was having an affair with Carol. He had really hired Ross to learn if she was cheating on him. Bishop claims he did not kill Carol.

Cops question Ross. Collin has an alibi. The cops then discover Ross had served six years in prison for killing a man. Ross explains he was 19 and riding freight trains when a yard bull caught him and started to beat him with a nightstick. Ross hit him once killing the man. He had received a full pardon.

Ross has no idea what Collin is up to or who killed Carol. But Collin is equally curious about Ross. Ross finds Collin while Collin and the femme fatale are in the middle of an LSD trip supervised by Ernest the drug guru while Collin’s Mom watches TV game shows. But once available, Collin refuses to answer Ross’ questions.

Frustrated, Ross returns home. Bishop arrives and tells Ross to drop the case. Ross refuses. Bishop leaves and is shot at the bottom of the stairs.

The cops question Ross, but after a phone call, let him go.

Ross returns home knowing Collin is waiting inside, when Ross outsmarts Collin, the femme fatale knocks Ross out from behind. They think he is dying and panic. They take him to the cliff for the scene from the opening as they send Ross and car over the cliff.

There is a short gunfight. Ross then drives away with the femme fatale. He promises to help her escape if she tells him everything. She does. What she and Collin were doing had nothing to do with Carol’s murder and Bishop’s shooting. Ross hears on the car radio the cops have caught the killer. Ross takes the femme fatale to the cops. She reminds him of his promise to let her go. To which he happily replied, “I lied.â€

Roy Huggins (Maverick, Run for Your Life) was at his best here as writer and producer. His dialog was as hardboiled as Philip Marlowe and the handling of the club scenes and drug use was less melodramatic than usual for TV. The Outsider also featured many examples of Huggins odd humor, such as Ross keeping his telephone in the refrigerator.

Director Michael Ritchie (Prime Cut, Fletch) captured the noir style with a mix of 60’s b&w psychedelic style. He was nominated for a DGA award for this TV Movie.

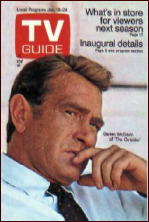

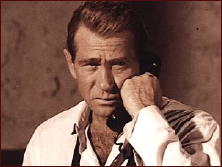

Darren McGavin (Mike Hammer, Kolchak: The Night Stalker) carried this movie as the admirable loser PI David Ross, a character without ego and comfortable with his limitations.

The Outsider TV Movie was part of an experiment by Universal and NBC looking for better ways to find TV series. Universal’s “World Premiere†movies were a test for the 100-minute (plus commercials and stuff) format as a pilot. It resulted in three new series for NBC’s 1968 fall schedule, Dragnet 1967, Ironside, and The Outsider.

In the book TV Creators: Conversations with America’s Top Producers of Television Drama by James L. Longworth (Syracuse University Press, 2002), Huggins discussed why he refused to be involved with The Outsider TV series:

The “shit†factor was most likely the growing concern over violence on television. Huggins was wise to avoid the headaches that Gene Levitt would experience when he produced The Outsider series.

Next time, we will examine The Outsider TV series.