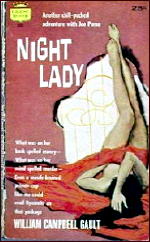

WILLIAM CAMPBELL GAULT – Night Lady. Crest 260, paperback original, 1958. T.V.Boardman, UK, hardcover, American Bloodhound Mystery #307, 1960. Never reprinted in the US.

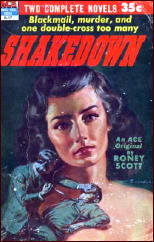

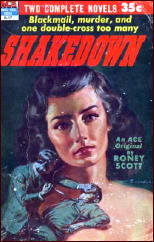

William Campbell Gault got his start writing for the pulp magazines, beginning around 1940, maybe earlier, producing not only mystery stories and crime fiction, but doing a slew of sports stories as well. When the pulps faded away and paperbacks came along, he, as did many others, went with the flow. His first Joe Puma novel, Shakedown, was written under the name of Roney Scott as half an Ace Double in 1953.

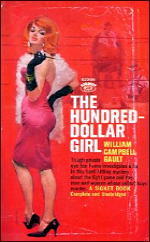

Then after a short hiatus came five Puma adventures in three years from Crest, then a hardcover novel, The Hundred-Dollar Girl, from Dutton in 1961. Gault switched to writing boys’ adventure fiction after that, and Joe Puma disappeared until The Cana Diversion was published in 1980 – about which more in a moment.

In many ways Joe Puma is your standard medium-boiled kind of private eye. His bailiwick is Los Angeles and immediate environs, mostly the seedier side of town, mixing it up with former small-time hoods, chiselers, grifters and big-time mobsters, along with a wide assortment of women. Night Lady is Puma’s third appearance, and while I can recommend it to almost any devout fan of private eye fiction, I have some serious reservations about it, and it’s highly unlikely that any publisher would consider reprinting it today.

I may totally wrong about this, but in terms of his writing, Gault seems to have been somewhat of a maverick, refusing to go along with the conventional, and veering off on occasion into strange, unusual ground.

Take the following excerpt from the first couple of paragraphs from Night Lady, as a mild example. As any good pulp writer should know, the first few lines are the most crucial in sucking the reader into the story. They have to be good, clear, and picturesque. Not this time. Here’s Gault’s take on professional wrestling and the wrestlers themselves:

It’s a trade that appeal [sic] to the narcissist. And from self-admiration it’s only a step to love of like for like.

And love of like for like can lead a man into something as socially responsible as Rotary or something as socially repugnant as homosexuality.

What is “love of like for like� It stumped me the first time I read it, and the second and third time, too. The words were there, but they didn’t make sense.

You’re probably way ahead of me in knowing what Gault was saying, but to me, it was like running a race with hurdles, and suddenly the hurdles are too close together, you trip, and you knock down the next one, and suddenly you’re cartwheeling down the track, arms and legs swinging out in all different directions, thud, thud, thud – and it stopped me cold.

And at the least, I wasn’t expecting this particular variety of deeply felt philosophy (page 23) to be expressed so abruptly and succinctly, not in the first paragraph. It caught me by surprise. I wasn’t an English major in college, and I avoided all of the English courses that I could, so don’t give me a letter grade on any of what I’m saying, but in any case, I think I flunked the first page.

You’ve also noticed the reference to homosexuality. In terms of either political correctness or just plain good taste, there are some references to gays in this book that probably would cause some fuss if they appeared in most fiction today: lavender lads (page 9), weirdies (page 11), a pansy bed (page 14), homo (page 29) and the old stand-by, queer (page 49). The word “gay†itself is not used.

Sometimes it’s Puma talking, sometimes it’s the people he’s talking to, without any particular rancor, other than the choice of words, but they’re there and they can’t be ignored. Someone else will have to finish this doctoral dissertation from this observation onward, however, not me.

You’re still waiting for me to say more about The Cana Diversion, perhaps. I haven’t forgotten, but let me first take care of those people who want to know more about the case Puma is working on in this book. He’s hired by a successful show-business wrestler named Adonis Devine to find his business manager, who’s been missing for two days. The business manager, male, also lives with Adonis, which means calling in the police may cause some problems.

When the missing man is found dead, the police do have to be called in, but since Puma does his best to stay on the good side of the law, he not only manages to keep a lid on things best kept hushed up, but he’s allowed to keep working on the case.

Which he does, and not only that, he obtains a new client, a rich girl who Puma thinks is seriously slumming, given her previous relationship to the dead man, his connection with the crooked (well, fake) wrestling entertainment business, and his “double-gaited†life style.

There is another girl involved as well, an eye witness to the killer’s departure, who is nice and who naturally needs Joe Puma’s protection. He’s kind of prickly about it, though. He’s a very class-conscious sort of individual. The women in this case, especially his new client and her friends, are high class group of people. Joe is lower middle class, and he quietly resents it. There is a chip on his shoulder throughout the book, not a nasty one, but a noticeable one.

Unusual. It gives the story some oomph that lesser accomplished private eye writers wouldn’t include, an edge that Gault has that other authors don’t. As for the mystery itself, Puma does a lot of detective work, but on page 128, with less than 30 to go, he himself has to admit that he has no more leads to follow or suspects to interrogate.

Then with some inspired guesswork and a curious slip on the part of the killer – there’s little the armchair detective at home could do to contribute – the case is solved, with still almost ten pages to go.

More of Gault’s maverick writing nature at work. Instead of cleaning up the loose ends, as he easily could have, Puma takes the time instead to fight a grudge match with his original client, Adonis Devine, the wrestler. Over five pages worth.

He also ends up in bed, just before that, with one of the two women in the case. I leave it to you to decide which one, or read the book for yourself. Given the caveats I’ve already expressed, Gault was a writer who always had something to say, and here as well, he’s definitely worth reading.

Now. If you’ve never read The Cana Diversion, and you think you might want to, you might also want to stop here. It’s common knowledge, though, so it’s not as though I’m releasing the Pentagon papers.

Gault’s other private eye detective was Brock “The Rock†Callahan, and when Gault starting writing mysteries again in the 1980s, he brought them together in the same book, The Cana Diversion.

Unfortunately, what he did was make Puma the murder victim, leaving Callahan the task of tracking down his killer. No other author has ever done this, before or since. I don’t know about you, but the idea has always seemed awfully creepy to me, and I’ve never read the book. (That’s a purely personal reaction, and if I were to try to explain further, it would probably tell you more about me than either you or I would want to know.)

And I realize, of course, that this leaves me open to widescale expressions of surprise and disdain, if not derison and dismay. In 1983 The Cana Diversion did nothing less than win the Private Eye Writers of America award for the Best Paperback Original of the Year. Sometimes it pays to go your own way.

Note: Thanks to Bill Crider, Richard Moore and Bill Pronzini for some insightful commentary they made on some preliminary versions of this review. The opinions as expressed above, however, remain as always, mine alone.